Ideas

Hoodbhoy’s Forbidden Love

Aloke Kumar

Apr 26, 2018, 04:32 PM | Updated 04:32 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

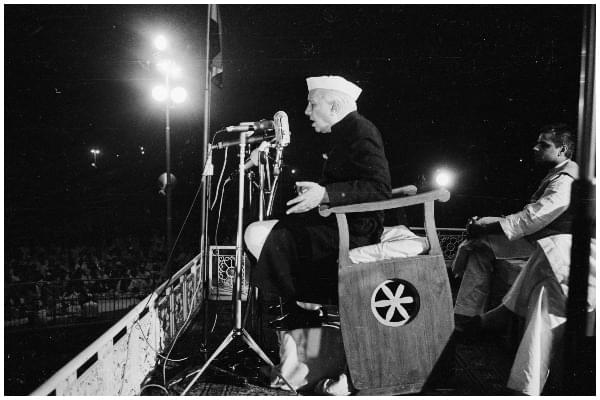

Pakistan was born in 1947, while Bharat, that is India, achieved Independence that year. When Pervez Hoodbhoy declared that if it had not been for Jawaharlal Nehru “India would have become a garbage dump for every kind of crackpot science” this simple, yet subtle truth did not resonate with him. His essay is essentially a political piece about his love for Nehru and hatred for Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)/Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). While discussing his political preferences, Hoodbhoy conflates two entities – the Republic of India, born in 1947 and Bharat, a continuum existing for millennia. It is in trying to make this leap that Hoodbhoy stumbles and falls into the abyss of pitiful scholarship.

My response to Hoodbhoy’s essay is not meant as a partisan piece. I am not interested in disparaging or defending anyone simply due to their location in the political spectrum; I recognise contributions from Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, a man deserving accolades for laying the foundations of some of India’s finest institutions. Rather, my essay is meant to defend the eons long tradition of passionate scientific enquiry that the Bharatiya traditions have supported.

A human being is not simply a collection of sinews and bone. While the material body forms the tangible structure of this ape-descendant, the consciousness remains an intangible aspect of the person. In a sense, consciousness remains intangible since its effect is so all encompassing it cannot easily be measured in words. Similarly, brick and mortar buildings, instruments and bylaws form the external structure of scientific institutions, but its spirit is formed by intangible emotions generated through the quest for knowledge and ability to constantly question. It is this intangible spirit of seeking that flows through Bharat like an invisible Ganga.

You see, unlike Pakistan, Bharat has a millennia old tradition of scientific temperament, a tradition which flows into our philosophy, into the Indic ‘religions’ and into our way of life. From the discovery of shoonya (zero), to that of ayurveda (natural medicine), to the Kerala school of mathematics, passionate scientific inquiry is our tradition. To 'dump' this millennia old legacy on a singular person demonstrates a lack of understanding of the depth of our 'infidel' tradition(s).

If a singular person is responsible for all the spirit of scientific enquiry today in this country, then the state of science in pre-1947 India should have been terrible, perhaps similar to the state of science in Pakistan today. Instead, pre-independence India was towering with personalities who stood shoulder-to-shoulder with the giants of science. Pre-independence India produced giants like Srinivasa Ramanujam (1887-1920), who will forever be remembered as ‘the man who knew infinity’ for his amazing work in mathematics. This time-period also produced Sir J C Bose (1858-1937), whose discoveries of radio and crescograph were decades ahead of his peers. We had Satyendra Nath Bose (1894-1974; seminal paper 1924) after whom half our universe is named. While Bose himself never received the Nobel prize, at least two Nobels (1997 and 2001) were awarded for work on the Bose-Einstein condensate, proving the excellence of his landmark contribution to physics. Sir C V Raman (Nobel Prize – 1930) needs no introduction; virtually every Indian child knows about the Raman effect and has been in some way inspired by his story.

