Economy

Reluctant Reformers And The Missing Revolutions

Praveen Patil

Aug 06, 2015, 06:29 PM | Updated Feb 11, 2016, 09:58 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Those who rue the absence of the so called ‘big bang’ reforms are missing the far-reaching initiatives of the PM in the rural economy.

P.V. Narasimha Rao , the original economic reformist prime minister, often rejected the idea that he was the Margaret Thatcher of India. He strongly believed that he was in the mould of Willy Brandt, a social democrat to the core who argued that economic reforms were merely an apparatus to increase government revenues which, in turn, could lead to increased public spending and equitable wealth distribution. Contrary to general perceptions, Narasimha Rao summarily rejected the ‘trickle down’ economic philosophy and believed in greater social spending.

Yet, in the first few years of the 1990s, his government was singularly responsible for some of the most far-reaching reforms, possibly without realizing the depth of those measures at times.

Industrial de-licensing was one such simple reform that according to me went largely unnoticed by the intelligentsia of that era but has led to the creation of the Indian economic juggernaut.

When he took oath of office in May last year, Prime Minister Narendra Modi had raised tremendous hopes across the world that he would be the first truly reformist leader of India. A year later, most economists and business analysts have started to feel disappointed.

One of the favourite questions that is often asked in the media is “where are the big bang reforms?” Is Modi really scared of revolutionary reforms?

It is often argued that the Indian DNA is evolutionary in nature, and revolutions are intrinsically unpalatable to us. For instance, Mahatma Gandhi led us on a slow, tiring path to achieve independence through satyagaraha rather than trying to fan a revolutionary uprising of the masses. The fact, however, is that this evolutionary spirit is not an Indian civilizational delinquency but a Victorian gift to us. For 120 years between 1800 and 1920, India virtually stood still when both India’s population and GDP grew at a pathetic 1 per cent every year while the world took giant leaps through the industrial revolution. Those 120 years of stasis may have scarred the Indian psyche so deeply that the process of slow motion became an extension of our being.

However, after two decades of reforms ushered in by the Narasimha Rao government, a socialist republic had started to smell a revolution in the air of 2014. For the restless 81 crore young Indians below the age of 35, Modi came to symbolize a revolution which could liberate India from its inherently systemic slow motion.

Thus the answer to the question of whether Modi is really scared of revolutionary reforms depends on who is asking the question in the first place. Modi seems to have understood his mandate of 2014 as primarily a vote for structural reform of the largely agrarian rural India which hardly finds space on the stock-market obsessed business channels or the Delhi-centric business broadsheets. There are three disruptive revolutions happening in rural India which could be potentially transformational by 2020.

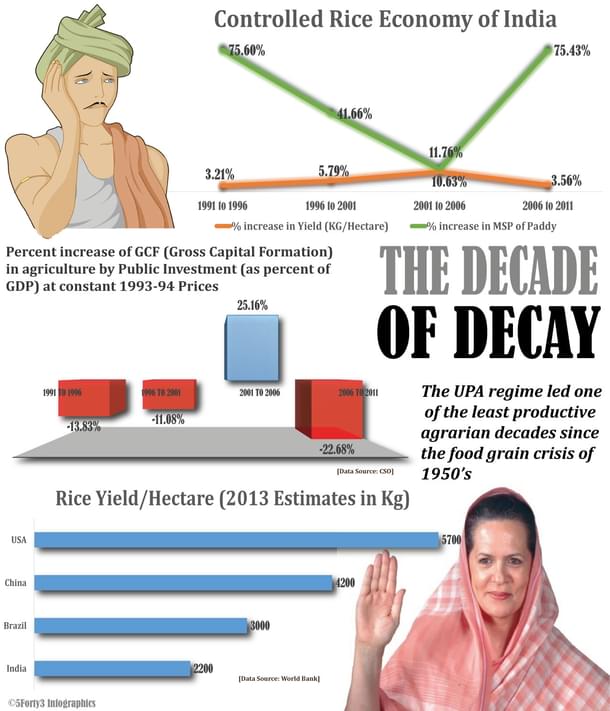

The first part of the agrarian revolution comes from the right economic path. For the last 10 years, the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government blindly increased the minimum support price (MSP) for rice and wheat hugely just to keep a section of the voters happy (though the quantum did come down in the last two years) but eventually the voters punished it for growth stagnation. Data shows very clearly that while MSP for paddy increased by a whopping 75% from 2006 to 2011, yield growth per hectare slowed down to a mere 3.5% in the same period. Data further shows that the growth of rice yield per hectare was the highest in the period from 2001 to 2006 at 10.63% when MSP also increased at a much slower rate of 11.76%. In fact, in the last decade, Indian agronomy has seen the most unproductive phase since the pre-green revolution era in relative terms to GDP.

