Politics

A Dalit Family Is Humiliated With Casteist Slurs At Temple Gate. A Panchayat ‘Resolves’ The Matter

Swati Goel Sharma

Jul 23, 2020, 12:24 PM | Updated 12:24 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

On the morning of 29 June, Anuj Kumar and his elder sister went to a Shiva temple in their village – Gram Gopalpur in Nurpur block of Uttar Pradesh’s Bijnor district.

It was around nine and the temple was being cleaned with water. One local, Sanjeev Sharma, was present at the premises.

Anuj told this correspondent that Sanjeev stopped the duo from entering, telling them to come later once the temple is clean and the floor dry. Anuj said he needed only two minutes, that all he had to do was offer water to the shivling and leave for work.

Sanjeev snapped at him, saying “Chamaar chamatte saale aa jaate hain puja karne, inse ghar mein puja nahi ki jaati hai (low-castes come to the temple to pray as if they can’t pray at home)”.

“Chamaar chamatte” is a caste slur and is punishable by law under the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989.

Yet, its use is not uncommon.

A Harijan family is stopped at temple gate and told - âlow-castes come here right in the morning, canât they pray at homeâ

— Swati Goel Sharma (@swati_gs) July 15, 2020

When the family objects to the filthy language, the richer, upper caste men gather a mob and beat them up

I hv covered several such cases, this is latest pic.twitter.com/NHPtjyOpS2

Anuj, 21, belongs to a Scheduled Caste. Sanjeev, as per Anuj, belongs to ‘Badhai’ (carpenter) caste and, though he is not a Brahmin by caste, he uses ‘Sharma’ as surname “as is the custom”. Sanjeev is about 38.

Filled with rage, Anuj told Sanjeev that he has no authority to order him to leave. In reply, Sanjeev held his sister’s arm and twisted it, cracking some of her bangles. Anuj somehow freed her and left. He returned with his brother a few minutes later, only to find Sanjeev accompanied by several burly men, including the village pradhan Rambahadur Sharma.

The bigger group beat up the two brothers, says Anuj. He was angry, but had to tread with caution as the pradhan was involved.

As per Anuj, the village has about 140 Harijan families against some 200 “upper-caste” families, out of which only 15-20 are Badhais. There are about 30-35 Muslim families too. The Badhais, though few in numbers, mingle with the majority population of Sainis, Chauhans and Brahmins.

The Harijans live in a separate lane; so do Muslims.

A similar incident, though not related to a temple, took place three years ago too, and the same Sanjeev was involved, says Anuj.

“We thought hard, consulted with a few neighbours, and decided that this time, we won’t tolerate it. We decided to go to the police,” says Anuj.

The experience left him disappointed. He says the police took his written complaint, but did nothing about it. “Prashasan inhi ka hai, inhi ki taraf hai (administration is theirs, it sides with them),” he says, explaining that the local police head also belongs to an upper caste.

Two days later, stones were pelted in the Harijan lane. There was firing too, says Anuj. Fortunately, no one was hurt as residents were inside their homes at that time. The matter was reported by local media.

Senior officials inclduing the sub-divisional magistrate and circle officer visited the spot the next day. Anuj says the visit meant nothing as his earlier complaint was still not taken seriously.

He says there are two temples in the village, and both are open for all residents irrespective of their castes. That, however, does not mean there is no discrimination.

“On the surface, it seems we and they are just the same, and are neighbours. But in moments of confrontations such as this, they reveal their real thinking. They spare no chance to show us our place,” says Anuj.

“Does a temple not belong to all? It does. But they will never stop a Saini or Chauhan at the gate the way they stopped me.”

Anuj says that the relations are cordial only till the time the “lower castes” don’t open their mouths. “We lower our gaze when they walk by. We don’t offer our opinion in any gathering. We remain quiet and simply nod,” he says.

Taking the temple matter to the police earned him the ire of the dominant castes. The entire Harijan lane paid the price for it, as stones landed on all their houses. Some Harijans even complained to Anuj the next day for escalating the matter.