We empowered personalities like Sir Upendranath Brahmachari (1873-1946), who saved millions of lives through his research in the area of medicine (kalaazar to be specific). Luminaries like Meghnad Saha (1893-1956), Prasanta Kumar Mahalanobis (1893-1972) and Acharya Prafulla Chandra Ray (1861-1944) walked on our pavandharti (holy land) before India knew freedom. An exhaustive list of eminent scientists who performed seminal work would make this paragraph too long and I do not feel I can do justice to this great scientific lineage. Modern India has reaped enormous benefit through the institutions created by Nehru and these places have produced extremely distinguished scientists and impressive technology. However, the spirit of inquiry that resides within the walls of those institutions is much older than the brick and mortar of our current institutions.

The Bharatiya way of life, unencumbered by the concept of blasphemy, has always supported critical questioning and the power of observation. It is no co-incidence that even the knowledge of the creator is questioned in Rigveda’s Nasadiya Sukta. This freedom to question informs us either consciously or subconsciously. One eminent scientist who made his inspiration clear was Acharya Prafulla Chandra Ray. He was adistinguished scientist, soul, entrepreneur knowledgeable in the shastras. He founded Bengal Chemicals and the author of A History of Hindu Chemistry. In his book, the acharya discusses leaps in Rasayana Shashtra (Chemistry) in India. Acharya begins his discussion with Atharva Veda and continues to discuss the various advances in chemistry as documented in our shastras.

But let us get back to the present. Are our institutions being washed away by a deluge of gomutra (cow urine), as some Naxalite rags will have us believe? Or is the commitment to institution building still intact and going strong? Post-2014, two new Indian Institutes of Science Education and Research (IISERs) have been established - IISER Tirupathi in 2015 and IISER Behrampur in 2016. IISER Nagaland was also announced in the 2015 Budget. In 2016, the Union cabinet approved India’s participation in the LIGO project, through a LIGO observatory in India. LIGO is possibly one of the most interesting large-scale scientific endeavours of our species till date and it is heartening to see the political dispensation’s understanding of its importance.

Other than institution building, post-2014, we have continued to see a strong support for scientific research through various programmes. IMPRINT is a unique initiative to bring academia and industry together on one platform so that knowledge may flow from the labs to the real world and vice-versa. Another popular initiative is the GIAN initiative, which brought world-renowned researchers to India to enable a virtuous cycle of collaboration and scientific exchange. These are just some examples of the positive steps that have been taken to strengthen the scientific institutions and programmes in our country.

However, we must remember that governments can only build and strengthen our institutions and it remains a life-less object if not infused with the scientific spirit. For Bharat, this spirit emanates thousands of years into our past and in our heritage. Our heritage remains our inspiration. Our heritage is who we are.

For someone from Pakistan, whose umbilical cord to this long tradition was severed in 1947, it is but natural to view the entirety of India’s progress through the small time-scale of the past 70 years. There is no doubt that this umbilical cord has been fully severed. Perhaps the greatest export of this continuum of our scientific quest is yoga, and its worldwide impact can be gauged by the sheer enthusiasm with which International Yoga Day is celebrated. The idea to institutionalise this day was proposed by our current Prime minister, Narendra Modi, to the United Nations in 2014. The bill was co-sponsored by an overwhelming 177 UN countries. Do you know which countries abstained? No prizes for guessing. Pakistan, along with countries like Saudi Arabia declined to co-sponsor the proposal. Did Pakistan abstain simply because along with Nyaya, Vaiseshika, Samkhya, Purvamimamsaand Vedanta, Yoga is one of the six schools of Hindu darshanic thought? This question is for the Pakistanis to ponder and answer.

The common man’s life is not informed by the Constitution so much as it is by his/her cultural immersion. This culture is often a sub-conscious long-range force which inspires the human ensemble’s way of life. Our culture has never discouraged questioning. Where else would you find religious texts like Nasadiya Sukta and Upanishads? I do not care much about Hoodbhoy’s forbidden love affair with Nehru, but only know that the credit for this culture cannot be ascribed to any politician be it Modi or Nehru. It has been shaped by thousands and millions of luminaries who continue to illuminate our lives even though they have long passed away.

Dr Aloke Kumar is currently an assistant professor at the Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore.