Ideas

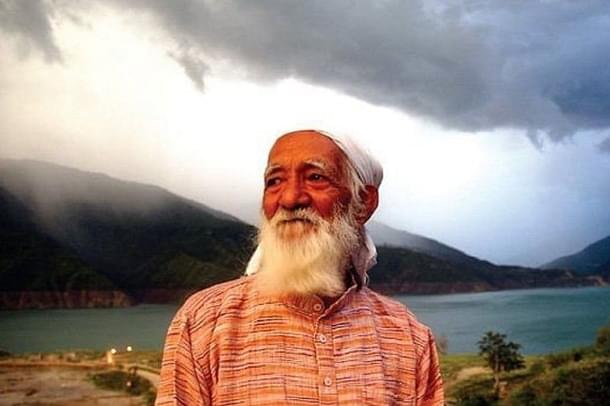

Sunderlal Bahuguna (1927-2021): Whose Ecology Flowed From His Dharma

Aravindan Neelakandan

May 22, 2021, 09:23 AM | Updated 09:20 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Between December 13 and 20 of 1977, the Indian press was flooded with reports of a new kind of movement. In the Advani forest of the Henval ghati region of present-day Uttarakhand, women in large numbers were hugging and protecting the trees of the forest. The women had organised, among other cultural activities, reading from the Bhagavad Gita and the Srimad Bhagavata.

Women narrators of the divine lore of Srimad Bhagavata Katha reinforced religiously in the minds of the listeners the spiritual centrality of the forest to Indian spirituality. The entire enchanting life of Sri Krishna and His adventures have always taken place in forests and fields adjoining the forests.

The protest now famous worldwide as the Chipko movement was an uniquely Indian environmental movement. It was a people’s movement. It was a green protest not of the Western variety with alien ideologies but a spiritual protest movement.

The man behind the movement was Sunderlal Bahuguna.

A Gandhian working in the Himalayan villages, he understood the importance of forest to the lives of the villagers. From the colonial government to the post-independent government, the state had followed the mechanistic path to development which gave little value to nature.

In the West meanwhile the environmental movement was beginning. With the agenda of saving the thickness of the egg membrane of eagles from DDT, it seemed distant and aloof.

In the USSR, any talk of environmental protection was a sure invitation to a KGB midnight knock and an assured ticket to the Gulags in Siberia.

In such a global environment, Sunderlal Bahuguna in 1973 spoke of the importance of protecting the forest and linking them to the livelihood of mountain villages and ensuring that vulnerable human communities are safe from imminent ecological disasters.

Sunderlal Bahuguna personified an ecological movement for a developing, post-colonial country; a movement that derived its strength from the spiritual culture of the people. In his demise, we have been left with an inspiring life and nebulous thoughts for the making of a vibrant Hindu environmental vision.

Walking more than 5000 kilometres on foot, he took his message to the people. Padayatras have always been a traditional way of reaching out to people – not in the spirit of propaganda and proselytising but as a means to Jana-Darshan, to learn from the people with humility – how people live and sustain themselves economically and spiritually and ecologically.

Sunderlal Bahuguna successfully showed how important it is to incorporate environmental protection as part of the developmental process and how environmental movements can derive their strength from the natural, spiritual traditions of Sanatana Dharma. He explained:

The story of Lord Krishna is very popular in India. We have one week’s programme in which the whole story is recited and people come with great devotion bringing offerings of rice, vegetables or fruits - that was the old system. What we did was to explain the whole story in terms of three things: your relationship with your inner self, with society and with nature.

… Religion amongst the people is so powerful. We organise the people, educate them and collect a handful of rice from each family - that means the involvement of each family - and people take a pledge to work for our cause and so it goes on. There are people in India who are very devoted to religion and that is the secret of success of the Chipko movement. We tried to interpret religion in its real sense. Ritual has done so much harm to religion in India that people have forgotten the real spirit of religion. The body is there, but without any heart. We have to revive the real spirit of the religion. This is what we did in Chipko movement.

Here is an instance of how Bahuguna employed Puranic imagery to inspire his fight against pollution:

The Yamuna River, where Krishna bathes, is something living, she is loved by Krishna too. When the many-headed poisonous serpent Kaliya came and polluted the Yamuna with his venom, Krishna drove him away. And who is this Kaliya? He represents the pollution of our present day! Kaliya was polluting the river, and by that had become a nuisance for the whole society, for everything. This pollution is the Kaliya snake and every citizen has to play the role of Krishna today. That means you have to become like Krishna - a lover of all life; at one with the universe. Until you become ‘Krishna’ you cannot save this river from being polluted; you cannot save this world from being exploited by the demons like Kaliya.

Sunderlal Bahuguna had taken long fasts during his environmental protection movement. But he was careful not to 'secularise' it in the reductionist sense of the term.

He emphasized that the fast was not a hunger strike, but an act of devotion.

This is from a man who in May 1995, went on a fast for 45 days against the Tehri Dam construction. The man who made the then Prime Minister of the nation assure him that a complete review of the Tehri dam project would be undertaken and in less than a year's time when the assurance of the PM was not kept, Sunderlal Bahuguna undertook a fast for 74 days. In his own words:

Here you believe that there is God inside everybody. And so you pray to the God to awaken the God inside him to make him realize that he is making a mistake.

Today, a protest movement against every development project in India would likely have its strings being pulled from outside of India.

However, not every protestor is a traitor. There are many complex forces in play in a pluralist democracy like India. That is a reason why India needs a genuine green movement with its roots strong in India’s core spiritual values.

With climate change creating uncommon events in the form of excessive rains, floods, frequent cyclones and prolonged droughts, an enlightened, holistic environmental activism and understanding of ecological problems become important for any civilisation.

With powerful and independent organisational resources and an ecologically sound value system within, Hindutva is in a position to evolve an indigenous environmental movement that combines science, spirituality and environmentalism. Bahuguna himself had explained the kind of workers the movement needs and again this reflected a vision rooted in the spiritual tradition of India:

Young people are needed who have hearts full of compassion and creative minds to find out the solutions and hands which are ready to serve. We need to bring three types of people together in small groups wherever they are. First are humanitarian scientists, who will use their knowledge to mitigate the miseries of human beings and mother earth. Then social activists who are impatient to bring a change through non-violent means. Third are compassionate artists, musicians, journalists and literary men and women. These three types of people should come together in small groups and find out the solutions to the problems. These three people are the symbols of three basic principles of the Gita - knowledge, action and devotion - jnana, karma and bhakti. Action, karma, is the way to communicate to the people - you must become the symbol of your thoughts and ideas - but the most important element is bhakti, devotion.

The above words of Bahuguna, whether one accepts all his worldviews or not, should be an arousing call to Hindutvaites, both thinkers and activists -fortunately the movement of the Sangh has no such distinction- to create a powerful India-rooted environmental movement.

That shall be the real honour we can bestow upon the sacred memory of this great soul.

Aravindan is a contributing editor at Swarajya.