Infrastructure

How India Is Finally Turning This Nicobar Island Into A 'Great' Asset

Prakhar Gupta

Dec 09, 2024, 03:41 PM | Updated Jan 22, 2025, 10:51 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Last week saw the conclusion of a historic auction — India's first-ever allocation of offshore critical mineral blocks. A total of 13 blocks were put up for bidding, marking a significant step in India’s mineral development sector.

For nearly two decades, offshore mining hadn't made progress, despite the Offshore Areas Mineral (Development and Regulation) Act, 2002 being in place.

Headline writers had it easy this time, with the novelty of the auction being the perfect hook: India’s inaugural auction of offshore critical mineral blocks.

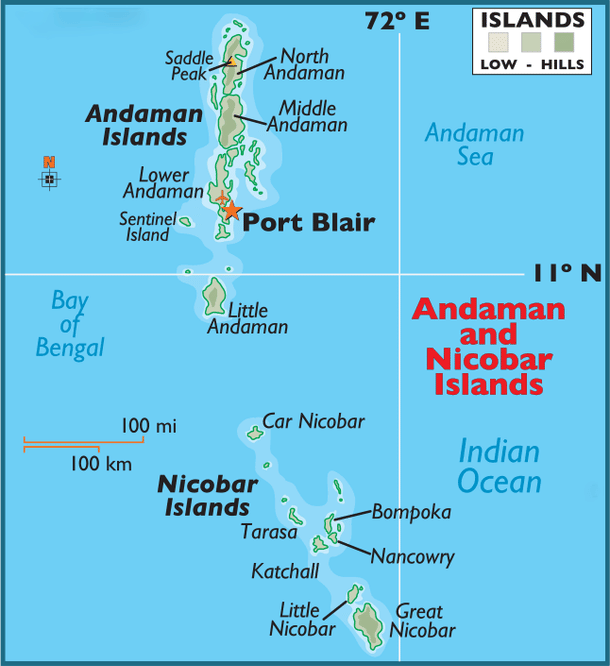

The milestone dominated the coverage, but there’s a lesser-discussed yet equally noteworthy detail: seven of these 13 blocks lie off the coast of the Great Nicobar Island.

This island, the largest and southernmost in the Nicobar group, has long been identified as an asset. But in recent years, it has increasingly been in the spotlight as its prominence in India's strategic calculus has grown steadily.

Historically, maritime powers have leveraged the Andaman and Nicobar Islands to project influence across the Indian Ocean, and as strategic bases for eastward expeditions. Rajendra Chola I of the Chola dynasty was among the first to exploit their geo-strategic advantage. The Cholas, with their formidable navy, used the islands as a springboard for their expansion into Southeast Asia. After conquering modern-day Sri Lanka, they used the Andamans to launch raids on the Srivijaya empire's ports in present-day Indonesia.

While the islands have long been recognised for their strategic importance, discussions have predominantly emphasised their military significance, particularly their proximity to the Malacca Strait, a vital maritime chokepoint.

However, their strategic importance has historically been driven by the economic rationale of securing resources, protecting trade routes, and expanding trade networks, beyond just military dominance.

Tamil historian KA Nilakanta Sastri suggested that Srivijaya’s attempts to curtail Chola trade with China may have been a catalyst for the Chola-Srivijaya conflict, an episode that reshaped Southeast Asia.

This economic rationale, long rooted in history, is once again becoming relevant in the modern context, where it aligns with broader strategic considerations.

The Andaman and Nicobar Islands serve as a critical link between the western Pacific Ocean and the Indian Ocean region. The territory is positioned along one of the world’s busiest sea lanes of communication (SLOCs) — the Prepares Channel to the north, the Ten Degree Channel between the Andaman and Nicobar groups, and the Great (or Six Degree) Channel south of Great Nicobar Island. While the Prepares and Ten Degree Channels are less frequently used by commercial shipping, most vessels transiting the Malacca Strait pass through the Great Channel.

The Great Channel, separating Great Nicobar Island from Indonesia's Aceh Province, is deep and clear, making it navigable for large merchant vessels.

Located at the western edge of the Malacca Strait, it serves as a convergence point for three major maritime routes originating from or heading toward the Cape of Good Hope, the Gulf of Aden, and the Straits of Hormuz. This convergence results in high shipping density, raising the risk of disruption. The significance of the Malacca Strait lies in the fact that it provides the shortest maritime route between the Indian Ocean and the Pacific.

While alternative routes such as the Sunda, Lombok, and Ombai-Wetar Straits exist, they entail longer voyages and, thus, higher costs. As a critical feeder and outlet for the Malacca Strait, the Great Channel is vital for maintaining the flow of maritime traffic between the Indian Ocean and the western Pacific Ocean. Any disruption here could effectively block access to the Malacca Strait.

It is here, at the southern tip of Great Nicobar Island, straddling the Great Channel, that India is developing a container transhipment hub.

For decades, India’s maritime logistics have been hindered by inadequate infrastructure at its ports, compounded by insufficient draft depths at berths and channels. At the same time, the size of global vessels has grown significantly over the past decade, with most major shipping lines now preferring ports that offer a minimum draft of 18 meters.

As a result, the availability of sufficient draft has become a critical factor in attracting shipping lines. Ports in southern India, such as Cochin and VO Chidambaranar, are constrained by draft depths of 14.5 metres and 14.2 metres, respectively.

