Politics

1991-2017: The Epic Saga Of Elections In Uttar Pradesh

Atul Chandra

Feb 04, 2017, 02:52 PM | Updated 02:52 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Uttar Pradesh has seen shades of red and green, saffron, and blue dominate the state’s political spectrum over the last 25 years as India’s ‘grand old party’, the Indian National Congress, lost its space to regional satraps and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

Beginning in 1991

As communal and caste cleavages widened, the high points of this phase, since 1991, were the rise of the Bharatiya Janata Party, and that of the Dalits and Backward Classes in the state’s politics. While December 6, 1992 was a watershed moment, no less significant was the emergence of Dalits and OBCs as the new political elite.

Political instability marked the period between 1991 and 2003 in Uttar Pradesh, with ten chief ministers playing musical chairs of sorts and President’s rule being imposed three times.

The period between 1985 and 1989 and 1990-92 were especially tumultuous. Vir Bahadur Singh, who had taken over as the Chief Minister in September 1985, gave in to the request of Vishwa Hindu Parishad to get the gates of Babri Masjid/Ram Janmabhoomi at Ayodhya unlocked. The move opened the floodgates to a controversy that is yet to be resolved and proved suicidal for the Congress.

The Bharatiya Janata Party and the Vishwa Hindu Parishad gradually built up a campaign for the Ram temple in Ayodhya and Vir Bahadur Singh’s decision was a shot in the arm for them at a time when the BJP had lost the 1985 elections to the Congress.

From shilanyaas to the temple

After the gates to the structure were opened, the VHP upped its ante and started clamouring for more. In the months that followed, its movement for a Ram temple began to gather steam as the outfit mobilized public opinion and sought the government’s permission to perform shilanyaas at the disputed structure.

In 1988, ND Tiwari replaced Vir Bahadur as Chief Minister and remained in office till December 1989. The year saw a desperate Rajiv Gandhi, the Prime Minister, looking for a straw to latch on to in order to retain power at the Centre. Instead of countering the VHP leaders’ plan to perform shilanyaas, Tiwari played into their hands in the hope of winning Hindu votes. The shilanyaas, described as a landmark event in the Ayodhya movement, was performed at the disputed site on November 9, 1989 with the tacit approval of his government.

By allowing the ceremony to happen the Congress government thought that it has pleased the Hindus. However, even while permitting shilanyas, its intended game plan was to stall the construction of the temple. This way, Congress strategists expected both Hindus and Muslims to be won over.

Neither of the communities, however, swallowed the bait and the move backfired.

The Congress party lost the 1989 Lok Sabha elections and VP Singh, who led the offensive against Rajiv Gandhi, became the Prime Minister of the National Front government comprising of his Jan Morcha and the Janata Dal, with the BJP and the Left parties playing a supportive role.

The shilanyaas, in the meantime, paved the way for the demolition of the Babri Masjid, and for backward class politics to take centre stage in the state with Mulayam Singh Yadav becoming the chief minister on December 5, 1989 as a leader of the Janata Dal.

The birth of BSP

Amidst these developments, a blip on the political radar, however, went unnoticed. The Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP), which was formed by Kanshi Ram in 1984 with the objective of empowering the Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, OBCs and religious minorities, bagged 12 seats.

The state’s political fortunes were closely linked with the developments at the Centre. With the VP Singh government collapsing in November 1990, Mulayam decided to join Chandrashekhar’s Janata Dal (Socialist) so as to continue in office with the backing of the Congress.

Throughout late eighties the temple protagonists kept up the pressure on successive governments in the state. The sound turned into a crescendo as the BJP saw an opportunity in the temple movement to gain political power in the country’s biggest state, which could then propel it to power at the Centre. It was a religious movement which camouflaged BJP’s political ambitions and the party was in no mood to let go of the chance.

