Magazine

The Stories They Tell

Sandipan Deb

Jun 23, 2018, 03:06 PM | Updated 03:06 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

“YOU SHOULD treat the trivial things in life seriously and the serious things in life with a sincere and studied triviality.” So said Oscar Wilde, and as far as Bollywood goes, Diptakirti Chaudhuri is the uncrowned king of trivia. The man seems to have watched every Hindi film ever made, and remembered every scene and every walk-on part. And he has the two attributes that separate the men from the boys in the trivia universe. One, he can impeccably collate and correlate the facts and make lists based on the most obscure criteria. Two, he delights in trivia for trivia’s sake, and does not take himself seriously. He wishes merely to share the joy he feels when the lights go off.

Chaudhuri’s Bollybook was an astounding compendium of lists, ranging from “Heartbreak Hotel: 13 unlucky star children” and “Reboot: 8 decades of reincarnation” to “An offer you can’t refuse: 6 remakes of The Godfather or parts thereof” and “The truth about cats and dogs: 10 filmi pets”. Complete fun is assured for anyone who has misspent his youth (or middle age too, for that matter) queuing up for tickets at cinema halls, or belching over popcorn in multiplexes, or bugging their eyes out on YouTube, much to the chagrin of their near and dear ones.

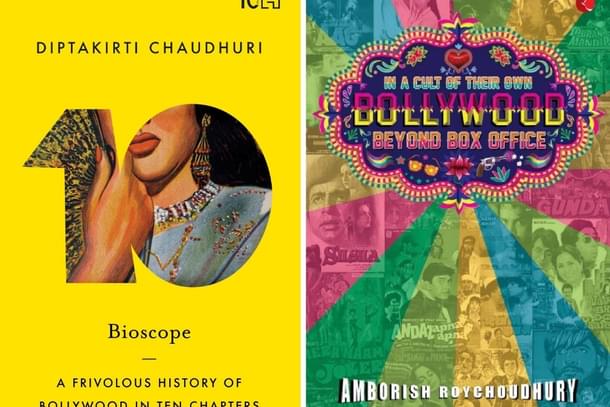

Bioscope: A Frivolous History of Bollywood in 10 Chapters sounds more ambitious, but is actually a much slimmer volume and aimed at, well, a saner and less febrile audience. It starts with box office collections, and goes on to talk about the most beloved lead pairs, the most successful teams of lyricists and music composers, about how Bollywood has influenced fashion, and so on. All chapters except the last one — how the history of independent India has been depicted by Bollywood — end with a list, where whimsy gets a bit of its rightful place. For instance, the list at the end of the chapter on hit pairs includes Ajit and Bindu — “the villain-moll pair who reached cult status for their Boss-Mona routine”. But why doesn’t this include Amitabh Bachchan and Shashi Kapoor, who possibly had more hit films than the Amitabh-Rekha duo? After all, if memory serves me correct, Bachchan, once, when asked who his favourite leading lady was, jokingly named Shashi Kapoor.

But these are minor quibbles. Bioscope, though it modestly calls itself “a frivolous history”, brims with information and anecdotes that are both interesting and valuable. We come to know that the music composer Laxmikant, after a fruitless brainstorming session with lyricist Anand Bakshi, got up to leave, saying: “Achchha, to hum chalte hain.” And Bakshi asked: “Phir kab miloge?” Lightning struck, and these became the starting lines of one of the most popular songs of the 1970s.

We learn how the final script of Gangs of Wasseypur was knocked off by Anurag Kashyap in four or five days of unbounded creative energy, when hanging around in Madrid, while his then-partner Kalki Koechlin was shooting for Zindagi Na Milegi Dobara. This was after two years of research by multiple people, voluminous material collected, and many treatments (Kashyap has made another film in between). And this script would end up as a two-part film, at a combined length of more than five hours.

In his book, Chaudhuri has looked at some of the aspects we immediately associate with Bollywood — the money, the music, the stories, the villains — and provides facts and figures, and glimpses into all the interesting stuff that we never saw on screen. It is a work of serious film history, written for the lay viewer, shorn of all filmcrit jargon, and never losing sight of the fact that all the films he talks about were made to entertain, all the men and women he writes about were dedicated to that cause, and the writer himself is not a sterile academic but a fan. Chaudhuri’s history is filled with information, but it is also opinionated, and he often wears his admiration on his sleeve. Bioscope is an insightful history, and yet an individual’s version and an emotional one. This is why it is so engaging and therein lies its value.

And it is purely because Chaudhuri is such a master of trivia that one must point out two (obviously inadvertent) factual errors. The song Pehla Nasha (page 87) is from Jo Jeeta Wohi Sikandar and not Qayamat Se Qayamat Tak. And Sanjay Gandhi (page 201) was not Indira Gandhi’s elder son.

