Politics

Urban Shift: How BJP Recovered After Lok Sabha Setbacks in Maharashtra and Haryana

Abhishek Kumar

Mar 03, 2025, 01:51 PM | Updated Apr 02, 2025, 02:46 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

How did the BJP (and its allies) perform in the Haryana and Maharashtra Assembly election, in the urban and semi-urban areas that it had lost to the Congress and INDI alliance in the Lok Sabha elections of mid-2024?

This piece compares Assembly segment level data across the Lok Sabha and Assembly elections in an attempt to answer that question.

In the final analysis, it turns out that the BJP and allies benefitted from a wider and more general gains between the Lok Sabha and Assembly elections, than from gains focussed on specific areas by virtue of them being urban or semi-urban.

The Lok Sabha results in June 2024 were a shocker for the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-led National Democratic Alliance (NDA). The coalition, which had begun its campaign with the aim of securing 400 seats, was not even able to secure the majority marker number of 272 seats.

Analysts wrote reports about how urban India—considered a secure voting bloc due to the BJP’s pro-developmental image and Narendra Modi’s face—was losing faith in the party. Some even tried to connect it to communalism and urban India’s dislike of the phenomenon due to its potential to disrupt law and order.

This was despite the fact that the party’s overall vote share in urban areas had risen to 40 per cent—a rise of 6.4 per cent compared to 2019—even as its vote share in semi-urban and rural areas witnessed a decline. One reason behind the attempt to establish such narratives could be the impetus provided by the BJP’s loss in urban seats like Mumbai North Central and Mumbai North East.

Additionally, out of the 92 seats it lost, 63 were non-reserved, which tend to have a higher urban population compared to those reserved for Scheduled Castes (SC) and Scheduled Tribes.

The BJP's performances in Maharashtra and Haryana were put under greater scrutiny since the legislative assembly elections were to be held within a span of six months. The party needed to introspect on its weaknesses in urban areas and come up with a quick fix to avoid further embarrassment.

To begin with the current analysis, the first problem was the availability of accurate and updated data.

Urbanisation is a continuing process, and it is hard to fix any specific parameter around it. For instance, a typical village in northern Indian states lying to the right-hand side (on map) of Delhi in 2011 would have lacked basic road connectivity, medical and educational facilities, financial inclusion, and other necessities of life.

Most of these villages are now connected to main cities through multiple transport networks like buses, autos, and even private cars in case of urgency. Savings habits have also changed due to financial inclusion projects and the availability of medical insurance through Ayushman cards.

Such drastic changes within a span of one and a half decades makes it complex to draw the urban-rural boundary for political and pragmatic purposes. These minor adjustments are also changing voting behaviours and the politics of the day.

For instance, in 2011, jobs would have been preferred as the main source of livelihood for most of rural India, while in 2024, a lot more (though still not more than job seekers) people in rural India prefer to do business compared to 2011. For political parties, this means making promises of credit guarantees in manifestos—especially for women and backward categories of the population.

At the same time, changes in army recruitment rules (read Agnipath) would not have had a big impact on urban India in 2011. However, the October 2024 CSDS-Lokniti survey reveals that for every five Haryanvi voters in rural areas concerned about it, three in urban areas feel the same.

On essential fundamental rights-related issues like schools, hospitals, corruption, women’s safety, and inflation, both rural and urban voters are showing more concerns compared to 2011.

One issue where urban India is expected—if not already—to see an uptick in voting is along demographic and community lines. This could be due to the proliferation of individual social media groups discussing issues of every community—whether related to religion, caste, or sectors in which employees work—over the last decade.

Urban voters, who were not known for participating in agitations unless faced with extreme exigencies, are now seeking more of it.

With these perspectives in mind, it is worthwhile to examine how the voting behaviour of urban and semi-urban voters changed between April-May 2024 and November 2024.

Haryana, Maharashtra, and Jharkhand were the three states that held assembly elections during this period. During the Lok Sabha elections, urban voters in Jharkhand had largely chosen to stay with the BJP. But things were different in Maharashtra and Haryana.

Before that though, let us see how much urbanised both of these states are.

The 2011 Census data shows that Maharashtra’s urbanisation rate was 45.22 per cent, while the corresponding figure for Haryana was 34.88 per cent. Both figures are higher than the national average of 31.1 per cent.

In the wake of big-ticket infrastructure projects, connecting roads, and cheap internet leading to easy access to information, it would be safe to assume that at least a five-percentage-point increase in the urbanisation rate of both states would have been easily achieved.

Due to aforementioned factors, it would be relatively safe to assume that if half of the assembly constituencies of a parliamentary seat fall under urban and semi-urban areas, the overall voting pattern is tilted more towards urban than rural.

Maharashtra

In the 19 Lok Sabha seats of Maharashtra with at least three urban and semi-urban assembly constituencies (out of six), the NDA lost nine of them. These are Dhule, Chandrapur, Mumbai North East, Mumbai North Central, Mumbai South Central, Mumbai South, Nashik, Solapur, and Bhiwandi.

The BJP lost six of these seats, while the Shiv Sena (SHS) lost three.