Maulana Mulayam

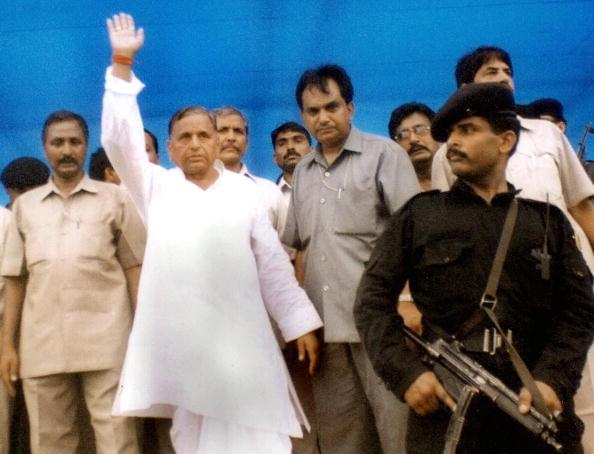

Chief Minister Mulayam Singh Yadav realized that the Congress, after its failed strategy, had left a void which he could fill by taking on the VHP. When in October 1990, thousands of kar sevaks marched towards Ayodhya, Mulayam first tried to prevent their march and later ordered police firing at them. This and others of his Muslim-centric policies won him the epithet of ‘Maulana Mulayam’ even as feelings against him ran high among a large section of the people on account on the firing on the kar sevaks.

In 1991 the Chandrashekhar government at the Centre fell after the Congress withdrew its support. As a consequence, Mulayam’s government in UP, which was also dependent on Congress for survival, had to go.

Mid-term elections to the state assembly followed and with the majority sentiment against him, Mulayam Singh was defeated as his party could win only 30 seats.

Ram lala hum aaenge, mandir wahin banaaenge

For the first time, riding the Hindu wave with slogans like Ram lala hum aaenge, mandir waheen banaaenge, the BJP came to power winning 221 of the 425 seats of the state assembly (Uttarakhand was yet to be created).

The saffron hue which UP politics had acquired by then came to dominate the developments which followed with Kalyan Singh, a Lodh leader, being appointed the chief minister on June 24, 1991.

Soon after taking over as chief minister Kalyan Singh earned the reputation of being a tough and able administrator, a reputation which his successors could not match. In fact, he himself could not repeat his mojo when he became the chief minister for a second time.

The mosque at Ayodhya being in the BJP’s cross hairs, Kalyan Singh visited Ayodhya immediately after taking oath to pay his obeisance and vowed to build a Ram temple there as promised to the electorate. Four months later, in October 1991, his government acquired land around the Babri Masjid complex.

In July 1992, the VHP and the Rashtriya Swayam Sewak Sangh (RSS) laid, what they called, the foundation of a Ram temple by constructing a platform near the Babri Masjid. The Kalyan Singh government called it a platform for performing bhajans.

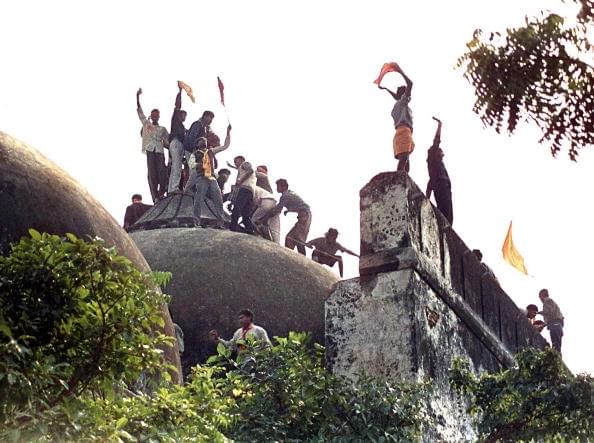

With the VHP, Bajrang Dal and the RSS bent on performing kar seva in Ayodhya on December 6, 1992, Kalyan Singh assured the Supreme Court that as chief minister he would not allow the kar sevaks to damage the structure.

As it turned out, the chief minister did not keep his word and kar sevaks brought down the Babri Masjid on the sixth day of December, 1992, leading to political and social upheavals in the state and the country.

Adding to a long list of governments which lasted for a little over one year, Kalyan Singh’s government was dismissed and UP was placed under President’s rule. In this term, Kalyan Singh was in power for one year and 165 days.

President’s rule was then lifted after 363 days and the dice was rolled for another round of elections.