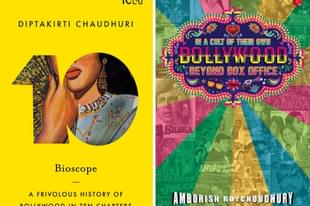

Amborish Roychoudhury’s In A Cult Of Their Own: Bollywood Beyond Box Office is history at its margins — the story of 20 “cult” Hindi films plus two chapters on the films of Joginder and the Ramsay brothers. What makes a cult film? No one really knows. Roychoudhury established his criteria for choosing his films right at the outset: “films that either flopped at release or weren’t released at all; are insufferably trashy but entertaining nevertheless; or were successful but not considered ‘mainstream’” — however, these films gained a cult following over the years and are often discussed, analysed online and have become a pop culture phenomenon.

Here, of course, I would argue that I don’t know how a Shahenshah or a Silsila fits into these categories, but then, one, I have no idea which films are discussed the most online, and two, as Roychoudhury himself says, “disagreements and debates are kind of what one hopes to instigate through this book”. So, for the purpose of this review, one will go with Roychoudhury’s list. And, anyway, I hadn’t even heard of this phenomenal film called Gunda before I read about it here.

Gunda, starring the one and only Mithun Chakrabarty (or “Prabhujee”), as far as one can make out, is a jaw-droppingly bad film — it is so utterly atrocious that it is a marvel. So much of a marvel that some students of IIT Kharagpur with a sense of humour started an online movement to get it recognised as a classic. And when IITians set their minds steadfastly to something, they usually succeed. For a time, Gunda was rated above The Godfather on imdb.com. Apparently, even now, it is rated higher than films like Cape Fear, Philadelphia and Gangs of New York. Obviously, Gunda defines “cult” in its most epic scale.

As for many of the other films Roychoudhury writes about, I found myself remembering them fondly. In fact, the evening of the day I finished reading the book, my wife and I watched Chashme Buddoor (the original 1981 one, not the recent remake that I have no intention of ever watching) on a video streaming service, after maybe three decades, and it was a lovely experience. I recalled bunking school to watch Surakksha, featuring the man who would later come to be known as Prabhujee (but also a man who has won three National Acting Awards), and wondering how he could wear trousers so tight without getting hernia.

I remembered coming back home in Calcutta, after watching Agneepath in a Saturday evening show, the week of its release, and receiving a telegram (yes, there were telegrams in those days) from a friend in Bombay, which tersely warned: “DONT WATCH AGONYPATH.” I disagreed with his opinion about the film. I was not sure whether I had liked the film or not, but I knew that I had watched something that was very different from the standard Amitabh fare, and I completely admired Amitabh for taking that huge risk of changing his voice to that nasty rasp that would always define the thug Vijay Dinanath Chauhan for the cultists. When the film was re-released two weeks later with Amitabh’s usual baritone, I thought it was quite unforgivable.

I remember watching Manoj Kumar’s Clerk on the hotel movie channel (these were the days before satellite TV film channels) in a Bhuvaneshwar hotel, with growing disbelief — how demented could this hypocritical pious socialistic patriotism get? And how could anyone expect the Hindi film audience to accept Shashi Kapoor as a totally evil man and Prem Chopra as the best man on earth? Had everyone lost their minds, or had I? I watched the whole film. The term, I believe, is “morbid fascination”.

I was paid by The Indian Express to go watch RGV Ki Aag and write about it. My review was angry enough to elicit a congratulatory call from Salim Khan, one of the two men who wrote Sholay, of which Aag was a remake. About Anurag Kashyap’s No Smoking, the less said the better. Perhaps, some cult films are born of pure delusional hubris.

Roychoudhury’s book is delightful. It needed to be written. For, for every 20 films (an arbitrary number) that will figure as the big hits or “significant” films, whenever histories are written, there is one out there that lives a life of its own and its life gets better by the day, fed by fans who have nothing to gain. Of course, this includes the outrageous as well as the brilliant, and the hosannas often have equal decibel levels as the LOL hoots, but that is something no one has any control over, nor perhaps should.

But some cult films are also ushered up the stairs to become classics. At least two of the films Roychoudhury writes about have reached there — Kaagaz Ke Phool and Jaane Bhi Do Yaaro; they are no longer mere “cult”. Hitchcock’s Vertigo did not do well either commercially or critically when it was released, lived for decades as a cult film, but today appears routinely on critics’ “50 greatest films ever” lists. As do 2001: A Space Odyssey and Apocalypse Now.

But Roychoudhury does well to select both films that are destined to remain cult movies, and those that may someday be recognised for their true worth. This is a good book. I am a film fan, and I finished it in one sitting.

Sandipan is the Editorial Director of Swarajya.