Obit

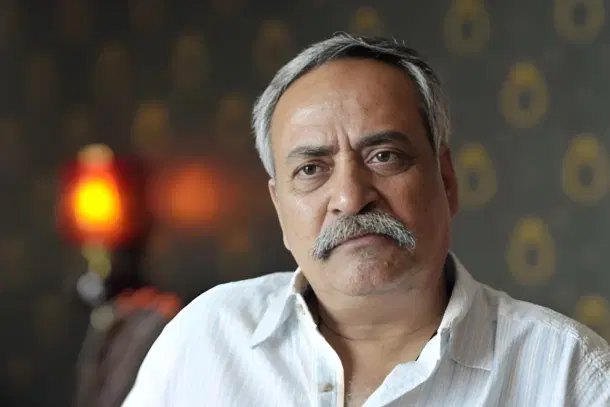

Kuch Khas Tha: The Life And Legacy Of Piyush Pandey

K Balakumar

Oct 24, 2025, 02:54 PM | Updated 02:54 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Back in the mid-1990s, when I had just stumbled into journalism after a short-lived flirtation with advertising, I was assigned to interview ad men in Madras for a fortnightly column in the newspaper I worked for at the time. Brimming with textbook enthusiasm and a little self-importance, I would often lob questions about famous western ads. Typically, the Coca-Colas, the Nikes, the Volkswagen one-liners that I thought represented the gospel of creativity.

But on at least two occasions, two very different ad veterans stopped me in my tracks. They insisted that it was silly to look west when Indian ads, with their colloquial language and homegrown ideas, were already doing a far better job. Both of them invoked the same name as the architect of this new and vibrant ethos, Piyush Pandey.

Then, I did not know he was an emerging legend. Now, we know he is an Indian ad pioneer.

Piyush Pandey, who passed away yesterday, was one whose words, phrases, and sheer, unapologetic Indianness shaped how millions laughed, celebrated, and even voted. Pandey was not just the Ogilvy India doyen. He was the great bard of modern India’s consumer culture, a pioneer who tore down the glass walls of anglicised elitism that once defined the profession and planted the earthy, vibrant flag of desi creativity firmly in its soil. He was the romantic of advertising, the man who believed that even in the age of data and algorithms, creativity was ultimately an act of humanity.

From the pitch to the people

Piyush Pandey's journey to becoming the voice of a billion people began, strangely enough, with the sound of leather hitting willow. Born into a large family of nine siblings, including the acclaimed director Prasoon Pandey and the celebrated singer-actor Ila Arun, Piyush (sometimes spelled Pijush) carried a deep creative streak nurtured in the halls of St Stephen’s College, Delhi, where he completed a master’s in history alongside the likes of cricketer Arun Lal.

Before advertising, there was cricket in his life. For a bit in the late 1970s, he played Ranji cricket for Rajasthan as a wicket-keeper and competed against the likes of Kapil Dev. It was cricket at a decent level and, as it happened, it was his early field research for his later work.

As he detailed in his memoir Pandeymonium, the cricket trail, especially the arduous, crowded train journeys, exposed him to the beating pulse of real India. That experience of meeting people from all classes, hearing their dialects, and observing their daily lives became the reservoir from which many successful ad campaigns would flow later.

These outings also codified one of Piyush’s core beliefs, a thought he distilled in his book. "Real research is where you pack your bags, get out of your comfort zone and stop by the roadside."

Fusing Desi with the 'Big Idea'

When Piyush Pandey entered the advertising industry, it was still mimicking Madison Avenue. Ads were English-heavy, featuring models who felt far removed from the average Indian. Or the ads were too provincial. Piyush changed the game by changing the language. He proved that ads in Indian dialects were not a compromise but the very source of power and connection.

He took David Ogilvy's global concept of the Big Idea and fused it with Indian authenticity, creating a new advertising grammar.

His campaigns became cultural milestones, creating phrases that transcended the product to become part of the national vocabulary. For instance, Cadbury Dairy Milk’s Kuch Khaas Hai (There is something special in all of us) campaign shattered the cliché that chocolate was only for children. The sight of a woman in a cricket stadium running onto the field and dancing unabashedly as the batsman, her boyfriend, scored a six to reach his century redefined celebration and indulgence for adults. It was a moment of pure, innocent joy, a desi affirmation of life’s small, uninhibited pleasures.

