Magazine

‘Yesterday’s Films For Tomorrow’: A Great Tribute To India’s “Celluloid Man” P K Nair

Gautam Chintamani

Aug 03, 2017, 06:52 PM | Updated 06:52 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

The late P K Nair’s name is synonymous with film archiving in India, but to think of him as merely an archivist who was the head of the National Film Archive of India (NFAI) from the mid-1960s to 1991 would be a gross injustice. Called the “Celluloid Man”, Paramesh Krishnan Nair not only championed the cause of saving films as an art form but also dedicated an entire lifetime to preserving them as important visual documents of our times. Film Heritage Foundation’s Yesterday’s Films for Tomorrow is the first time that Nair’s writings on cinema have been brought together in one volume.

Reading about cinema and what it could mean by a man who has been described by the Polish filmmaker Krzysztof Zanussi as “a symbol of the memory of cinema” is nothing less than a transformative experience. Almost like watching a great film, reading about it too can in some way have the same magical experience, and to say that Nair’s writing has that capacity would be stating the obvious. Known to have watched a film a day since the early 1940s, Nair took exhaustive notes while watching films and as Rajesh Devraj, the editor of this volume, mentions in his introduction, Nair’s exhaustive note-taking had a pedagogical purpose: his shot-by-shot summaries would have been useful to scholars at a time when access to the original films was more difficult.

Yesterday’s Films for Tomorrow is divided into five segments – the Moviegoer, the Archivist, the Film Historian, the Film Critic and the Columnist – and gives a deep insight into one of the finest minds to encounter cinema. Nair, as Devraj’s insightful introduction points out, was not a writer by profession, and his writing harks back to largely “the same incidents and seminal moments in film history”. But, if one were to ponder today if imbibing Nair’s observations in this day and age has any relevance, then the answer, intriguingly enough, comes from one of his essays itself. In ‘What Price Entertainment’ (1976), Nair observes: “Unfortunately, most of our films, in the name of providing popular entertainment, are transporting our audiences to a dream world where all their social, sexual and economic frustrations find an easy outlet.” It was almost four decades ago that Nair understood that in order to break the cycle where like a “habitual drunkard who ends up a chronic alcoholic”, cinegoers, to escape the harsh realities of life, would go back to the never-never land of cinema and there needed to be a “virtuous” circle that spoke about the “positive forces operating in the field”.

Nair knew that archiving cinema in India, where almost 70 per cent of the films made before 1955 were lost, would provide a “constant exposure to genuine works of cinema” and also serve as a reminder to the future generations as to why this was necessary. The journey of Nair’s life is also the journey of film archiving in India where the NFAI, which began with less than 100 titles, thanks to Nair’s pioneering efforts, had almost 12,000 by the time he retired as director in 1991. In fact, lyricist and filmmaker Gulzar believes that Nair’s name in our history of cinema should be immortalised like Dadasaheb Phalke’s, as Phalke might have been the founder but it was Nair who “gave him a place in history”. Nair had also set up the Archive’s influential film appreciation classes and built a library that sent prints of the classics to film clubs and societies across India.

The manner in which Nair’s writing deconstructs cinema or the act of creation is not limited to understanding the director. Like he himself describes, “approaching the act of creation from the other side, as it were, can become an imaginative endeavour in itself”. Most of the essays in Yesterday’s Films for Tomorrow also reveal the basis of many ideas on the subject of cinema that remain widespread even today. One of the first jobs that Nair ever had gave him the opportunity to observe Mehboob Khan as an assistant during the making of Mother India (1957) and the way Nair deciphers the flamboyant filmmaker in ‘Mehboob As I Knew Him’ not only sums up the filmmaker’s process but also decodes him for today’s generations.

Nair mentions that watching Andaz in 1949 for the first time made him aware of a “certain slickness and technical polish in an Indian film”. He talks about how a small party scene – the lights go out and Nargis walks up to Dilip Kumar and tells him that there is no place for him in her life and that he should leave her in peace, but when the lights come on, she realises her folly as the person she spoke to in the dark was not Kumar but her husband, Raj Kapoor – shows the audience the filmmaker’s deep understanding of human beings, their hopes, aspirations, conflicts and frustrations.

Reading about Nair, one often wondered what could have been the criteria for preserving films in a country such as India where the output is so large. In the essay that also gives the collection its title, Nair lists out the reasons and even sums it up wonderfully: “The preservation of national cinema is the primary concern of any film archive: If we are not going to preserve our films, nobody else is going to do it for us.” One of the best pieces in the collection is ‘The Evolution of Film in India, Seen Through Posters’, which, besides being a visual treat, is also a chronicle of the first relationship that the viewer has with a film, right from the earliest days where display posters were the norm to the 1970s and the 1980s.

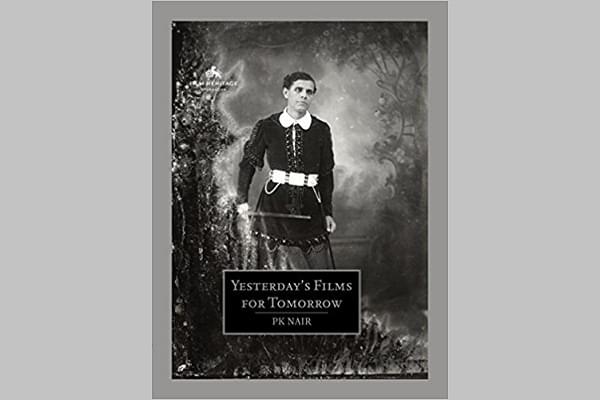

In a life dedicated to preserving cinema, there would surely have been some unfulfilled dreams, and Nair talks about 10 of the ones that he could not save in ‘The Ten I Miss Most’. The list includes Mazdoor (1934), a film written by Munshi Premchand that was shot mostly on location in a textile mill in then Bombay, Khoon Ka Khoon (or Hamlet, 1935), Sohrab Modi’s debut as an actor and director whose image also adorns the cover and, of course, Alam Ara (1931), India’s first talkie and Sairandhri (1933), India’s first colour film. Nair was often asked why he never ventured into filmmaking, and in the piece called ‘Training Future Filmmakers: New Approaches’, he mentions that he “would rather make filmmakers than films”. Perhaps this is the single line that best summarises P K Nair, the custodian of cinema.

Yesterday’s Films for Tomorrow is not just a “must read” or a “must have” but it is a must pass-on, for this would be the greatest tribute to the man who has done the most for the legacy of Indian cinema.

Gautam Chintamani is the author of ‘Dark Star: The Loneliness of Being Rajesh Khanna’ (2014) and ‘Qayamat Se Qayamat Tak- The Film That Revived Hindi Cinema’ (2016)