In these nine Lok Sabha seats, 41 assembly seats fall under the urban and semi-urban category. The NDA’s poor performance in these segments can be gauged from the fact that the coalition trailed in 26—63.41 per cent of the total seats—of them, which also indicates that the Indian National Developmental Inclusive (INDI) Alliance was able to secure more than its national urban average in these seats.

On the six lost seats, the BJP conceded 16 urban and semi-urban assembly constituencies to the opposition, while SHS conceded 10.

Fourteen out of the 26 seats were conceded to the Shiv Sena (Uddhav Balasaheb Thackeray) (SS-UBT), while the Indian National Congress (INC) won ten of them. The Nationalist Congress Party – Sharadchandra Pawar (NCP-SP) won two seats. Remarkably, at the Dhule Lok Sabha seat, Congress’ lead in Malegaon Central was so substantial that it overpowered the BJP’s lead in the other five seats—both urban and rural combined.

The BJP did its homework on these weaknesses, and the results of the Maharashtra assembly elections (AE) 2024 stand as a strong testament to it.

Out of these 41 seats, the NDA decided not to contest Malegaon Central and Shivadi constituencies. At Malegaon Central, a seat with a 75 per cent Muslim population, the alliance had secured 0.75 per cent of the votes in the 2019 AE, while in the 2024 GE, it only managed 4,542 votes compared to nearly two lakhs for Congress.

At Shivadi, the coalition lent its support to Bala Nandgaonkar of Maharashtra Navnirman Sena (MNS). At Deolali, Rajashri Ahirrao of SHS was contesting against Saroj Ahire of the Nationalist Congress Party, making it an intra-alliance contest. Ultimately, despite the coalition contesting only 39 seats, it ended up fielding 40 candidates in total.

When the results came, the NDA reversed the momentum the Maha Vikas Aghadi (MVA)—the Maharashtra chapter of the INDI Alliance—had gained in the 2024 GE.

The Maha Yuti (MY)—the Maharashtra chapter of the NDA—won 29 out of the 39 seats it contested. The BJP maintained its dominance in the alliance with 22 victories, while its partners SHS and NCP won five and two seats respectively.

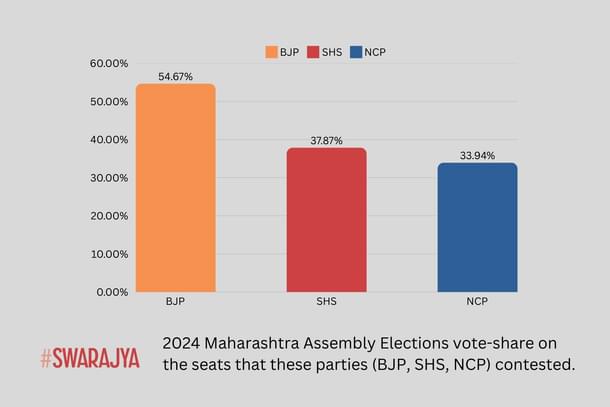

The intra-alliance dominance of the BJP was reflected in its vote share as well. On the winning seats, the BJP’s average vote share was 55.21 per cent—a decisive referendum in light of the fact that at most of these seats, there were more than two candidates in direct contest.

The figure of 55.21 per cent is 11.22 per cent higher than the 44.99 combined average vote share of SHS and NCP on the seven seats they won. Out of these two, SHS performed better with average vote share of 47.13 per cent on five winning seats, while the NCP lagged behind with an average of 39.13 per cent on two seats.

Even on the seats the Yuti lost, the BJP’s performance was far better than that of SHS and NCP. On only one seat (Kalina) it lost, the BJP secured 42.87 per cent of the votes, which brought its overall average vote share down to 54.67. The NCP also lost only the Vandre East seat, but its vote share was just 33.94 per cent. This figure puts the NCP’s total vote share at 37.4 per cent.

SHS lost nine seats—out of which it came second in eight—with an average vote share of only 32.58. The inability to put up a fight in the losing seats brought its overall vote share down to 37.85 from a winning average of 47.34.

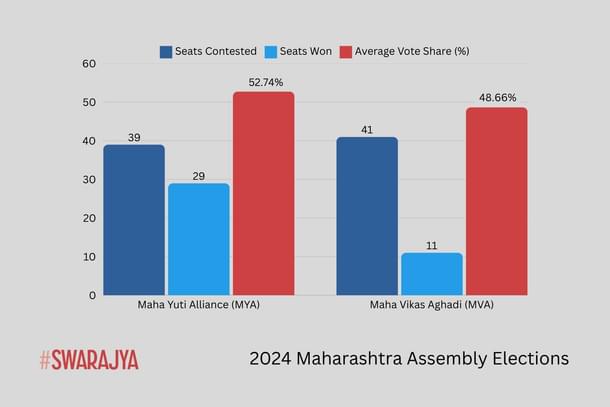

Luckily for the Yuti, the gap between the winning vote share and overall vote share was not that significant. On the 29 seats it won, the Yuti’s vote share was 52.74, while its overall vote share was 47.49. This small spread of 5.25 per cent indicates that most of those who voted for the Yuti did so in the belief that their respective Yuti candidates were going to win.

