Economy

India, America And Energy

Venu Gopal Narayanan

May 28, 2023, 04:50 PM | Updated 04:50 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi will be visiting America next month. The high point is a banquet which will be thrown in his honour by his host, President Joe Biden.

The rush for banquet tickets is apparently so heavy that Biden complained about it to Modi when they met at Hiroshima, Japan, last week.

“You are causing me a real problem…Everyone in the whole country wants to come. I have run out of tickets... Everyone from movie stars to relatives. You are too popular", Biden grumbled good-naturedly.

Yet, the truth is that the most important aspect of Modi’s trip will be intense negotiations on energy, defence and regional security. Multiple meetings at the highest levels have already been conducted over the past few months, and more are planned.

Lloyd Austin, America’s Defence Secretary, is visiting New Delhi in early June. The buzz is that India will receive clearance for manufacture of the GE F-414 engines which will power the Tejas MkII fighter jet.

Both countries need this deal. America plans to shift its production line from Europe to India, and we need positive control of this engine, insulated to the extent possible from sanctions and suchlike, since the Tejas MkII is meant to become the backbone of the Indian Air Force in the next decade.

However, there are multiple sticking points, with doubts on whether America will share manufacturing know-how for critical engine components like fan blades.

Vendors know that the day India cracks the gas turbine problem, we’ll never import another engine or jet.

It is the same with regional security where tugs, contradictions, and conflicts of interest prevail.

America needs India to counter China, yet it has done precious little to mitigate India’s multiple, near-existential regional security concerns, or offer much more than lip-service to India’s permanent membership of the United Nations Security Council.

Instead, America has encouraged needless political silliness by playing up minority victimhood chronicles in India, continues to monkey-balance India’s concerns with its need to maintain ties with Pakistan, and seeks to increase sales of American oil and gas to China.

A third major aspect is energy trade. Biden needs large, secure markets for the oil and gas he still hopes to produce and export in large volumes from American shale plays.

India and China are on top of that list for two major reasons: both nations enjoy a trade surplus with America, and long-term-high-volume offtake deals are exactly what Biden needs, to boost activity in his domestic upstream petroleum sector (see here for more details on sluggish drilling and production activity presently plaguing America).

India’s annual oil import bill is over 100 billion dollars. Consequently, and irrespective of whoever gets to eventually attend the banquet, Biden’s focus will be on trying every trick in the book to get a fat slice of that lucrative desi pie.

However, the Indian government would do well to ask itself a few questions before a decision is taken — especially on any long-term deals being considered for both oil and Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) — since the latest data shows that America may not be in a position to guarantee uninterrupted hydrocarbon supplies to India for fundamental structural reasons.

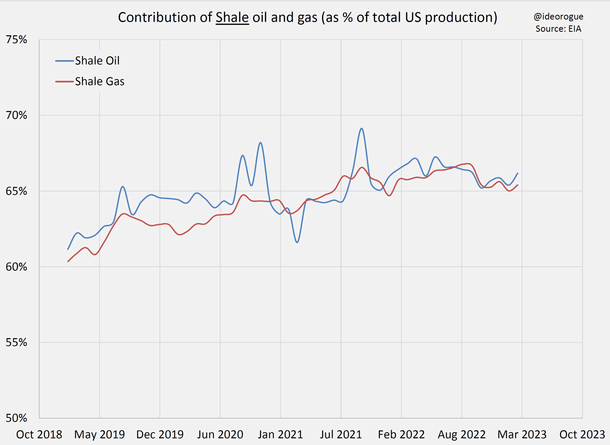

One, a full two-thirds of American oil and gas comes from shale plays as on date. But, the rate of growth slackened considerably during the pandemic years when demand slumped, and has, in fact, declined over the past year.

If these trends keep up, America will have progressively less oil and gas available for export.

As a chart below shows, if America had managed to re-establish the growth rates of 2017-2020, by promoting drilling activity during 2022, the contribution from shale plays would have crossed 70 per cent by now. But it hasn’t.

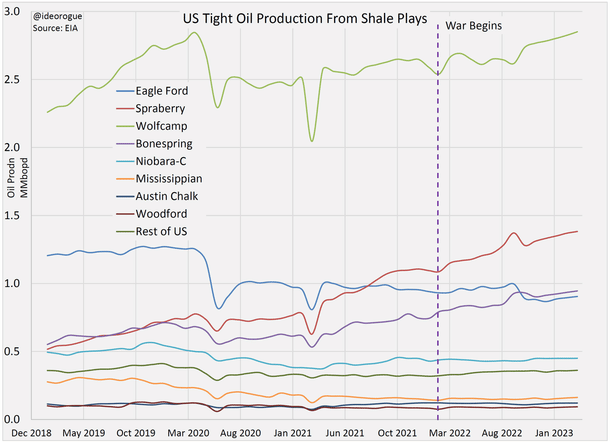

Two, the problems become more apparent when we study the performance of various shale oil plays under exploitation in America.

