Economy

Why DeMo Misfired: Here Are Some Of The Lessons We Can Learn From Fiasco

R Jagannathan

Aug 30, 2018, 03:48 PM | Updated 03:48 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

The polemics over demonetisation (DeMo) briefly flared up again this week when the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) released its annual report for 2017-18, which included the information that Rs 15.31 lakh crore of the Rs 15.41 lakh crore outstanding Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 notes as on 8 November 2016 had been returned to the system (read the relevant section of the annual report here).

It is difficult to see how this number is substantially different from what was disclosed in the last annual report (2016-17), when the amount was mentioned as Rs 15.28 lakh crore. The Rs 0.03 lakh crore difference is a rounding error at best, and could have easily been the result of some cash that had still not been counted or left out by mistake.

But even if there is not much new information over which to debate the costs and benefits of demonetisation, we need to give it a shot. We should map the results against what the reasoning behind demonetisation was, and whether even the post-facto shifting of goal-posts (moving the economy towards a less cash one) can show demonetisation in better light.

When demonetisation was announced on 8 November 2016, the stated goals were to reduce the stock of black money, throttle counterfeiting, and strike at the roots of terror funding; two more goals were added as an after-thought when the inflows of the demonetised notes in November 2016 exceeded official expectations. These were a move towards a less-cash economy (through the promotion and adoption of digital modes of payment), and capture of more information about who held what amounts of cash.

Indirectly, it was suggested that the political goals of demonetisation included trapping large chunks of demonetised notes outside the system, which would have reduced the Reserve Bank’s liabilities, and the “savings” paid out as a special dividend to the government. This, in turn, would have allowed the Narendra Modi government to claim that it had confiscated the ill-gotten wealth of the rich and given it to the poor in some form. But with 99.3 per cent of the notes coming back to the system, it is clear that this objective, though never stated openly, was a 99.3 per cent failure.

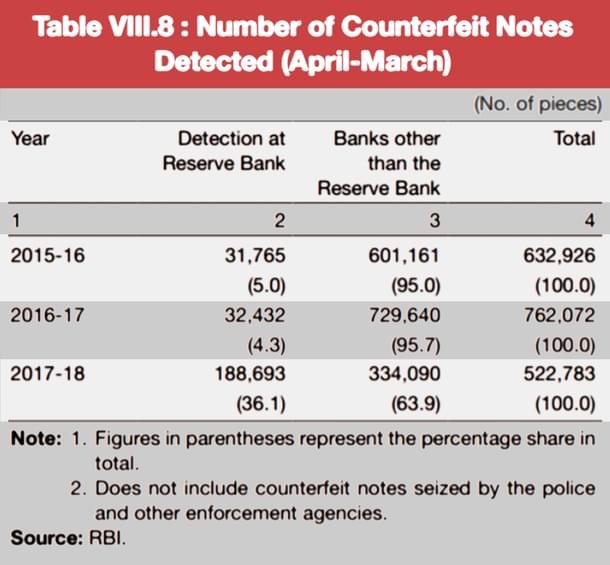

There are no clear numbers to indicate that terror funding was substantially impacted, but it is more than likely that there was some impact in the short term. As for fake notes, the Reserve Bank’s latest annual report does indicate (see table VIII.8) a significant drop (over 31 per cent) in their detection, so one can call this objective as partly met, but at huge cost.

Broadly speaking, it is clear that the costs outweighed the benefits. The costs were economic disruption and loss of gross domestic product (GDP) in a few quarters, loss of incomes for businesses and people who were part of the cash economy, especially agriculture, real estate, construction and the informal sector, higher currency printing costs for the central bank and loss of revenues to government as economic activity dropped and the Reserve Bank also cut its dividend, and loss of profits to the banking system in those months when the focus shifted to managing the exchange of old notes instead of addressing the larger problem of recognising bad loans in the system and recoveries, etc.

The benefits claimed so far are an increase in tax compliance and revenues, higher digitisation levels in absolute terms, etc. But the problem is we can’t clearly state that these gains were due to demonetisation, since the goods and services tax (GST) provided an added impetus to formalisation from 1 July 2017. Going forward, most of the gains in eliminating black money and tax compliance will be the result of GST and the rising formalisation of the economy, not DeMo. The Real Estate (Regulation & Development) Act is bringing the same discipline to large parts of the real estate sector, which is the big generator of black money.

