Ideas

Covid-19 Overview: Why Last Week's Data Is Of Concern And Where The Spikes And Plateaus Are Coming From

Venu Gopal Narayanan

Jul 10, 2021, 01:44 PM | Updated 01:44 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

This week saw a slight rise in the number of Wuhan virus cases being reported across the nation. While the increase was less than daily numbers from the week before, this sustained rise across three consecutive days merits detailed investigation.

This is the situation in the country today:

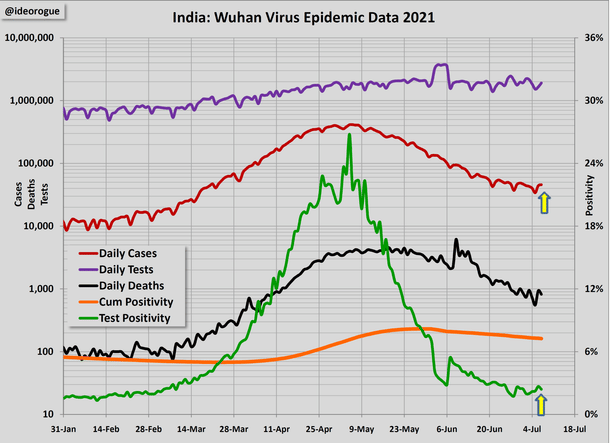

As we can see from the chart above, the consistent decline of daily cases (red curve) has eased off into a plateau, with a brief rise at the end. Similarly, the test positivity ratio (TPR; green curve) has started rising again after bottoming out.

Daily death data has been exhibiting fluctuations through June and July (black curve). This is primarily a function of some states revising their fatality tallies upwards. Still, a distinct downward trend is visible.

Testing levels (purple curve) are holding steady, which is a good sign, but the rate of decline of the cumulative positivity (CP; orange curve) is not as high as it should have been by this time, if June trends had been maintained.

If CP had followed the decline path set in early June 2021, it would have been down to under five per cent by now. Instead, it is still at an unhealthy seven per cent, and not declining fast enough.

All in all, a working inference is that while the second wave has abated from most of the country, it is still festering strongly enough in certain pockets, to potentially trigger a nasty third wave if we let down our guard. This threat is being exacerbated by reckless tourists crowding into cramped holiday spots, and an air of complacency on the street.

Therefore, the focus of this piece will be on where the dangers lie, why things are the way they are, and what state governments should do. The Prime Minister has already identified Maharashtra and Kerala as key provinces of grave concern, but these are not the only ones; there are other problem areas on the list as well.

As explained earlier by Swarajya, the most important monitoring parameter on date is the cumulative positivity of a state, rather than TPR, since CP is the best indicator of how exactly a state is fighting to eradicate the Wuhan virus. The standard thumb rule is that a state may be deemed to be in the clear if its CP is brought down to below the four-five per cent band.

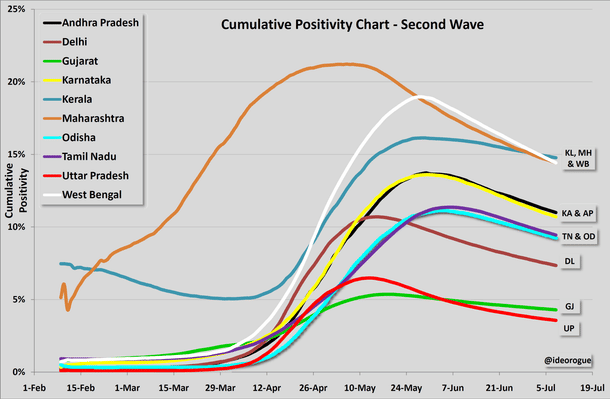

However, as chart 2 above shows, a number of states are yet to hit that safety mark, even though their TPR has come down to below 1-2 per cent. This is both a cause for concern, and a warning to those states, that they had better girdle their administrative efforts if they are not to trigger a third wave nationally.

The cumulative positivity in Kerala, Maharashtra and West Bengal continue to hover near the 15 per cent mark. Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh, though lower, are still in the double digit band. The CP in Tamil Nadu and Odisha may have finally dipped into single digits, but at the rate at which declines are taking place, it is doubtful of they would hit the 4-5 per cent band before mid-August. That is a month too many.

In Delhi too, while CP decline rates were encouraging over May and half of June, they have regrettably slowed since then. In contrast, the two bottom curves of chart 2, for Uttar Pradesh and Gujarat, show what can be achieved if a state government puts its nose to the grindstone.