The BJP was all charged up after the Ayodhya developments and was confident of returning to power on the Ram temple plank, once again raising its earlier slogan of Ram lala hum aaenge, mandir waheen banaaenge.

Mulayam creates the Samajwadi Party

For far too long Mulayam had worked as an appendage of different national parties even while retaining his individual political identity. A shrewd politician, he realized that the Congress graph was on the decline and decided to carve out a path for himself. With the objective of carrying forward the legacies of Ram Manohar Lohia and Chaudhary Charan Singh, Mulayam floated his own party on October 24, 1992, a couple of months before the demolition of the disputed structure.

In keeping with his socialist moorings, Mulayam named his outfit the Samajwadi Party, or the Socialist Party.

If in 1991 the BJP was the voters’ favourite because of its emotional appeal, the 1993 polls saw Mulayam aggressively campaign against the “communal BJP” as he mobilized Other Backward Classes and the Muslims to vote for his party.

The results came as a setback for the BJP which slipped from the high of 221 seats in 1991 to 177, presumably because it had failed to deliver on its promise of Ram temple as the issue had been taken to court.

The Congress, already losing its appeal, was routed from a state which it called its own. The party could manage only 28 seats, its lowest tally in the state until then. (A mix of issues like leadership crisis, the blow dealt by Muslim and Hindu voters and bankruptcy of ideas saw Congress numbers fall further to 22 seats, in the 2007 elections).

The other important fallout of the 1993 elections was the demise of the Janata Dal (JD). From a high of 202 seats in 1989 to 92 in 1991, the JD had slipped to 27 seats, one less than the Congress.

Mulayam became the flavour of the season for having stopped the BJP juggernaut.

Even though the BJP remained the largest single party, Mulayam’s Samajwadi Party was placed second with 109 seats. Meanwhile, led by Mayawati, the BSP too significantly improved upon its tally with 67 seats and the Congress numbers declined from 46 to 28.

The results changed the state’s political template from communal to caste politics and in the new paradigm Mayawati and Mulayam became two regional satraps to be reckoned with.

The wily Mulayam managed to stitch up a coalition with the BSP agreeing to support him as the Chief Minister. The Congress-I, Janata Dal and the Left parties backed the coalition. As he outsmarted the BJP and cemented his position as a leader who was capable of halting the BJP’s march, Mulayam told an interviewer that there “was going to be no problem” with the BSP.

However, differences soon began to creep in. As relations between them turned acrimonious, the BSP withdrew its support cutting short the life of the Mulayam government to one year and 181 days.

Samajwadi Party workers responded to Mayawati’s decision with violence. Mayawati, who was staying in the State Guest House at Mirabai Marg, Lucknow, was attacked by SP goons led by the party’s legislators with the alleged connivance of the police. She had to lock herself inside a room when some SP workers tried allegedly tried to molest her. Cases were registered against Mulayam, his brother Shivpal and others.

After the incident, Mulayam and Mayawati became permanent enemies and the Samajwadi Party came to be branded as a party of goondas.

After almost nine hours of hooliganism, Mayawati was eventually rescued by BJP leaders, mainly LK Advani, who agreed to extend outside support for the BSP supremo to form a government to checkmate Mulayam.

1995: Mayawati is Chief Minister

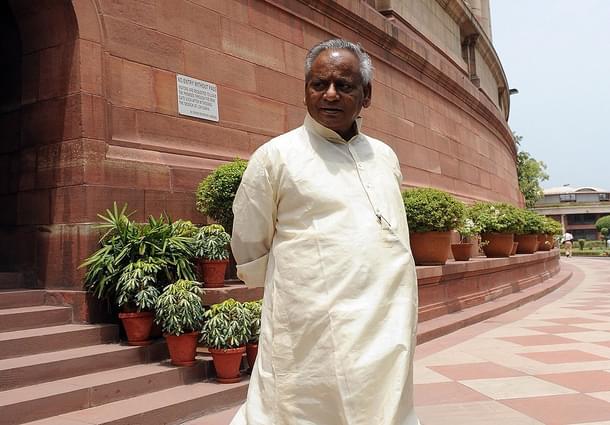

On June 3, 1995, Mayawati became the first Dalit, a woman at that, to be appointed Chief Minister of the state.