Those companies that took advantage of the forced shift to digitisation, especially banks and financial technology companies, did gain in the short run (Paytm is a great example), and so did petrol bunks, electricity companies, and municipal authorities, as they got a short window after 8 November to accept payments in old cash – a window used by many holders of black money to dispose of a part of their illegal money hoards. The huge inflows into banks also lowered interest costs for borrowers in 2017 before the trend started reversing towards the end of the year and this year. Bank profits from treasury incomes also briefly spiked, as their holdings of higher interest securities rose in value.

It is possible to claim esoteric benefits from DeMo, including the often heard one that the system needed a shock treatment; maybe, but once the shock was absorbed, it left behind a shortage psychology that may have increased demand for cash. Nothing exacerbates the hoarding instinct of human beings as much as fears of shortage.

Clearly, the gains of DeMo were ephemeral, and the costs longer-lasting.

One can try and work out actual estimates of both the costs and benefits, but suffice it to say that trying to put a number to anything (which will always be contested) is not going to make any difference to the assertion that demonetisation misfired. If this were not so, the Modi government would still be talking about its benefits. That it has gone quiet on DeMo suggests that it is aware that the costs have been unacceptably high.

It is, thus, more productive to understand why DeMo failed, and how it could have been done better, assuming it had to be attempted at all (no one will attempt it anyway in the foreseeable future).

Execution: Even assuming that the need for secrecy meant that enough notes could not be printed to replace the demonetised ones, there was no need to have done the job in one go, where 86 per cent of the notes in circulation were cancelled overnight. At the very least, a two-stage demonetisation, with Rs 1,000 notes going first, and Rs 500 after two months, would have ensured that the economic damage was minimised.

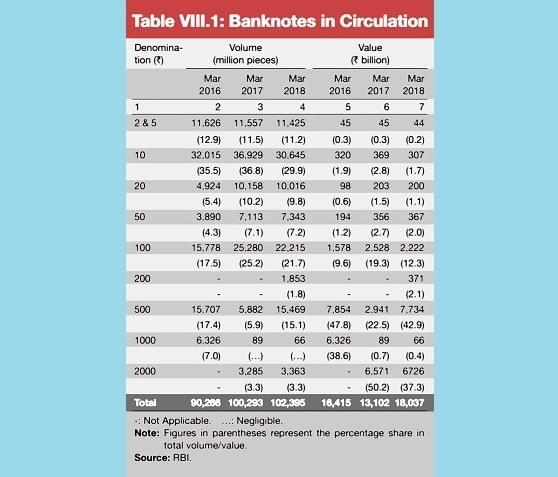

Ecosystem: In 2016, the ecosystem for greater digitisation was simply not in existence, though digital payments (or, rather, non-cash modes of payment) had been growing organically, using RTGS (real-time gross settlements), NEFT (national electronic funds transfer), IMPS (immediate payments system), internet and mobile banking, and e-wallets. Demonetisation forced many people to shift in the short-term to these forms of payments, but many moved back to cash modes once the immediate crunch had ended. Banknotes in circulation now are much higher than on 8 November 2016 (Rs 18 lakh crore as on 31 March 2018, see table VIII. 1 from the RBI annual report). People are simply stocking up cash to their own old comfort levels. More importantly, the cyber-safety architecture to protect people, even poorly educated ones, using digital modes is simply not good enough.

Electoral reform: A key driver of the demand for cash is electoral funding. It is an open secret that candidates fund their election machinery largely through cash, both to stay within the unrealistic spending limits prescribed by the Election Commission of India, and to “bribe” voters and pay their supporters to bring voters to the booth. This means that without electoral funding reforms, the demand for cash during election times will remain high. This is exactly what we saw in the run-up to the Karnataka assembly elections earlier this year, when hundreds of ATMs ran dry and cash disappeared in some pockets of many states, including Andhra Pradesh, Telangana and Madhya Pradesh. Until cash is reduced in electoral funding, moves towards a less-cash economy are unlikely to work.