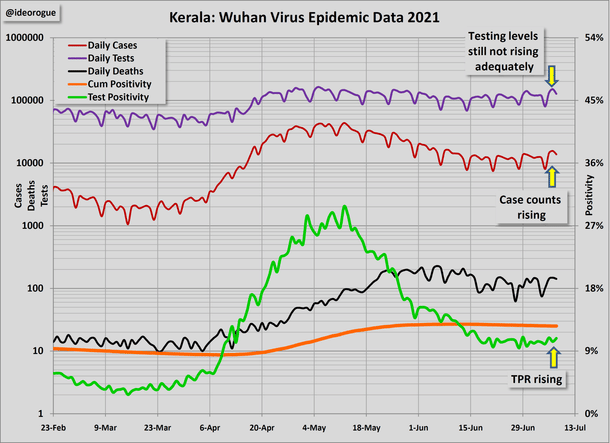

The gravest concern continues to be Kerala, where the Pinarayi Vijayan government has demonstrated a persistent inability to bring case counts and positivities down.

Today, Kerala accounts for a full third of all cases reported in the country. Worse, daily cases (red curve) and the TPR (green curve) are rising to dangerous levels, rather than declining. It is frankly shocking that the TPR has remained consistently above 10 per cent for over a month now. Consequently, the CP is in an abominably high plateau, and does not look set to decline to the requisite mark for months. And this precarious state of affairs is being dangerously prolonged, simply because testing, tracing and isolation are just not being conducted competently, at necessary levels. Perhaps it is not long before the state’s borders are sealed, and the Centre takes over.

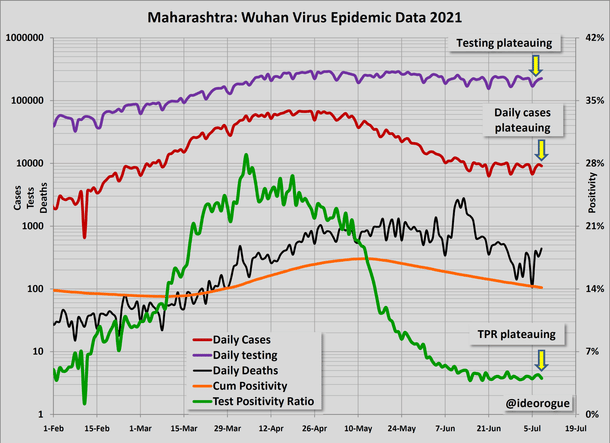

The situation in Maharashtra is equally grim. The only difference is that the TPR is much lower than it is in Kerala. However, with testing levels stagnating in Maharashtra, both daily case counts and the TPR are also unfortunately stuck on an ominous plateau. Indeed, the TPR has actually risen marginally this week, which means that the decline rate of the CP will only reduce further; and that does not augur well for either the state or the country.

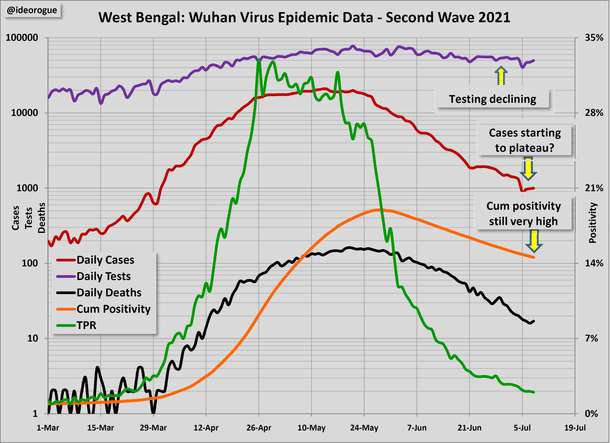

The third highest risk is posed by West Bengal. It may not seem so at first glance, since cases are down to about a thousand a day, and the TPR is at just 2 per cent. However, the biggest concern is a persistent decline in testing levels. It appears that the West Bengal government has chosen TPR as the principal monitoring parameter, rather than CP, and started to slacken off testing levels the moment TPR fell to around 5 per cent.

This is a mistake. As it is, testing levels in West Bengal have been woefully inadequate, which is why the peak of the second wave lingered there in a painful plateau for about a month.

