Economy

Of Counsel And Opinions: Why Critics Of GST Reforms Are Wrong

Samridh Joshi

Sep 16, 2025, 10:48 AM | Updated 11:51 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

On 15th August 2025, the Prime Minister announced landmark reforms to the GST system from the parapets of the Red Fort. The GST Council followed the lead and brought in critical amendments in the GST rate structures and processes in its 56th meeting. While the reforms mark a move to one of the simplest indirect tax structures in modern Indian economic history, criticism arrived rather quickly from various quarters.

Prominent individuals have raised doubts over the intentions and consequences of the reforms, including the former Chief Economic Advisor of India, Dr. Arvind Subramanium, former Finance Secretary, Subhash Garg, and former Finance Minister, P. Chidambaram.

Recently, Dr. Subramanium argued that the GST reforms endanger the fiscal sovereignty of the states, betray promises, and have a questionable impact on macroeconomic stability. Subhash Garg has accused the government of trading “Fiscal Pain for Electoral Gain” while Mr. Chidambaram has labelled them “Too Late”.

In the course of a proper analysis, it appears that most of the critiques have sprung up from a prejudiced view of the subject or political expedience and do not hold up to scrutiny.

GST Reforms: Too Little Too Late?

As Dr. Subramanium himself admitted in his works, the process of indirect taxation reforms has been a big pain point for any central government with a reformist agenda. Novel ideas were met with fierce resistance from states which feared loss of fiscal sovereignty. Caution had to be followed before bringing up the very idea of GST on the table.

One of the major reforms preceding GST was the abolition of the Planning Commission, an institution that stifled fiscal rights of the states under the garb of economic planning. In the satirical words of a now retired staff member, “State Ministers used to fall at our feet in the prospects of sanctioning funds for the States”. The organisation was revamped into a NITI Aayog and India moved from an era of forced fiscal planning to cooperative federalism.

The late Arun Jaitley led a painstaking endeavour to convince state governments of the GST Bill and the amendment was passed unanimously. Bureaucratic hurdles clogged the process, and so did numerous election cycles and political expedience. It is in these troubled waters that the NDA government has painstakingly delivered a host of taxation reforms and finally framed and passed the GST reforms. While the idea was mooted by the Atal Bihari Vajpayee-led government, the following UPA could not act on the same for nearly a decade.

Eight years, while a seemingly long duration of time, has been essential to convince the states that the GST has not burdened their exchequer and that the GST Council has worked in good faith towards their fiscal interests. This process of the handshake instead of the brick is precisely why the reforms are neither little nor late but reflect that the government is working in the same spirit that it is accused of belittling.

Revenue Loss: Do the Numbers Add Up Well?

It is expected that on a cursory glance, the GST reforms will burden the exchequer due to expected revenue losses. As the reforms reduce the average effective GST rates to about 9.5 per cent from about 11 per cent, indirect taxation revenue will decline, considering no other factor that can influence the revenue and barring any behavioural change.

The Revenue Secretary has stated on record that the government expects a loss of ₹48,000 crores based on FY23-24 for the remaining year, and ₹93,000 crores is expected for the next financial year.

However, Subramanium’s analysis has come up with a figure of ₹1.5–₹2.1 lakh crores, nearly thrice the figure of the government estimates. Mr. Garg presents an even higher figure of ₹2 lakh crores. This is an extremely bizarre figure since Garg’s estimates add up the removal of GST Compensation Cess, an additional tax over the slab rates, meant to compensate the states for any loss of revenue under the GST system. What he does not account for is the fact that the GST Compensation Cess was meant to be a temporary measure and was slated to be removed in 2026 irrespective of reforms.

On the contrary, countering these estimates, SBI Research has predicted an expected loss of ₹60,000 crores to ₹1.1 lakh crores (ignoring consumption gains). Fitch projects a fiscal cost of 0.2 per cent of the GDP, or ₹66,000 crores (nominal). Crude calculations project an approximate revenue loss of ₹1.1 lakh crores (excluding cesses). Further, the data of GST calculations is not reliably available at micro levels in terms of slabs. In short, the numbers do not add up well and criticisms relying on projected revenue losses should be taken with a pinch of salt.

Macroeconomics of GST Reforms: Missing the Demand Multiplier Variable

For one, both Subramanium and Garg do not account well for the demand multiplier variable. Demand multiplier arises as a variable pushing up consumption spending as consumption is elastic and buoyant and influenced by tax rates. While Subramanium seems to factor it in to a lesser extent, Garg completely leaves out the variable in his estimates of revenue projections.

In his analysis, Garg resorts to vague citations of automobile demand estimates and, based on one data point, removes the variable altogether. Garg also mistakenly calls it a zero-sum game while ignoring the fact that multiplier factors for personal consumption and government spending are completely different, with the former having a much higher magnitude than the latter. This point requires careful analysis.

SBI Research has projected the consumption numbers to go up by 0.6 per cent of the GDP. With an initial consumption injection of ₹70,000 crores, iteratively the reforms are expected to inject ₹1,98,000 crores into the economy by means of consumption buoyancy. Contrary to critics, it predicts a net revenue loss north of ₹3,000 crores. Although the analysis is not extremely robust, it provides a ballpark estimate of the returns. With this, the impact of GST reforms is expected to be non-existent to near positive.