Laundering: The Jan Dhan account, intended to provide no-frills banking to every household, preceded demonetisation by more than two years. Many were dormant, or had very few transactions. But when the old notes were cancelled, those with excess holdings used other people’s accounts to deposit their money, with the benami holders getting a cut from the deposit. In theory, now that large deposits have an address, it should be possible to trace the money back to their true owners. But this could not have been done for two reasons: it would have meant harassing the poor; and two, the tax department simply did not have the capacity to chase such accounts without creating terror everywhere. Jan Dhan thus worked as a laundromat for the tax evader, and – as a byproduct – also helped the poor make some commissions in the bargain. The huge popular support for demonetisation in the initial months is partly explained by the fact that the poor, even while suffering long queues outside banks, saw the rich running helter-skelter to get their money laundered. The poor suffered, but they also witnessed ‘Dhanna Seth’ suffering in front of their eyes. Their gain was pure schadenfreude.

Clearly, the goals of demonetisation can be justified, but the same could have been achieved by doing things differently. The lessons are thus the following:

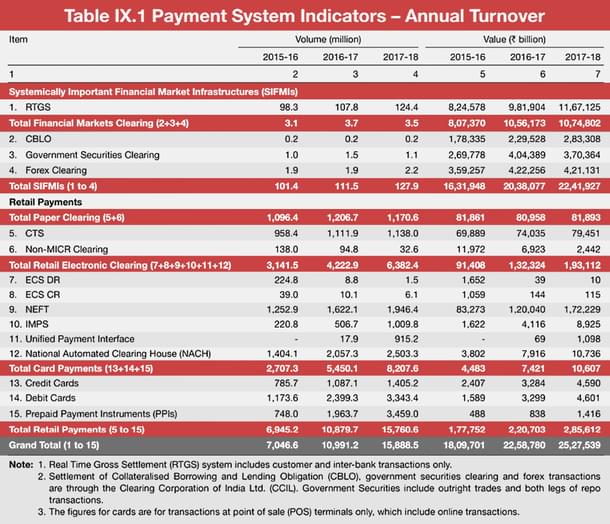

First, a less-cash economy is desirable, but it needs to be preceded by strong cyber-security and privacy laws, and the pressure to go digital should be attempted geographically, city by city, district by district. It is only when the geographical ecosystem in which rich, middle class and poor people transact digitally with one another that we can move towards a less-cash economy. Unless almost everybody feels he or she can transact with less cash, the total demand for cash will not fall significantly. It cannot be done purely through the abolition of fees for card or wallet payments. In any case, non-cash modes of retail payments are growing robustly. Between 2015-16, 2016-17 (the demonetisation year) and 2017-18, retail electronic payments rose 45 per cent in one year, and again by the same proportion in the last financial year. Retail electronic payments include payments by NEFT, IMPS, wallets, UPI payments, electronic bill and EMI debits, and credit and debit cards (see table IX.1 from the RBI annual report).

While cheque payments stagnated at around Rs 81-82 lakh crore between 2015-16 and 2017-18, retail electronic payments have effectively more than doubled to Rs 193 lakh crore – which accounts for two-thirds of all forms of formal retail payments. Demonetisation could have contributed to this, but the system is increasingly comfortable with non-cash payments.

Second, to disincentivise cash payments for all but small value transactions, the government must steadily withdraw (without making them illegal tender) Rs 2,000 and Rs 500 notes and replace them with Rs 100, Rs 200 and lower value notes. This will involve costs, since these higher-value notes will have to be replaced with a larger volume of lower value notes to avoid another crunch, but transactions that earlier involved cash payments (as in real estate) and private payments without bills will steadily be discouraged. No one wants to hold a physical mountain of cash in Rs 100-200 notes.

Third, electoral and tax reforms are vital if we want less cash in the system. Spending limits have to be more realistic, the state must fund candidates, and corporate funding of political parties must be made more transparent. Lowering GST and income tax rates will help smaller companies and kirana stores to move away from cash transactions.

Fourth, the discretionary powers of ministers and bureaucrats to grant favours, and human interfaces between government and citizens, must be reduced to a minimum at every level of government. This will, on its own, quell the demand for bribes and cash payments.

Merely constricting cash supply – which is what DeMo did – won’t make much of a difference to the demand for cash, except in the short term. Over the long term, you have to deal with the demand side too.

That is a big takeout from the failure of DeMo.

Jagannathan is former Editorial Director, Swarajya. He tweets at @TheJaggi.