Economy

From Dubai To Delaware: The Shift In India’s Migrant Money, Explained Here

Amit Mishra

Apr 02, 2025, 12:58 PM | Updated Jun 02, 2025, 11:34 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

The bulk of India's remittances (by value) are now coming from places like the Silicon Valley and New York and London finance centres. This is a change from previous situation where the blue-collared workers in Gulf economies sent the majority of remittance into India.

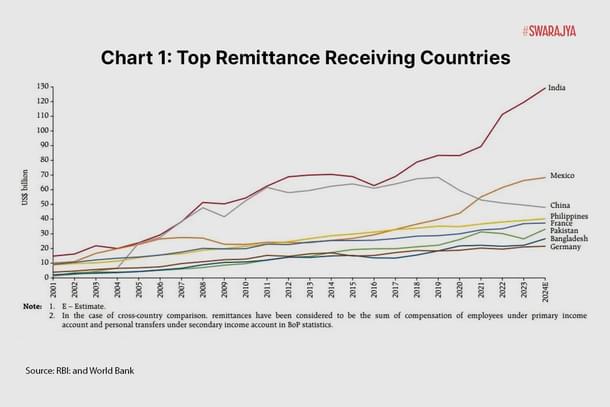

For over a decade, remittances have outpaced foreign direct investment (FDI) in India, proving to be India’s most reliable financial lifeline. In 2023-24 alone, the country received a staggering $118.7 billion in remittances—more than double the $55.6 billion recorded in 2010-11.

When migrants send home part of their earnings in the form of either cash or goods to support their families, these transfers are known as workers’ or migrant remittances. They have been growing rapidly in the past few years and now represent the largest source of foreign income for many developing countries.

What makes remittances truly extraordinary is their resilience. Unlike capital flows, which fluctuate with market conditions, remittance inflows remain steady—even rising during times of crisis. In economic downturns or in the aftermath of natural disasters, when private investments retreat, remittances surge, offering a crucial safety net for millions.

Dubai To Delaware

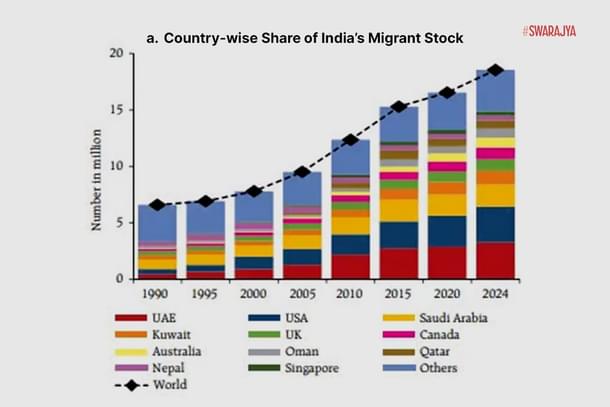

India’s stock of international migrants has tripled from 6.6 million in 1990 to 18.5 million in 2024, with its share in global migrants rising from 4.3 per cent to over 6 per cent during the same period.

While India will likely continue to supply talent to the world for years to come, the nature of its emigrant workforce is undergoing a significant transformation.

Contrary to popular culture narratives, Indian migration was primarily associated with low-skilled, informal employment in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries. Today, however, a significant structural shift is underway, with Indian professionals increasingly securing high-skilled jobs in high-income nations such as the U.S., the U.K., and East Asia—including Singapore, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand.

The latest findings from the Reserve Bank of India’s sixth remittances survey (2023-24) confirm this shift - the share of advanced economies in India’s inward remittances has risen, surpassing the share of Gulf economies, reflecting a shift in migration pattern towards skilled Indian diaspora.

The United States has now emerged as the largest source of remittances to India, contributing a substantial 27.7 per cent of total inflows in 2023-24, while the United Arab Emirates (UAE) follows at 19.2 per cent. This marks a significant reversal from the 2016-17 survey, when the UAE held the top spot with a 26.9 per cent share, and the U.S. ranked second at 22.9 per cent.

In 2023-24, the combined contributions from the U.S., the U.K., Singapore, Canada, and Australia accounted for more than half of India’s remittance inflows. Meanwhile, the GCC nations—UAE, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Qatar, Oman, and Bahrain—saw their collective share decline to 37.9 per cent, down from 46.7 per cent in 2016-17.

Decoding the Shift

This shift isn’t just happenstance.

One key driver of this change is the rise in the share of Indian professionals securing high-paying jobs in the U.S. and the U.K. According to the RBI, about 78 per cent of Indian migrants in the U.S. are employed in high-earning sectors such as management, business, science, and the arts. Their growing presence in these industries has significantly boosted remittance inflows from these nations.

At the same time, the increasing preference for Canada, the U.K., and Australia as study destinations has played a crucial role in this remittance surge.

As of January 2024, a staggering 13.4 lakh Indian students were studying abroad, with Canada hosting the largest share (32 per cent), followed by the U.S. (25.3 per cent), the U.K. (13.9 per cent), and Australia (9.2 per cent). The financial support these students receive from home and the eventual transition of many into high-paying jobs abroad have further strengthened remittance inflows.

"Following the competitive edge and the penetration of Indian IT services overseas at the start of the century, the number of skilled emigrants to advanced economies (AEs), especially to the US, has risen significantly. Thus, besides GCC countries, AEs have also emerged as a major source of inward remittances to India over the years, reflecting the changing dynamics of India’s diaspora, the RBI said in its report.

Some of this is also a function of active policy interventions. Take, for example, the India-U.K. ‘Migration and Mobility Partnership’ signed in 2021.

