Magazine

Aren’t Shrimps Vegetables?

Ramananda Sengupta

Jun 05, 2015, 08:47 PM | Updated Feb 11, 2016, 10:06 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Memories of a visit to China with President K.R. Narayanan in 2000, marked by a communication gap that still hasn’t narrowed

“May I get something vegetarian, please?” Rajya Sabha MP Sushma Swaraj asked a liveried attendant as we waited for the evening to begin.

“Of course, right away,” beamed the young lad as he scurried off.

He returned moments later, proudly bearing a tray of assorted shrimps.

“But I asked for something vegetarian,” said the startled MP.

“Yes, yes! Vegetables from the sea!” stammered the young lad, his beam turning into bewilderment.

Beijing, Monday, 29 May, 200o. We landed to a ceremonial welcome in Beijing a day earlier aboard Air India One, the Boeing 747 ferrying the President of India, Kocheril Raman Narayanan, on his official visit to China. His near-250 -strong entourage included bureaucrats, members of parliament, diplomats, support and security staff, and journalists like me.

We were assembled at the Great Hall of the People, awaiting Presidents Narayanan and Jiang Zemin at the formal banquet. The fact that the magnificent feast that followed had no vegetarian dish—bar ‘Diced Rolls of Bean Curd”—didn’t faze the sporting Ms Swaraj, who reportedly lived off the fresh fruits served at meals for the entire week-long trip. The meal was followed by a concert featuring Dr L. Subramaniam and the Beijing Symphony Orchestra.

President Narayanan—who in 1976 went to Beijing as India’s first ambassador after the 1962 border war—was back to soothe ruffled relations caused by India’s nuclear tests of May 1998. Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s letter to US President Bill Clinton citing China as a reason for the tests, and later Defence Minister George Fernandes declaring China as India’s “Enemy Number One” hadn’t helped matters.

As the high leadership of the two nations went into huddled consultations, the journalists—all wearing huge passes declaring them to be part of the President of India’s entourage—were taken sightseeing around Beijing in a bus, flanked by police outriders with flashing lights.

After a mandatory trip to the spectacular Great Wall and other touristy places, we arrived at the massive Wangfujing Department Store, or Mall.

The smartly attired PLA guard at the entrance energetically saluted each journalist as we stepped into the mall. But his bewildered expression prompted a young lady from the Chinese Foreign Ministry, who was acting as one of our tour guides, to go have a quick chat with him. She returned giggling.

What happened, I asked. “Oh, nothing important,” she grinned. “He just wanted to know: How many presidents does India have?”

The disconnect was certainly not one-sided. During our flight to Beijing, a gentleman representing a popular Lucknow-based Hindi newspaper painted a rather vivid picture of what he was expecting. Among other things, this included elderly people in conical hats and Fu Manchu moustaches, surreptitious murmurs and Kung Fu gang wars in dark alleyways, and skinny people ferrying corpulent fat cats on their hand rickshaws through crowded streets.

If he was surprised by the city’s chrome-and-glass high rises, the broad smooth roads with fancy cars, and smartly dressed young men and women flaunting the latest fashions as they rushed silently to and from work, he hid it well.

In fact, ostentatiously pulling out a wad of hundred dollar bills, he led the charge into the mall, where among a mountain of other things, he haggled and bought a dozen “second” Rolex watches. “Guarantee for one year,” assured the store manager without batting an eyelid.

Given the language gap, haggling involved the buyer identifying the item he wanted, the store keeper keying in a figure into a large calculator, and the customer in turn keying in what he or she was willing to pay. This back-and-forth would continue amidst much excited chatter and protestations, until either one side got tired and gave up, or a mutually agreeable figure was reached.

The more intellectual part of the day involved a candid interaction with senior India watchers, diplomats and delegates from various Chinese think tanks and academic institutions.

Pointing to this gap in understanding between two ancient civilisations which grew up next door to each other, a professor remarked that while the mighty Himalayas did form a massive barrier between the two nations, there was also a distinct lack of interest, more so from the Indian side, about each other.

To justify his claim, he noted that while there was just one Indian journalist from PTI covering the entire length and breadth of China, there were at least a dozen Chinese journalists stationed in India.

“All of them spies, no doubt,” muttered a young man next to me in Hindi.

‘”Even if so, that only goes to prove my point, doesn’t it?” responded the professor in chaste Hindi, without skipping a beat. We were later to learn that all of them were fluent in Sanskrit and at least one other Indian language.

Most of them raised the Tibet issue (Ogyen Trinley Dorje, a claimant to the title of 17th Karmapa, head of the Karma Kagyu school, one of the four main schools of Tibetan Buddhism, had escaped from Tibet and been granted asylum in India earlier in 2000), describing it as far more serious than the “border skirmish” of 1962 or the nuclear issue.

Many repeated the enduring Chinese position: “The Himalayas have ensured that no battle can be fought between the two great neighbours. Why not put such things on the backburner and concentrate on areas where we can cooperate?” asked one.

“Our common interests exceed our concerns,” agreed a former ambassador to India.

As for Indian concerns about a China-Pakistan nexus, they asserted that while “Pakistan is a good friend, India is a friend. We hope that in time, India too will become a good friend.”