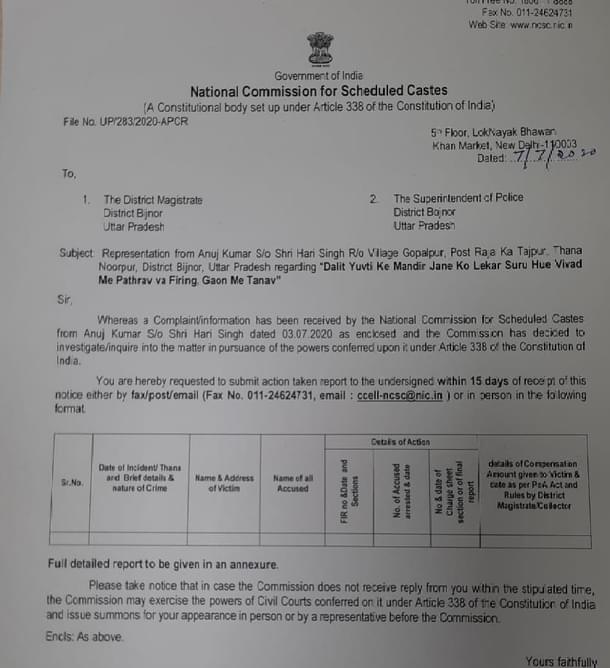

Fortunately for Anuj, Dalit organisations visited him after they learnt about the firing case in newspapers. One of the activists, Bhupendra Singh Jaatav, took the case to the National Commission for Scheduled Castes (NCSC), a Delhi-based constitutional body.

A letter, signed by Anuj, asked the commission to direct the local police to lodge a first information report (FIR) and take appropriate action.

On 7 July, the commission sent a notice to the Moradabad police chief asking him to respond to allegations made by Anuj. The commission gave 15 days to the police to send its written response.

News of NCSC’s notice to the Moradabad top cop reached the villagers and caused a stir. Four days later – on 11 July – a panchayat was organised. It saw participation of some adjoining villages too.

Anuj says the main accused, Sanjeev, apologised with folded hands to Anuj and his father Hari Singh. “All is well now,” says Anuj.

“The panchayat also decided that temple cleaning would now take place only after 11 am and not early morning.”

Bhupendra Singh told this correspondent that the matter “stands resolved”.

“Some men also got the danda treatment by the police. That was needed because they went so far as pelting stones and firing at the Harijan colony. But as of now, the matter stands resolved and none of the parties wishes to escalate it,” he said.

The complaint, thus, never turned into an FIR, he informed, adding that had it not been for NCSC’s intervention, villagers would not have organised the panchayat.

Such cases where the dominant upper-caste villagers humiliate fellow villagers belonging to Scheduled Castes at the temple gate aren’t uncommon and, usually, they end up in similar compromises.

This correspondent has covered two similar cases from Uttar Pradesh.

In the first case reported in August 2018, a wandering sadhu made a vacant room beside a ‘samadhi’ his abode. He began to have a tiff with the local boys for drinking just outside the samadhi. One day, he told the boys to leave, saying they were from a lower caste and must go elsewhere.

As the matter reached the village pradhan, he ordered the sadhu out of the village. Yet, Dalit youths in the area – mainly from student bodies – staged a protest outside the police station. Some of them, sensationally, even threatened to convert to Islam.

When this correspondent visited the village a few days later, residents said the matter “had been resolved” even before the protest. They said the protest was a mischief by student political leaders. A week after the incident, a rights organisation named Agniveer organised a community havan at the samadhi with participation of all castes.

In the second case reported in November 2019, a group of Valmiki women were stopped at the temple gate by a man from the dominant Thakur community, who told them the temple stands on land owned by his grandfather.

As this correspondent reported, this temple prohibition came a few days after some Valmiki women left a bhandara organised by a Thakur man, alleging discrimination.

A video of the spat at the temple gate was captured on mobile phones and went viral, prompting outrage on social media and action by the police.

Unlike in the previous case, the police lodged an FIR this time, and booked several men for rioting and criminal intimidation and also under the SC and ST Prevention of Atrocities Act.

However, this matter too was “resolved” with a compromise among villagers over the next few days. As this correspondent reported a month after the incident, a Dalit groom visited the same temple for a wedding ritual without any objection.

Regarding Bijnor case, Anuj’s father Hari Singh told this correspondent that he isn’t convinced that the matter has been resolved. He says the panchayat was a “dikhawa” (show). He says the upper castes throw “ainth” (attitude) at Harijans all the time.

“This Sanjeev is so arrogant that he has got ‘vidhayak’ written on his car even if he isn’t one,” he says.

Singh says that during the spat at the temple, Sanjeev and his group told Anuj – “Tere baap ka mandir hai kya (does the temple belong to your father)”.

“That’s hurtful. I admit we give only Rs 10 or Rs 20 in donations while they give as much as Rs 500. But that doesn’t make them the father of the temple either.”

Singh, however, says he has no choice but to accept the decision of the community.

When asked about it, Bhupendra Singh said that while he agrees that such compromises are only a temporary solution, the Dalit community can’t afford to devote more time on these issues.

“We have much bigger problems to deal with. Our daughters are being abducted everyday. Non-Dalits get fake SC certificates made and keep us deprived, I fight these cases day in and day out,” he said.

“The temple issues need reform from within the Hindu community. It needs intervention of various Hindu peeth and saints,” he added.

Swati Goel Sharma is a senior editor at Swarajya. She tweets at @swati_gs.