Of the 8 million barrels produced per day from shale plays, two-thirds come from three formations: Wolfcamp (the largest by far), Spraberry, and Bonespring. The rest are either into decline, or limping along on low plateaus.

The worry is that the three big plays have added only half a million barrels a day since the Russo-Ukrainian war broke out in February 2022.

So where is the additional oil going to come from, and more pertinently, when, if India does decide to import larger volumes of oil from America?

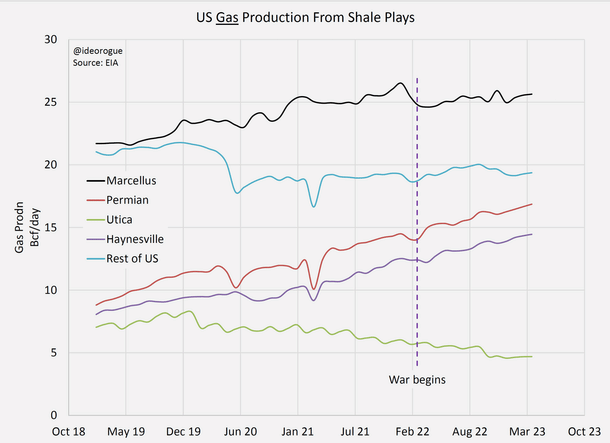

Three, the issues are broadly the same in the American shale gas sector. Currently, they produce around 80 billion cubic feet of gas a day (bcf/d) from shale plays, and have been able to increase output by only 5 per cent in the past year.

70 per cent of this gas comes from three plays — the Marcellus, the Permian, and the Haynesville. But their production levels have increased by only 5 bcf/d in the past year. And in the balance 30 per cent, gas production has gone up by just 0.15 bcf/d.

So, again, the question is: where is the additional gas going to come from, and when?

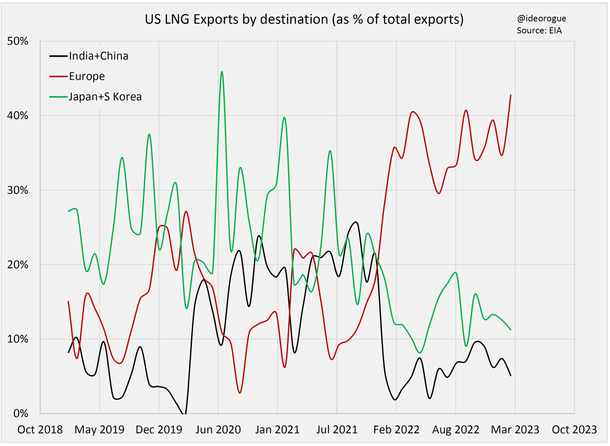

Four, the Americans may confidentially reply that if they are unable to increase domestic output, they could divert exports to meet their commitments to India.

But that is exactly what they did last year, when they hastily diverted large volumes of American LNG to meet European demands after the rupture with Russia. And that is what makes them an unreliable supplier in the first place.

India is not alone in this scepticism. As a chart below shows, America started raising LNG exports to Europe before the war began. And in prescient anticipation of things to come, large importers like China, India, Japan and South Korea, began sourcing less LNG from America.

Between 2018 and early-2022, roughly 30 per cent of American LNG exports went to Japan and South Korea, between 10 to 20 per cent to Europe, and around 20 per cent to India and China combined.

But today, Japan and South Korea import only about 10 per cent (green curve), and India and China only 5 per cent (black curve), while over 40 per cent of American LNG now goes to Europe (maroon curve).

The simple point, therefore, is that America is not in a position to meet multiple oil and gas requirements at the same time. If it wants to prioritise exports to Europe, then so be it, but it cannot have the cake and eat it too.

Having said that, it is also true that a smart American administration, which plays its cards right, offers competitive prices to India, and ramps up domestic production from shale plays, could win lucrative long term export deals for both oil and gas.

But the big question is whether Biden will be able to stand by his supply commitments? As things stand, it is doubtful if he can, and India should be wary of signing long-term import deals for oil and gas until the pace of drilling in American shale plays picks up considerably.

Venu Gopal Narayanan is an independent upstream petroleum consultant who focuses on energy, geopolitics, current affairs and electoral arithmetic. He tweets at @ideorogue.