At the official talks between the two presidents, President Jiang Zemin had responded to his Indian counterpart’s request for a timebound framework for détente by noting that issues like the border dispute were complicated, and could not be rushed. Instead, “from a strategic height, the two countries must work for constructive cooperation in the 21st century”.

Wednesday, and we were off to Dalian, a bustling port on the north-eastern coast, about an hour and a half away aboard A-I 1.

Bo Xilai, the flamboyant mayor of the city which is also famous for its football club, was a tough act to follow.

Credited with singlehandedly turning the city from a drab port into a “Hong Kong of the north,” he met the Indian journalists in his hi-tech office overlooking the massive main square. Said to be ruthlessly ambitious, Bo took almost childlike pleasure in showing off to us how he could control colourful fountains and piped music across the square with just a click of his fingers.

Bo’s spectacular banquet for the visiting President—complete with fire eating acrobats, magicians, and whirling masked dancers—seemed aimed at outdoing the one in Beijing. This time, there wasn’t even a solitary vegetarian item on the 12-course menu.

The next day, the journalists were taken sightseeing, which included a ride aboard a PLA speedboat across the Dalian waterfront.

President Narayanan, meanwhile, had a visitor. Ms Guo Qinglan, the 85-year-old widow of Dwarkanath Shantaram Kotnis, arrived at the President’s hotel for a brief meeting, where she described the President “as a friend of China”.

Part of a medical delegation sent by the Indian National Congress in 1938 to offer medical treatment to Chinese wounded fighting the Japanese invasion, Kotnis stayed on and became a battlefield doctor, working tirelessly to save Chinese lives. Revered as a hero in China today, he married Guo in 1941, had a son in 1942 and passed away three months later.

(After a meteoric rise up the party ladder, becoming one the country’s youngest commerce ministers ever and a member of the all-powerful politburo, Bo’s downfall was equally swift. He was implicated in the murder of a British businessman in 2011, slapped with major corruption charges and expelled from all party posts. On 22 September, 2013, after a protracted trial, the court found him guilty on all counts, including accepting bribes and abuses of power and sentenced him to life imprisonment.)

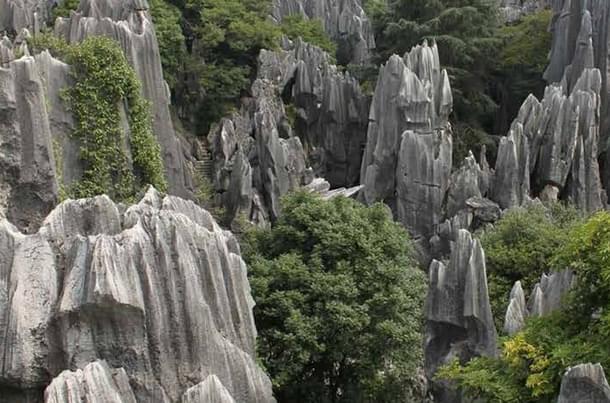

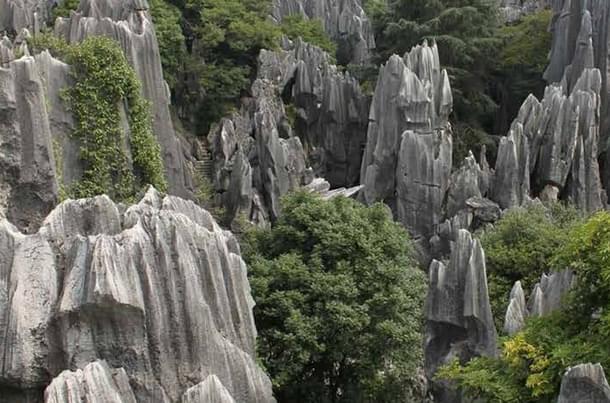

The last leg of the trip was to Kunming, the capital of Yunnan province, a four-hour flight southeast from Dalian, and about two hours away from Calcutta. Known as the Spring City, Kunming is famous for its stunning Stone Forest, described since the Ming Dynasty as the “First Wonder of the World”. It also has about 25 minorities, who are showcased in a “Village of Minorities.” These mini-villages which depict the ancient life and culture of various minorities, also happen to be highly commercial enterprises, full of ethnic restaurants and souvenir shops.

President Narayanan, who caused a minor flutter at the airport when he complained of unease and had to be lowered from the plane on a lift used to transfer food, recovered enough to visit the Kunming Academy of Sciences, and discuss cooperation between North East India and South West China.

He also found enough energy to join a traditional dance at one of the Minority Villages.

A day later, we were on our way back to New Delhi.

Fifteen years later, President Narayanan is no more. Mrs Kotnis passed away in Dalian in 2012, aged 96. Bo Xilai is in prison. Today, foreign minister Sushma Swaraj, if she had accompanied Prime Minister Narendra Modi to China, would have been welcomed with a totally vegetarian dinner.

Yet, despite the apparently growing bonhomie and Prime Minister Modi’s high-profile visit, the issues raised then—Tibet, the border and Pakistan—remain unresolved.

On both sides, the bewilderment lingers.

Ramananda Sengupta moved to the corporate world after 25 years in print and online journalism. He is an editorial consultant with Indian Defence Review, and teaches defence journalism to graduate students in his spare time.