The marriage between BJP and BSP however did not last. After she was in power for a mere 137 days, the BJP withdrew its support. Kanshiram was quoted as saying that he was “not surprised that votaries of Brahminism have betrayed us”. The House was dissolved and for the second time after December 6, 1992 the state was placed under Presidents rule, this time for a longer period of one year and 154 days.

Elections were announced in March 1997 and for the second time after 1993, the voters gave a splintered verdict. The BJP retained its status as the largest single party, even though its tally declined marginally to 174. The SP gained one seat to finish with 110 and the Congress too gained a little and moved up to 33 seats. The JD with seven seats was decimated.

The BSP had fought the 1996 elections in alliance with the Congress but the formula did not work as the two together won a 100 seats. Although driven by caste politics it had become an important political player in the state, the BSP’s numbers remained static at 67. Even its slogan of “tilak, tarazu aur talwar, inko maaro joote chaar”, targeting the upper castes did not work.

Consequently, she and her mentor Kanshiram decided to change their strategy and began talking of social engineering to move out of the Dalits-only syndrome as they worked out a plan to form a minority government in their relentless pursuit for power.

Kanshiram, who had forged an electoral alliance with the Congress with Narasimha Rao’s blessings, now approached Atal Bihari Vajpayee and LK Advani for an arrangement under which Mayawati was to be chief minister for six months after which she was to relinquish office for Kalyan Singh. The BJP leadership being amenable to the idea, Mayawati became the chief minister of UP for a second time.

In time, when Kalyan Singh’s turn came to don the CM’s mantle, the BSP demanded the Speaker’s post. As per the agreement between the two parties, the Speaker’s post to remain with the BJP as it was the single largest party in the House. As BSP’s tantrums increased, the idea of chief minister by rotation had to be junked.

Kalyan Singh returns

With Mayawati pulling the rug in October 1997, Kalyan Singh, on his part, engineered a split in the Congress. Naresh Agarwal led 21 other disgruntled Congress MLAs to form the Loktantrik Congress to bail out Kalyan. On September 21, 1997, Kalyan Singh became the CM for a second time.

His stint was marked by the dramatic development of Jagdambika Pal of being sworn in as chief minister for all of three days after the LCP withdrew its support to Kalyan Singh’s government in early 1998. Pal had indeed set a dubious record for himself and the state.

Kalyan Singh, who had by now acquired a larger-than-life image after his role in the Ayodhya issue, however failed to deliver in the Lok Sabha elections in 1999 which were held during his chief ministership. The party’s strength had plummeted to 29 from 57 in 1998 and Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee was bent on removing him.

Kalyan Singh exits

Even as Kalyan criticized the party for “forgetting about the Ayodhya temple”, the septuagenarian Ram Prakash Gupta was named to replace him. Gupta was appointed to quell rebellion in the state unit but ended up alienating party workers with his ineptitude. After he was in office for 351 days, Gupta was removed and Rajnath Singh, who was then a Union minister, became the chief minister.

His tenure ended with that of the thirteenth assembly and the state went to polls once again in 2002.

The political roller coaster saw a people’s mandate which was too fractured for any party to form a government.

2002: A mandate heavily fractured

That the BJP was fast losing ground in the state was evident from the seats it won—88. The BSP emerged stronger with 98 seats, 31 more than the 67 it won in the previous election. Samajwadi Party with 147 legislators was the largest single party but was too short of the required numbers. The Congress was down from 33 to 25.

With no party in a position to form government, governor Vishnu Kant Shastri recommended Central rule to prevent “horse trading”. The House was kept in suspended animation.

The thirteenth Vidhan Sabha of Uttar Pradesh was unique in that it had four chief ministers (leaving out Pal) between March 1997 and October 2000. It began with Mayawati who was followed by Kalyan Singh, Ram Prakash Gupta and then Rajnath Singh. For a party with difference this was unprecedented. Only Congress had shuffled its chief ministers like the BJP had done now.