Hence, vessels with large tonnage are unable to dock at Indian ports. Consequently, large container ships carrying cargo destined for India are required to offload at nearby transhipment ports. From there, the cargo is transferred to smaller feeder ships that can access Indian ports. This has led to ships carrying consignments for India docking at transhipment hubs such as Colombo in Sri Lanka, Jebel Ali in Dubai, Klang in Malaysia, and Singapore, rather than Indian ports.

In contrast, regions like Vizhinjam, Kanyakumari, and interestingly, the Great Nicobar Island, offer potential deep drafts of around 20 meters.

The East-West Shipping Corridor handles a large share of global container traffic, serving as a key route for mainline vessels transporting cargo between the US, Europe, and Asia. Shipping companies prefer transhipment ports that require minimal deviation from their established routes. However, India’s ports on the East and West coasts are situated over five hours’ sailing distance from this critical shipping lane, making them less appealing for transhipment compared to Colombo, which lies just 0.5 to 1 hour away.

The Great Nicobar Island, however, presents a promising option due to its position approximately 10 nautical miles (or 0.5-1 hour) off the Suez route.

Currently, nearly 75 per cent of India’s transhipped cargo is handled at ports outside India. Colombo, Singapore and Klang handle more than 85 per cent of this cargo. Nearly 45 per cent of this cargo is handled at Colombo Port alone.

India needs transhipment ports that can compete with international counterparts in terms of location, draft, and overall cost efficiency. This is crucial for several reasons.

Currently, Indian ports lose approximately $200-220 million in potential revenue each year due to the transhipment of cargo originating from or destined for India.

The loss is even greater when factoring in the untapped opportunity to handle cargo from neighbouring countries. A transhipment hub at Great Nicobar Island could attract large ships carrying goods for Bangladesh and Myanmar, which currently rely on ports like Singapore and Malaysia.

In 2015, nearly 70 per cent of cargo from Bangladesh and Myanmar was routed through Singapore. With Great Nicobar closer to both countries, much of this traffic could shift there. The shorter distance for feeder ships would save both time and money, making it a more cost-effective alternative.

In addition to the revenue loss, inefficient logistics take a toll on a significant portion of India’s EXIM (export-import) industry, especially in southern India. The extra port handling charges at transhipment hubs add to logistical inefficiencies.

For example, transhipping cargo through international hubs like Colombo and Singapore adds an additional cost of approximately $80-100 per TEU (Twenty-foot Equivalent Unit, the standard size for shipping containers). This extra cost could be avoided if the cargo were directly imported or exported through Indian ports instead.

India’s reliance on international ports for 75 per cent of its transhipment cargo exposes the country to grave risks. This dependence makes Indian industries vulnerable to political crises, rising costs, inefficiencies, and congestion at foreign ports, all of which could undermine the long-term competitiveness of India’s trade as exports grow.

The allocation of mineral blocks near Great Nicobar Island further strengthens the case for its development. Located in the Andaman Sea on the West Sewell Ridge, east of the island, these blocks are rich in polymetallic nodules and crusts. These materials contain valuable minerals such as manganese, nickel, cobalt, and copper — key components for the green energy transition, used in electric vehicle batteries and wind turbines.

There are military imperatives too, of course.

A large port in the Greater Nicobar Island, even if primarily civilian, could serve as a key logistics hub for the Indian Navy, especially in the case of a crisis. In the not-so-distant future, the port could enable the Navy to establish a more consistent presence in the Western Pacific, a region it currently only makes occasional forays into.

In the northern part of the island lies INS Baaz, a naval air station set for a runway upgrade to support P-8I anti-submarine aircraft. Their prey — Chinese submarines — have already been spotted near the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

The Chinese have long been interested in this region, mainly because of its proximity to maritime chokepoints that control access to the Indian Ocean from the Western Pacific. These passages are crucial not only for commercial shipping — vital for its trade — but also for its military vessels, including submarines, which use them to enter the Indian Ocean.

In recent years, Chinese survey ships have been spotted just south of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, conducting extensive surveys around the Ninety East Ridge. This prominent underwater feature, a volcanic ridge running north to south along the floor of the Indian Ocean, lies near key chokepoints — routes heavily used by Chinese military vessels, including submarines. The area around the Ninety East Ridge is challenging for submarine operations, as it represents a long stretch of shallow waters, which can pose a risk for submarines due to the higher likelihood of detection.

Chinese vessels have repeatedly mapped this region in a ‘lawnmower pattern,’ indicating that they are conducting detailed bathymetric surveys to map the depth of the ocean floors, study the ocean environment and collect hydrological data.

With such surveys, China is trying to place the pieces necessary for an increased PLAN presence in the Indian Ocean over the next decade. This information is crucial for China’s efforts to monitor submarine movements in this region and to map safe, undetectable routes for its own submarines.

In September 2019, India had to expel a Chinese research vessel operating in its exclusive economic zone around the islands, just west of Port Blair, without permission.

China now has a base at Cambodia's Ream naval facility, near the eastern edge of the Indian Ocean, featuring a pier nearly identical in size to the 363-metre-long pier at its base in Djibouti, capable of accommodating China’s largest aircraft carrier.

This will only expand China's military footprint around the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, making it all the more important for India to increase its presence in these waters. There's no better way to achieve this than by underpinning the presence through economic development on Great Nicobar Island, and with the upcoming transshipment hub and the allocation of mineral blocks already underway, it seems those in New Delhi looking at this issue have finally come around to the same realisation.

Prakhar Gupta is a senior editor at Swarajya. He tweets @prakharkgupta.