The state’s leadership may argue in return that this is needless fussing, since the CP too, is declining consistently. In that case, they would do well to look at the chart below, and note two points: declining testing levels are causing both case counts and the TPR to plateau, while holding the CP at a dangerously-high level for simply too long. The focus should be on denying reproductive space to the virus, so that it doesn’t mutate too much; so the sooner the West Bengal government realises that, and ramps up testing to at least 1.25 to 1.5 lakh tests a day for starters, the less of a threat they will be to residents in their jurisdiction, and the rest of the country.

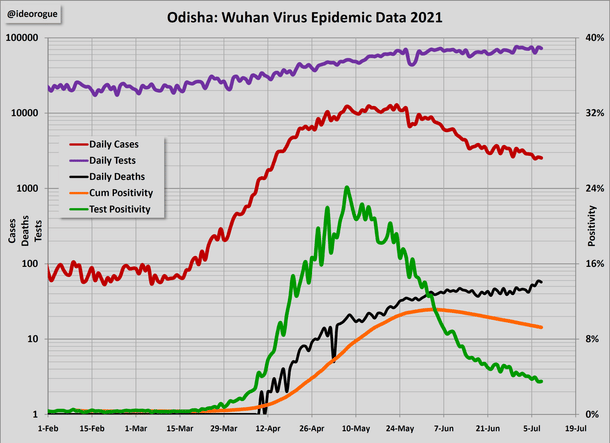

The fourth area of concern is Odisha. The risk emanating from there is of course not in the same league as Kerala, Maharashtra or West Bengal, but as the chart below shows, the current levels of daily cases, TPR and CP are too high for comfort, while their rate of decline is unacceptably low. Once again, the reason is inadequate testing. For proof, administrators from Odisha may review the chart below, and note how the slopes of the red and green curves decrease, in step with a plateauing of the purple testing curve. Still, the state has a few days in which to make amends, if they are to avert a resurgence.

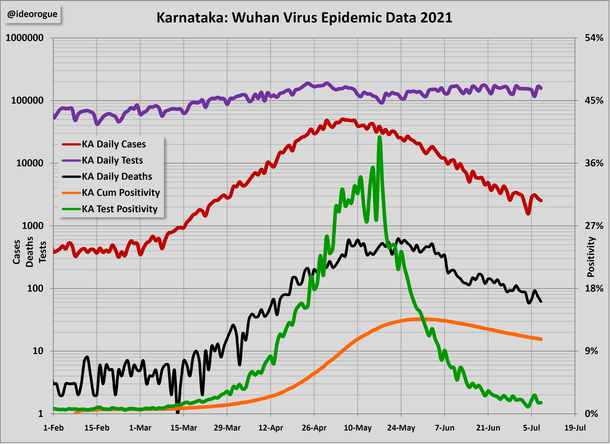

The fifth region of key concern is, surprisingly, Karnataka. Although both the TPR and daily case curves have been successfully bent, the cumulative positivity remains at an uneasy high of around 11 per cent. That means the epidemic is still simmering beneath the surface. Therefore, it would be prudent for the Karnataka administration to swiftly heighten monitoring, aggressively seek out vectors, push TPR below one per cent, and further hasten CP decline rates in the coming week.

Apart from these are the Northeastern states, where rising cases have pushed up the national tally. Here, terrain, logistics and remoteness are a real constraint in tackling the epidemic. The case counts may be small compared to large states, but they are gigantic when compared to the populations of the seven sisters. The TPR in Manipur is 16 per cent; in Sikkim it is 18 per cent; Mizoram reported over three hundred cases in the past 24 hours. And yet, the remedy is the same as for large states – aggressive testing, tracing, isolation and treatment. Size doesn’t matter.

Thus, the bottom line is that, the only way we can prevent a third wave, or at least stave it off, is by maintaining testing at peak levels, while the vaccination drive grinds on. Monitoring and inoculation have to move in tandem. So yes, there were severe bottlenecks in vaccine supply, which are now being gradually removed, but until the vaccine manufacturers come into their own, by August-September, the onus lies on the state governments, to maintain monitoring at peak levels, so that a nation-wide resurgence is inhibited.

In essence, the political leaderships in states of concern have to somehow understand that July 2021 is moving month in our battle against multiple variants of concern, and, that any slip ups now would not just undo public health security in one state, but have nation-wide ramifications as well.

All data from Covid19india.org.

Venu Gopal Narayanan is an independent upstream petroleum consultant who focuses on energy, geopolitics, current affairs and electoral arithmetic. He tweets at @ideorogue.