Infrastructure

Kerala’s Plan To Fight Power Shortage Is Remarkably Short-Sighted

Ananth Krishna

Mar 29, 2017, 09:28 PM | Updated 09:28 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Even as India has become a net exporter of power for the first time, Kerala is staring down a power crisis that it doesn’t have answers for in the long run. Government of Kerala had decided to restart the controversial Athirappilly Hydel Power Project to rescue the state from the crisis, but this is not nearly effective, as the generation capacity of the project is too small to have an impact on the power sector in the state.

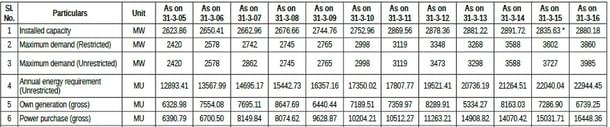

The deficiency of power in Kerala is not insignificant; more than 70 per cent of the state’s power comes from outside the state. The capacity addition is disproportionate to the rise in demand for the same (as illustrated in Table 1).

While the annual energy requirement in the state has nearly doubled from 12,000 million units in 2005 to 22,000 million units in 2016, the addition of electricity has increased a mere 411 million units. This stands in stark contrast to Gujarat, where the power capacity rose from 8,974 MW in 2004 to 23,887 MW in 2013 (a 166 per cent growth), turning it from a power-deficient state to a power-surplus one (For comparison, Kerala generated 2,600 MW in 2005 to 2,880 MW in 2016, an increase of 1 per cent).

The state government has highlighted the Athirappilly Power Project as essential to combat this situation, but the modest addition of 144 MW from the project is, ultimately, insignificant. The power minister, the controversial Communist Party of India (Marxist) leader M M Mani, has stated that the state needs both big and small hydel power projects to tide over the crisis. Examining the proposals mooted in the budget and the ones in progress, one can, however, conclude that the state will still have to reckon with a crisis, the projects only alleviating it to an infinitesimal amount.

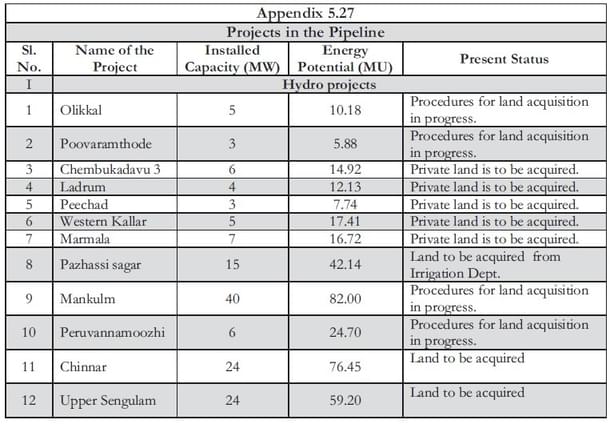

As detailed in the table below, the total addition of all projects that the Kerala State Electricity Board (KSEBL) has proposed will add a mere 142 MW to the grid. The budget has proposed the addition of 15 new small hydroelectric projects, which will add another 93 MW to the grid, which are to be completed at a cost of Rs 265 crore.

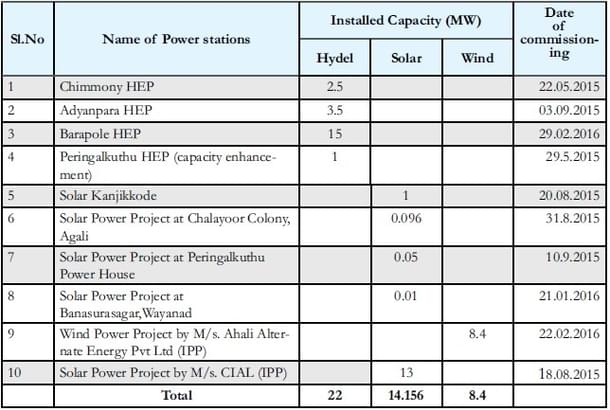

If we are to compare the additions that occurred during 2015-16 (Table 3), one can see that the increase is a welcome one but ‘not nearly enough’.

As an example of how these projects come about, let’s look at the largest of the listed projects, the Barapole project. Initiated in 2010, its generation capacity was reduced from 21 MW to 15 MW when the Supreme Court ordered that the project should not affect the area of the Rajiv Gandhi National Park in Kodagu – as a result, a “trench weir system” was created to not affect forest land in Karnataka. The total cost of the project was Rs 136 crore, and it adds a mere 36 million units to the grid. But considering the state’s condition, any small addition is welcome.

Another issue that has bogged down the KSEBL is employee productivity. According to the Planning Commission, in an assessment made in 2011-12, while employees have declined by 32 per cent in other state power utilities (as a whole), the number has increased by 30 per cent in a similar time frame in KSEBL. (Fingers can be pointed at the system of welfare employment, especially in the context where recruitment has been done superseding Central Electricity Authority's guidelines.)

In a way that mirrors the Kerala State Road Transport Corporation’s 7.2 employees per bus mandate, KSEBL employees 1.92 employees per million units of electricity sold, compared to the national average of 1.12. If we are to make a more honest assessment, the company employs 5.45 employees per million units generated! All this obviously amounts to spending a higher proportion of expenditure on its employees; 27.2 per cent of total expenditure is on wage/salary, compared to a 9.7 per cent average nationally. (Statistics for 2011-12, the proportion of expenditure to employees for KSEBL, 2015-16 is 26.8 per cent.)

Just recently, trade unions opposed the restructuring of the company by reducing senior assistants to a third of the current number and increasing the proportion of contract employees as a cost cutting measure, as suggested by a team from Indian Institute of Management, Calcutta.

The state depends heavily on hydroelectric projects, constituting approximately 70 per cent of the state’s internal generation. This sort of dependency results in electricity shortages every year during summer as water levels recede in reservoirs.

The state has dealt with the deficiency by ramping up inter-state power purchase. One can clearly see how the state has ramped up purchase from 6,800 million units in 2005 to 16,000 million units in 2016 as the demand for power increased (Table 1). The power purchases costs the state a fortune; the KSEBL spent Rs 633,681.62 lakh to purchase power last year, which amounts to almost half of total expenditure incurred by the company.

The state continues to plan power purchase agreements. While this by itself will alleviate the problem in the short term, no long-term solution has been mooted, nor is it the subject of any public discussion. A series of stop-gap and short-term solutions will not work for the state, especially as consumption rises. The company’s burden will continue to increase as time progresses, and its ability to charge the consumer a fair price is limited by the regulatory commission, which has long been averse to fare hikes.

All this while the company has made an operating loss of Rs 313 crore for the financial year ending 2016.

The KSEBL and the ministry need to show some tact and zeal in combating the power crisis and not find a short-term solution that may be easy but financially burdensome. It needs to encourage independent power producers to set up shop – have equitable fare charges, and cut employee costs. Another suggestion that can be put forth is to invest in thermal or renewable energy producers outside the state, since Kerala has high population density, and acquiring land inside the state is an arduous process.

The state may very well have an effective modern transmission system and be close to achieving 100 per cent electrification, but without a long-term sustainable plan for combating the crisis, it is surely doomed to be in darkness.

Ananth Krishna is a lawyer and observer of Kerala's politics.