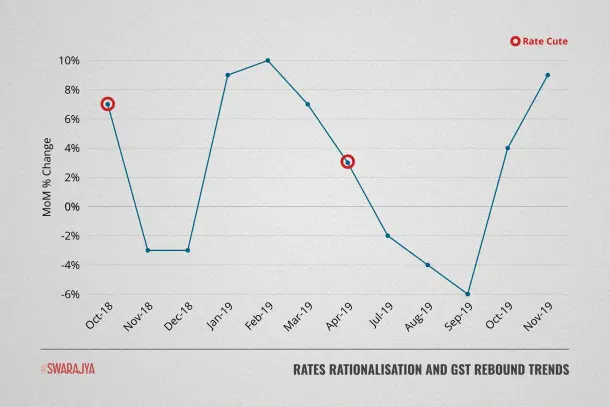

CPI inflation for goods is expected to decline by 20–25 basis points, freeing up household income for consumption demand. History has been kinder to indirect taxation rate reductions in India. While an immediate reduction in rates can cause a short-term dip of around 3–4 per cent month-on-month, revenues typically rebound with sustained growth of 5–6 per cent per month. The same is expected for the present set of reforms. This is expected to go up further as cess is subsumed in the 40 per cent bracket and squared off.

Nudge: Behavioral Economics of GST Reforms

The father of behavioural economics, Richard Thaler, suggested liberal paternalism in the form of nudges or non-coercive tools to stimulate optimal behaviour. India has had a painful history of non-compliance in taxation, leading to significant losses. The government estimates that close to ₹2 lakh crore in GST collection is lost to non-compliance and evasion. To counter such instances, Thaler had suggested simplification of tax structures.

The GST reforms walk well on the path laid down by behavioural economists. First, the tax is simplified to only two slabs and one for sin goods, making the tax truly simple. Second, input tax credit structures have been corrected and inverted duty structures resolved to a large extent. Third, the GST reforms come with features aimed at improving ease of compliance, including automated registrations and refunds based on advanced data analytics.

It is this nudge that made the GST system a success. Collections have risen sharply, with the tax base increasing from ₹45 lakh crore to ₹173 lakh crore over the past decade at a CAGR of 14.4 per cent. It is a no-brainer that the same would be expected to accelerate under the new GST reforms. These points are expected to nudge the taxpayers and raise GST revenues for the government but have been ignored by the critics.

On Fiscal Federalism: States Have Little to Lose

Perhaps the harshest critique of GST reforms has come in the form of the usual accusations of hurting fiscal federalism. Subramanium writes, “The states argue that they gave up sovereignty over indirect taxes only because they were told they would collect more revenue under GST”.

For starters, the promise has been fulfilled rightfully by the Centre. The Centre promised 14 per cent indirect tax revenue growth annually and has in fact delivered more than the said amount. States have been devolved a net of ₹63,000 crore more than revenue projections and incremental gains combined at an aggregate level.

Due to the COVID pandemic, reduced revenues through the states’ share of GST were compensated through the extension of the GST Compensation Cess and commensurate borrowings by the Centre for the states. Thus, fiscal interests of the states were upheld even during times of crisis. The GST structure has been developed in favour of states with more than 70 per cent of the aggregate GST revenue going to the states. The GST Council, with a 75 per cent majority vote requirement, assigns one-third voting power to the Centre and two-thirds to the states. Out of 52 meetings, all decisions but one were reached through consensus.

GST has improved tax buoyancy from 0.72 (pre-GST) to 1.22 (2018–23). Despite compensation ending, state revenues remain buoyant at 1.15. Without GST, states’ revenue from subsumed taxes from FY 2018–19 to 2023–24 would have been ₹37.5 lakh crore. With GST, states’ actual revenue amounted to ₹46.56 lakh crore. It is expected that buoyancy will see a further increase with the GST reforms and offset potential revenue losses to a large extent.

The idea of fiscal federalism was envisaged in the constitution to provide means for better governance outcomes for the population and aid the states in administering better quality of life metrics including healthcare and education. The GST reforms aid the states in these duties by reducing healthcare goods to a minimum slab of 5 per cent and exempting insurance covers from the taxation slabs. Education, FMCG and consumer goods have also been reduced to the minimum slab. GST reforms are in line with the responsibilities of the states under the constitution and not contrary to the same.

Finally, major sources of state revenues including fuel and alcohol have not been impacted and autonomy of states has been maintained on the same. The minutes of GST Council deliberations are yet to arrive but it is expected that except for certain reservations, the reforms have been approved by an overwhelming majority of the states. Except for political disagreements, fiscal sovereignty has never been a casualty of indirect tax reforms.

Towards a Good and Simple Tax

The GST reforms are a landmark moment in India’s taxation history after the operationalisation of the scheme itself. Major reductions in GST rates have been announced in the interest of citizens. Process reforms have been embedded in the reform agenda and long pending issues, including operationalisation of the GST Appellate Tribunal, are set to be resolved. Despite minor losses in revenue in the short run, the impact from FY27 onwards is expected to be minimal.

The reforms are expected to ease demand-side stress in the economy and promote spending and consumption revival. This is expected to add 100–120 basis points to the GDP growth rate. Reforms will also help the RBI continue its accommodating stance and extend the quantitative easing cycle. Further, the timing of the reforms makes them well suited to counter international trade pressures that have been mounting of late.

The Next Generation GST Reforms 2025 mark a transformative and citizen-centric step in India's indirect tax system. Critics should embrace careful optimism and add to constructive debate around the way forward instead of raising doubts on an act that was long overdue.

Samridh Joshi is an Economist and Public Policy Consultant. He is an alumnus of IIT Kanpur and UC3M Madrid. Views are personal.