This strange correlation between MSP and yield per hectare tells a story of its own; that politicians, in their mad rush to keep the voters happy, actually do more harm to an average farmer by increasing MSP, except where there is a genuine need to hike rates due to increase in input costs. One of the primary reasons for decline in yield per hectare during the years of higher MSP is simply because governments did not invest in technological advancements for rural India and instead concentrated on the populism of MSP. Gross Capital Formation (as percent of GDP) through public investment actually declined by 22% in 2011 as compared to 2006*.

The Modi government, for the second year in the running, avoided biting the bullet and only marginally increased MSP for rice and wheat. This is no mean achievement coming in the backdrop of elections in the largely rural Bihar and the weatherman predicting a deficient rainfall. The fact that Modi is willing to take the temporary brunt of the rural voter to create a better agrarian economy for the future is nothing short of a mini-revolution. In fact, it may have started bearing fruits already this year as there has been a whopping 400% increase in oilseed cultivation in the sowing month of June, indicating a pattern shift. The next challenge is to liberate agricultural produce from the political control of agricultural produce marketing committees (APMCs) which would truly unshackle the Indian farmer from the crutches of MSP and the Modi government has already chosen the digital pathway to achieve this.

The second part of the revolution in agronomy comes in the form of fiscal prudence. As per the Economic Survey report, India spends 2.33% of its GDP or Rs 2,35,790 crore (in 2014-15) on fertilizer, grain and sugar subsidies. These agricultural subsidies are provided both at the production and point of sale level – subsidies for urea manufacturers and indirectly through MSP for rice, wheat and sugar – as well as at the point of consumption level – controlled MRP of urea and subsidized rice, wheat and sugar at the PDS.

The economic benefit of fertilizer subsidy is mainly derived by urea manufacturers whereas the farmer benefits very little; in fact, the government ends up subsidizing lavish lifestyles of failed businessmen like Vijay Mallya through the urea route. 15% of the PDS rice, a whopping 54% and 48% of the PDS wheat and sugar are lost in leakage (although the PDS costs are not subsidies directed towards agriculture). Furthermore, according to the Economic Survey Report 2014-15, only 53% of the remaining 85% of the PDS rice actually reaches the bottom 3 deciles of the population for whom the subsidy is intended. Similarly, only 56% of the remaining 46% of the PDS wheat actually reaches the poor.

A simple back of the paper calculation tells us that more than Rs 1 lakh crore that the government spends on agricultural subsidies evaporates into a black hole. If this Rs 1 lakh crore were to be deployed to develop better agricultural infrastructure, it would be far more beneficial to rural India. It is in this regard that Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana (PMJDY) could prove to be a hugely disruptive reform measure as 60% of all accounts (10.4 crore out of 17.2 crore accounts) opened in the last 11 months belong to rural households. If all the agrarian subsidies are directly transferred to the beneficiary’s account, after biometric verification (through tools like Aadhar), it could potentially mean an increase of a whopping 1% of the GDP for the government.

The third part of the rural revolution is a socio-economic disruption that can completely alter the way Indian villages are quantified as economic units. Deep rooted socialist tendencies of our policy makers had ensured that rural India always remains dependent on the largess of the ruling class. Be it agricultural loan waiver schemes or MNREGA, villages were always expected to be at the mercy of governments and their lady bountiful acts.

The Atal Pension Scheme and 3 different insurance schemes that the government has linked with the PMJDY bank accounts have tremendous socio-economic scale that many commentators and economists have failed to understand so far. Even if the premiums and monthly emoluments are as little as Re 1 to Rs 1400, these economic measures can have a huge two-dimensional impact.

For the first time, asset classes like insurance and pension schemes are being deployed effectively in Indian villages which creates a sense of ‘ownership’ among the rural masses that is radically different from government doles like MNREGA.

Rural consumption patterns are predominantly ‘present’ in nature because poor rural households try hard to subsist in ‘today’ without the luxury to plan for tomorrow. These consumption patterns can be fundamentally altered through orientation towards a better secured ‘future’ by these effective asset classes.

Thus, Modi may come across as a reluctant reformer to a regular Sensex watcher. He certainly is no Margaret Thatcher. Yet, his structural rural reforms may create a revolution unbeknownst to the Delhi-based intelligentsia. A decade from now, Modi will probably be hailed as the visionary who created the rural market expansion by revolutionizing village consumption patterns and tapping surplus rural labor productively, till then, let us keep on asking, where are the big bang reforms?

Analyst of Indian electoral politics and associated economics with a right-of-centre perspective.