Another celebrated campaign was for Fevicol, as he transformed everyday adhesive into a beloved cultural icon through situational, rural-centric comedy. Whether it was the crowded bus that would not break because of Yeh Fevicol ka jod hai, tutega nahin or the hilariously stubborn FeviKwik fisherman, the humour was instantly relatable and shared across class divides. Incidentally, his Fevicol ad with the line Dum Laga Ke Haisha featured the unknown newcomer, Piyush’s friend Raju Hirani.

The Asian Paints Har Ghar Kuch Kehta Hai (Every home tells a story) ads elevated the mundane act of painting into an emotional storytelling exercise, capturing the essence of the Indian home as a repository of memories, tradition, and family life.

In that sense, Piyush was the great connector, understanding the power of simplicity over complexity. He once famously said, "I don’t write ads, I tell stories." His stories were simple, drawn from the ordinary, which is what made them extraordinary. He emphasised the need for creative generosity, noting in his book, "the more insecure you are about your idea, the less you will share it and the less the possibility for a good idea to become great."

Musical moment and political pulse

Piyush did not just sell products. He, in a sense, sold the spirit of India back to itself, reminding Indians that there is indeed something special in all of us.

Piyush’s impact stretched far beyond the commercial ledger. In 1988, he wrote the lyrics for the national integration song Mile Sur Mera Tumhara. That musical lilt, the natural ad zing he possessed, was distilled into a piece of art that remains a gentle reminder of the nation's diverse, harmonious soul. The story of its creation, where the simplicity he sought was so elusive that his eighteenth draft was finally approved, underscores his relentless pursuit of the perfect connection. The song's enduring resonance proves his ability to weave lines that speak to the average Indian's heart.

The lines between art and politics also blurred in Piyush’s world as his words travelled where people did. In 2014, when the BJP sought to rebrand itself for a generation tired of political sameness, it turned to him. Ab ki baar, Modi Sarkar was Pandey’s brainchild, a simple phrase that echoed across loudspeakers, WhatsApp messages, and chai stalls. The line Achche din aane wale hain was short and persuasive in its cadence. It did not sound like propaganda. It sounded like conviction.

It was a textbook example of transforming a political campaign into a brand promise. His versatility even took him to the silver screen, where he appeared in the film Madras Café in the role of a Cabinet Secretary, a quiet cameo that subtly underscored the vast canvas of his creativity.

The legacy that will live long

Piyush's career was a constant upward climb that placed Indian creativity on the global map. Under his stewardship, Ogilvy India became a creative powerhouse, nurturing generations of talent and being consistently ranked the number one agency for years.

His achievements were not mere listings on a resume. Piyush was the first advertising professional to receive the Padma Shri in 2016, an honour that legitimised the creative profession in the eyes of the establishment. In 2018, he and his brother, Prasoon Pandey, became the first Asians to be feted with the Lion of St. Mark at the Cannes Lions International Festival of Creativity, the industry's highest lifetime achievement award, recognising their role in bringing Indian stories to the world stage.

His relentless commitment to social good manifested most powerfully in the Pulse Polio campaign with Amitabh Bachchan, which used the simple, humanising line Do Boond Zindagi Ke (Two Drops of Life) to drive massive social change that led to the eradication of polio from India.

An unbreakable jod

In every sense, Piyush was a generational pioneer because he did what his contemporaries, often looking outward, could not. He rooted himself in the land. He taught the industry that the greatest ideas are not clever imports but simple truths drawn from the life of the common man.

Though his famous lines may have been Hindi, he intrinsically understood that emotion can be a bigger, more universal mother tongue. Hence his ads worked without the need for translation. Chal meri Luna did not require a Malayalam or Tamil version to reach the people.

It can be no exaggeration to say that every ad today that comfortably mixes Hindi and English, that finds pride in rural idiom, and that celebrates the ordinary Indian rather than exoticising them, carries a drop of Piyush Pandey’s ink.

As the industry mourns, every Indian who smiles at the memory of the dancing girl in a cricket field, who feels the unbreakable bond of a Fevicol joke, or who remembers the reassuring call of the Hutch Pug following a little boy in a yellow raincoat, is mourning with them.

Piyush Pandey’s passing, to use a cliché he detested, marks the end of an era, but his influence is immortal. The language he spoke, that of the street, of the village, and of the home, will continue to echo in the heart of every storyteller who dares to speak shuddh desi truth.

Go well, Piyushji. The jod you created will never break.