Economy

Will The Crouching Tiger ‘Defang’ The Dragon In Future? Maybe, As Cost Of Production Skyrockets In China

Karan Bhasin

Dec 29, 2019, 12:28 PM | Updated 12:28 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

The brief window of opportunity to relocate companies from China due to the ongoing trade war seems to have come to an end as US-China complete the phase-1 of their trade deal.

So does this mean that we’ve missed yet another window to kick-start our manufacturing revolution? Perhaps not.

The implicit understanding behind the positive impact of the trade war was that it would act as a catalyst and bring firms to India.

Indeed, the trade war did amplify the process of firms exiting China and some of them did come to India too, while many of them went to Vietnam or Cambodia.

However, the end of the trade-war is not the end of an opportunity for reorientation of the global supply chains.

For starters, the recent trade disruption exposed the extent of vulnerabilities of several companies to their overdependence on Chinese suppliers.

Consequently, many of them have hedged their bets and are looking to further diversify their suppliers and spread them across countries to avoid such a scenario in the future.

A point, however, often missed in mainstream discussion about China and its manufacturing prowess is the significant growth of wages that it has witnessed over the last 10 years.

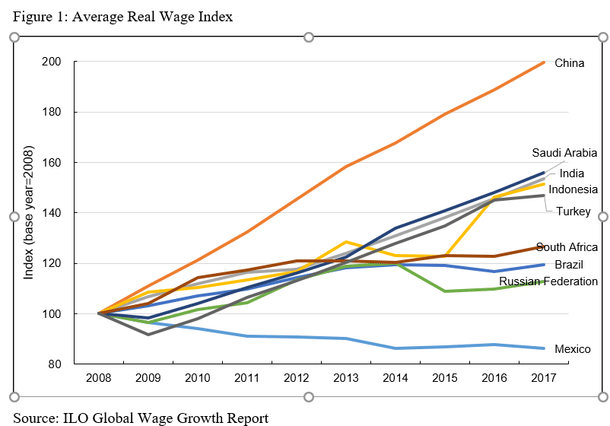

The International Labour Organization tried to capture the extent of increase in real wages for developing countries by taking 2008 as the base year with the value of 100 for each country.

As it turns out, China witnessed one of the best increases in real wages which was followed by Saudi Arabia and India.

Mexico, incidentally, witnessed a reduction in its real wages since 2008 onwards.

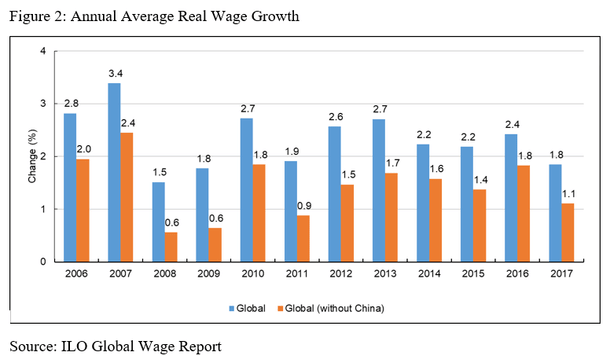

ILO also provides us with the data on wage growth for the world with and without China.

The difference itself suggests the extent of wage growth that China has witnessed over the last two decades.

This recent growth of average real wages in China has a lot of interesting economic implications for the third decade of the 21st Century as it is important to recognise that wage is indeed an important component of the cost of production.

The first implication is that, somewhere in the middle of the current decade, China became too expensive for labour-intensive manufacturing.

Therefore, the Chinese story was somehow over some 3-5 years before the trade war started.

This is interesting because it suggests that companies were indeed relocating even before the trade war.

This process was indeed slow until the trade war, which amplified the process and brought the issue as a key point of discussion.

On the one hand, wages have shot up in China due to its growth while on the other, many are hesitant to partake in labour-intensive manual jobs and, therefore, we’re witnessing a shift in China towards capital-intensive sectors.

The big automobile push in recent years by Chinese companies could be an early indication of this trend which will grow further over the coming years.

The recent trade disruption resulted in significant reorientation of the supply chain such that our other competitors seem to be satiated as their labour market gets too tight.

In contrast, India continues to have a huge population that can serve as a labour force for manufacturing sector and a vibrant market for finished products.

Since the 1991 reforms, the world has indeed looked up to India with a lot of hope — and rightly so, we’ve the right set of conditions required to create a dynamic modern economy.

However, our growth rate has been elusive as we fail to sustain a 7.5-8 per cent growth for a longer period.

Things did change in 2014 as the world yet again started to keenly pay attention at what’s happening in the world’s largest democracy and the third largest economy (in PPP terms).

The steady investments in infrastructure, systemic easing of processes and the recent corporate tax cut do create a conducive policy environment for the take off of Indian manufacturing sector, especially at a time when labour-intensive manufacturing would look at other viable alternatives.

However, we can do a lot more on the policy front as our cost of capital, especially the real cost of capital continues to be high.

A key challenge would be to reduce the cost of capital and dismantle the regulatory aftertaste of pre-1991.

Factor market reforms such as land and labour will indeed be essential to ensure we unshackle our productivity by reallocation of resources.

We may also have to re-imagine our trade policy gradually opening more to ensure we are interlinked with the global supply chain.

This would require us to get rid of our wonky socialist-era agricultural policies and move towards a smart cash transfer mode of providing subsidies to our farmers.

As long as we’re able to undertake some of these bold reforms in the early years of the coming decade, one can safely assume that the third decade of the 21st Century would belong to India and in December 2029, we may witness a lot of books and articles narrating the tale of the Great Indian Tiger.