Ideas

What Does Differential Wage Growth Tell Us About The Future Of Work In India?

Abhishek Patil

Mar 31, 2021, 11:57 PM | Updated 11:57 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

India, after liberalisation reforms, has seen consistent economic growth and diversification, leading to increased employment and growth in wages. During this period, technology adoption in Indian industry and influx of foreign technology has increased too, as the economy opened up for global capital and import of foreign technology.

These factors have induced fundamental changes in India’s labour dynamics.

(Under)Employment & Economic Productivity

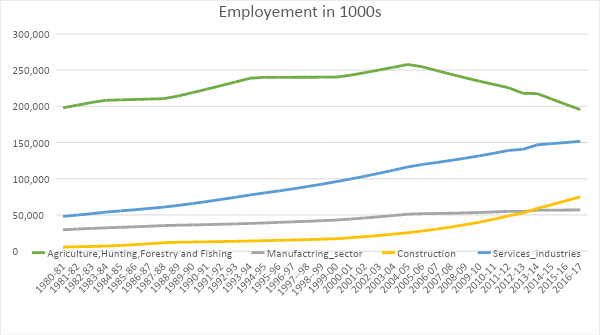

Indian labour has always been agrarian in nature. Agriculture employs more people than any other sector even today. Liberalisation of the economy in the 1980s showed early signs of de-agrarianism of Indian labour, and by the early 2000s, the number of people employed in agriculture started declining.

This decline has become rapid now, and the labour moving out of agriculture is getting absorbed into the services and construction sectors. Hardly any of this labour has been absorbed into manufacturing because Indian manufacturing has become capital-intensive due to the infusion of new technology. Employment generation in the sector has also been near-stagnant.

Most of the labour migrating from agriculture is unskilled, whereas manufacturing employment demands skilled labour.

Employment growth by sectors 1980-2017

A study found that at the peak of de-agrarianising Indian labour, which is 2011 to 2015, the number of people employed in agriculture was reduced by 26 million. On the other hand, 33 million new jobs were added in other non-agrarian sectors, mainly in services and construction. The number of people employed in agriculture has reached pre-1980 levels in actual numbers, showing a significant sign of de-agrarianisation of Indian labour.

Liberalisation has led to an exponential outburst in the productivity of the Indian economy. It has been the services sector period, which has absorbed new labour, generating new jobs and yielding a higher output in the process. Agriculture, which was left out of economic reforms, continues to be the least productive while employing the highest number of the working population.

Manufacturing, which has become capital-intensive, employing the least working population, has also seen very high productivity after the economic reforms.

Gross output of sectors 1980-2016

This graph also shows the divergence between the sectors in their outputs, that is, the manufacturing and services sector, which saw reforms, grew their output exponentially high. In contrast, agriculture and construction continue to lack growth and value addition even today.

To point out the structural changes resulting from economic reforms, while the Indian labour force is still largely agrarian, we’ll further see a radical decline in the number of agriculture workers. It is also obvious that labour in agriculture is under-employed, so it is imperative to de-agrarianise labour, facilitating the migration of labour from agriculture to other sectors and bringing liberal reforms in agriculture to increase its share of productivity.

Technology-induced Dynamics

Data from the National Sample Survey shows that the average weekly earnings of the Indian worker increased by Rs 800 during the period from 2005 to 2012. The increase in wages may be higher than the average for some high-skilled workers, while it may be below-average for low-skilled or unskilled workers. The overall wages, though, have increased for everyone in this period.

However, a closer look at the pattern of wage growth shows a new trend of polarisation – the rate of wage growth is faster for high-skilled and low-skilled workers, while for mid-skilled workers, it is relatively slow.

In 2005-06, we noticed wages ages across occupations were closer to the average wage. But by the year 2011-12, wages are seen to be getting polarised with occupations. While all trades earn more than ever, the wage growth rate for high-skilled and low-skilled workers is higher, and the wage growth for mid-skilled workers is lower.

For example, the wage of a high-skilled worker like the architect and a low-skilled worker like a gardener grew much faster in the period 2005-06 to 2011-12. But the wages of a mid-skilled worker like the freight operator grew comparatively slowly.

Wage distribution across occupations during 2005-06 and 2011-12

In the graph on the left, showing the wage distribution across occupations for the period 2005-05, the dots are tightly distributed, close to the average red line and more horizontally aligned. On the right, for the period 2011-12, the dots along the centre are sparse and become more vertical, indicating that the wages are increasingly polarising.

Lately, polarisation is commonly occurring across every economy, and it will only become more pronounced in the age of automation. The polarisation can be explained by the effect of technology on labour.

Mid-skilled jobs are repetitive, which can be easily codified to be done by a robot. High-skilled jobs are considered non-repetitive abstract and low-skilled jobs as non-repetitive mechanical, requiring some form of human intervention to carry out these tasks. Being non-repetitive makes the job harder to be codified and has kept it immune from automation technologies, at least for now.

So, we will increasingly notice a high demand and fast wage rates for high-skilled and low-skilled workers. Mid-skilled jobs and their wages will decline as new technologies such as artificial intelligence and 3D printing intensify.

Future of Work in India

The Indian labour dynamics have altered fundamentally in the past three decades. The labour is de-agrarianising rapidly, and jobs and wages are polarising. These trends will continue more aggressively in the future as we move towards the fourth industrial revolution, with the advent of more advanced technologies like AI, 3D printing and the Internet of Technologies, which will bring further disruption to labour dynamics.

India, at least in theory, seems to be getting it right. Better wages and employment for Indian labour will precariously depend on the convergence of three factors – the country’s ability to industrialise, build infrastructure, and bring in agriculture reforms.

India is showing a solid intent to industrialise. The recent labour reforms, new production-linked incentive schemes, the rapid expansion of rail and road infrastructure, and agriculture reforms – which can mobilise under-employed agriculture labour to other productive sectors – indicate an overall political willingness to mobilise resources and labour from agriculture to industry. However, some of these reforms have been politically unpopular.

The introduction of new disruptive technologies will bring a whole new form of creative destruction to labour dynamics, unlike anything seen before. Coupled with the growing entrepreneurial spirit and new consumption patterns, which are constantly evolving, new jobs, skill sets, products, and even industries will emerge.

We don’t know what the future of work will look like. Some predict a dystopian “End of Work” future where robots take over jobs, leading to mass unemployment and civil unrest. And there are utopian “Free of Work” predictions too where we will reach a post-scarcity world. In this latter scenario, robots will produce everything for humans. There won’t be any menial labour, and we can finally enjoy life to the fullest without worrying about work.

The future is likely to fall somewhere between these two extreme predictions and continuously lean one way or another from time to time, often giving uncertain shocks to labour. Therefore, we cannot skill or educate labour for some ‘deterministic’ future of work. So, labour policies should be devised to keep the labour markets and nature of employment flexible enough to adapt to this disruptive future of work.