When President’s rule ended after 56 days, the BJP once again agreed to give outside support to a government headed by Mayawati.

In a rerun of the previous such experiment, the two strange bedfellows soon parted ways and Mayawati’s third term as chief minister ended on August 29, 2003.

A master of political intrigue, Mulayam was only waiting for a situation like this to emerge. He engineered a defection of 37 BSP legislators and five Independents to his side. The Congress and the RLD agreed to throw their weight behind Mulayam too.

With the defectors telling the Governor that they did not want another round of elections the SP president took over as the chief minister for the third time on August 29, 2003. A long legal battle ensued to decide whether the defections fell under the purview of anti-defection law.

By the time the Supreme Court disqualified the defectors, the term of the Vidhan Sabha was over and it was time for elections once more in 2007.

The notoriety of ‘Mulayam raj’ and the grand victory of Mayawati

By end of 2006 the SP government had acquired enough infamy on account of poor governance, abysmal law and order situation and slow pace of development. In the event, the party could win only 97 seats when polls were held in 2007.

What was remarkable about these elections was that the voter had realized the problems associated with coalition governments and gave a majority verdict in favour of Mayawati. She became the first chief minister after 1991 who did not have to worry about any coalition partner playing hard to please or withdrawing its support. The BSP won 206 seats, ending a long phase of political instability in the state.

The BJP found the Ayodhya card losing its sheen further as the party was reduced to 51 seats while with only 22 legislators Congress seemed to have lost the voters’ trust even more.

The BSP’s triumph was attributed to a change in its attitude towards the upper castes, or Manuvadis as Mayawati used to refer to them. Confident that her Dalit vote bank, mainly the Chamars, was securely behind her, she coined the slogan of sarvjan hitaay and embraced upper castes and Muslims, besides the OBCs, in her party fold.

As there was no threat to her government from any quarter, Mayawati began splurging on stone statues and soon her government came to be dubbed as corrupt. The National Rural Health Mission scam proved to be the proverbial last nail in the coffin. Despite efficient handling of the law and order by her government, Mayawati lost miserably in the assembly elections in 2012.

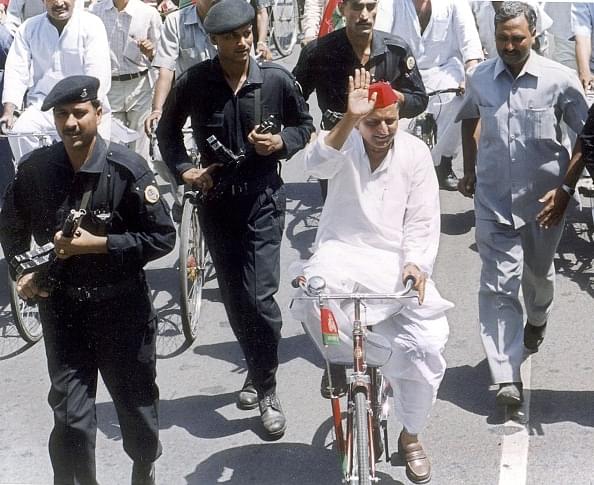

2012: Mulayam hands over to Akhilesh

The Samajwadi Party, which had acquired notoriety for its pro-criminal image, returned to power stronger with 224 seats primarily because Mulayam had allowed his son Akhilesh to lead the campaign and the voters were impressed by his youthful charm and energy. Akhilesh was free from the negative image of his father Mulayam and uncle Shivpal Yadav, a factor which trumped Mayawati.

The BJP lost ground further winning only 47 seats but the Congress numbers went up a few notches with 28.

With the 2017 election process underway and all the political parties facing rebellion from within the moot question being asked is if the voter will persist with the stability factor or give a split verdict after two stable governments. Thanks to the Election Commission, political parties cannot play on the sensitive issues of caste and community openly even as each player has tried to get its arithmetic right in those two areas.

How will the history of the 2017 elections in Uttar Pradesh read? Watch this space.

Atul Chandra is former Resident Editor, The Times of India, Lucknow. He has written extensively on politics in Uttar Pradesh.