In just three years, the number of Indians migrating to the U.K. tripled—from 76,000 annually in 2020 to 250,000 by the end of 2023. This surge has left a clear imprint on remittance inflows, with the U.K.'s share rising from 6.8 per cent in 2020-21 to 10.8 per cent in 2023-24.

At the same time, while the shift towards advanced economies is evident, it’s important to note that the Gulf is far from losing its significance.

The region still accounts for 38 per cent of India’s total remittances, with the UAE alone contributing 19.2 per cent. In absolute numbers, the Gulf continues to employ more Indian workers than any other region. However, in dollar terms, its dominance is beginning to wane.

Why is this shift important? Because the type of jobs that Indian emigrants take abroad directly impacts the volume of remittances. A single software engineer in Silicon Valley or an investment banker in London can send home as much as ten construction workers in the Gulf.

Unlike remittances from the Gulf—which are more vulnerable to fluctuations in oil prices, migration policies, and economic downturns—those from advanced economies tend to be more stable. A stark example of this was observed during the COVID-19 pandemic: while remittances from the Gulf dipped sharply, those from the U.S., the U.K., and other advanced nations remained steady.

For instance, remittances from the UAE saw a significant drop of 8 percentage points during the pandemic, falling from 26.9 per cent in 2016-17 to just 18 per cent in 2020-21. Meanwhile, remittances from the U.S. rose slightly, increasing from 22.9 per cent to 23.4 per cent over the same period.

The Ubiquitous-But-Silent Problem

Despite remittances being a lifeline for India's economy, a significant portion—billions of dollars—is lost to high transaction fess.

Sending money home should be much more affordable, yet it remains surprisingly costly. The UN's Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) have set an ambitious target to reduce the cost of sending $200 to 3 per cent or less by 2030, but progress has been slow.

The global average cost of sending $200 has dropped over time, from 9.67 per cent in 2009 to 6.65 per cent in 2024. However, this still exceeds both the initial G20 target of 5 per cent and the SDG goal.

For India, the situation is somewhat better. With a 4.9 per cent cost of sending US$ 200 in 2023, the cost of sending remittances to India is not only below the world average cost, but has also met the initial G20 target reflecting the changing dynamics of cross-border money transfers.

The cost of a remittance transaction includes two elements – the fees charged at any stage of the transaction and the exchange rate conversion from the sender's local currency to the recipient's currency.

Since inward remittances are largely used for family maintenance, these costs have a significant socio-economic impact, making the reduction of remittance fess a crucial policy agenda globally.

For large remittances—those linked to trade, investment, or aid—transaction costs are not usually an issue. This is because as a percentage of the principal amount, they tend to be small, and major international banks tend to offer competitive rates for these larger sums.

However, for smaller remittances, often under $200 (a common amount for lower-income migrants), fees can range from 10 per cent to as high as 15-20 per cent of the total transfer, particularly in smaller migration corridors. It’s the poorest migrants, who most urgently need their funds, who end up losing the most to processing fees.

Why so?

The method and platform used to send money home makes a world of difference. Transfers via traditional banking channels, such as the SWIFT system, can incur hefty fees—sometimes as high as 11.9 per cent for smaller transfers. In contrast, newer fintech-driven remittance services, such as those using India’s Rupee Drawing Arrangement (RDA), offer significantly cheaper rates, with costs as low as 1 per cent for large transfers.

The lesson for India here is to double down on digital infrastructure. India has been at the forefront of the efforts to enhance cross-border payments by collaborating bilaterally with various countries to link its Fast Payments System (FPS) – UPI, with their respective FPSs for cross-border Person to Person (P2P) and Person to Merchant (P2M) payments.

For example, the UPI-PayNow linkage is a pertinent example of how Singapore and India have leveraged the open banking APIs to allow account holders of participating financial institutions in the respective countries to conduct seamless transactions using their individual FPSs.

In July 2024, the Reserve Bank of India joined “Project Nexus”, which facilitates multilateral FPS linkages among four ASEAN countries—Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand.

In over 70 countries today domestic payments reach their destination in seconds at near-zero cost to the sender or recipient. This is thanks to the growing availability of instant payment systems (IPS). Connecting these IPS to each other can enable cross-border payments from sender to recipient within 60 seconds (in most cases).

Nexus is designed to standardise the way that IPS connect to each other. Rather than a payment system operator building custom connections for every new country that it connects to, the operator can make one connection to the Nexus platform.

As digital adoption grows, we can expect remittance costs to fall, benefitting millions of Indian families. However, the real challenge lies in ensuring that the benefits of this digital revolution extend to smaller, everyday transactions, allowing even the most modest remittances to reach their recipients without excessive fees.

The Bottom Line

What India's remittance story also reveals is that while China is synonymous with exporting goods, India is increasingly recognised for exporting talent. And within this talent pool, the value added and remittances sent home by knowledge-based professionals are increasingly outpacing those sent by blue-collar workers.

However, this shift comes with its own challenges. While remittances provide essential financial stability, they cannot be a long-term solution to achieving economic self-sufficiency. While remittances can spur long-term growth by increasing savings and investment in the home economy, there is also the risk of the labour market at home suffering a shortage of skilled workforce if all skilled resources leave for foreign shores. Over and above this, a reliance on remittances implies that the Indian economy and millions of Indian households are dangerously vulnerable to events beyond Indian shores.

The fact that remittances fund 42 per cent of India’s trade deficit is both reassuring and troubling—it brings stability, but also highlights India's growing dependence on this income stream.

Even so, they are a critical component of the Indian economic engine, and the findings of the RBI's latest report only show that remittances are set to give an even greater thrust to the machine.