Comparing the Yuti's AE 2024 performance to the GE 2024, we find that the alliance was able to take back control of 16 seats—Ballarpur (BJP), Warora (BJP), Chandrapur (BJP), Bhandup West (SHS), Ghatkopar West (BJP), Chandivali (SHS), Kurla (SHS), Anushakti Nagar (NCP), Chembur (SHS), Sion Koliwada (BJP), Nashik Central (BJP), Deolali (NCP), Solapur City Central (BJP), Solapur City South (BJP), Kalyan West (SHS), and Murbad (BJP)—out of 26 assembly constituencies where it had trailed in the GE 2024.

On its own, the BJP won back nine of them, but for the remaining seven, it had to rely on its alliance partners, SHS and NCP, which won back five and two seats respectively. The BJP’s single loss was in the Kalina seat, which it had also lost in the GE 2024. The NCP won two seats, namely Anushakti Nagar and Deolali—both of which were important for the comeback of the Yuti.

The BJP giving 16 tickets to its allies in assembly constituencies it lost during the Lok Sabha elections indicates that it had some apprehensions about its prospects in these key seats. Its 90 per cent strike rate suggests that the party was wrong in its assumption, but on the other side of the coin, the allies losing 62.5 per cent of their allotted constituencies highlights that all is not necessarily well.

If the BJP had fielded itself, the possibility of more wins than those accumulated by allies could have been on the cards due to freebies and galvanisation against the perceived rising threat to Hindus.

Fate of its rival, the MVA, tells a different story.

The MVA won only 11 seats of the 41 currently under consideration, with an average vote share of 48.66 per cent—4.08 per cent less than the Yuti's winning vote share. SS-UBT emerged as its top performer, with seven victories, bagging an average vote share of 46.31 on winning seats—8.90 per cent less than the corresponding figure for the Yuti’s top performer, the BJP.

The other two parties, namely the Congress and NCP-SP, won two seats each with an average vote share of 58.61 and 46.91 per cent respectively.

SS-UBT lost in 13 seats with an average vote share of 29.74 per cent on the losing seats. This was 2.84 per cent less than the losing vote share of SHS, the party that conceded the most seats in the Yuti. The Congress lost from 10 seats with a losing vote share of 27.67, while the NCP-SP’s loss on six seats came with a losing vote share of 31.51 per cent.

On the two seats the NCP-SP lost, its vote share was 12.71 per cent, which indicates that it was nowhere in the fight.

The MVA’s average vote share on losing seats was 29.10 per cent, 4.54 per cent less than the corresponding figure for the Yuti at 33.64 per cent. In terms of overall vote share (on both winning and losing seats), the MVA secured 33.63 per cent, while the Yuti obtained 47.49 per cent.

These two data points indicate that in the 41 seats under consideration, the Yuti not only heavily dominated the seats it won but was also an extremely tough challenger on the seats it lost. This is also corroborated by the Yuti having more victory margins in double-digit percentages. While Yuti allies frequently won with more than a 20 per cent lead, the MVA struggled to lead by more than 10 per cent on many of the seats it won.

BJP in Haryana

In Haryana, however, which polled around two months before Maharashtra, the story was slightly different.

In GE 2024, the party lost five seats in the state - namely Ambala (SC), Sirsa (SC), Hisar, Sonipat and Rohtak. At Rohtak and Sirsa, it was completely decimated, while in the other three seats, the party was able to put up some fight.

On these five parliamentary constituencies, 20 assembly constituencies can be broadly categorised under urban and semi-urban categories. Eleven out of these 20, namely - Ambala City, Jagadhri, Sirsa, Tohana, Narwana, Nalwa, Garhi-Sampla Kiloi, Rohtak, Kalanaur (SC), Bahadurgarh and Gohana - gave the INC a lead over the BJP in the General Election in 2024.

These results were considered a sign that there was a huge anti-incumbency wave in Haryana against the BJP, and the Hooda faction-led Congress would sweep the assembly elections. However, the Congress lost the plot midway and conceded a hard-gained victory to the BJP.

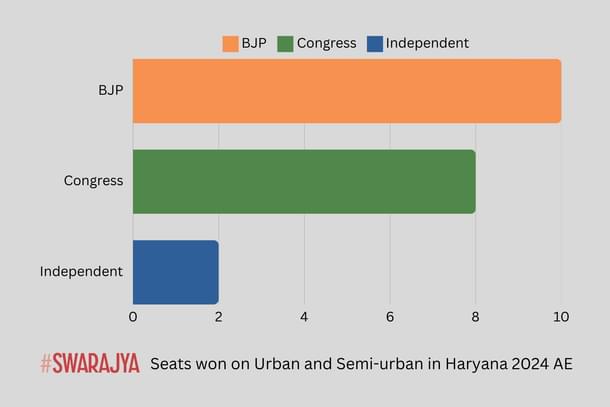

In the Assembly elections of October 2024, on these 20 semi-urban and urban seats, the BJP won ten of them with a winning vote share of 47.56 per cent, which is not a handsome margin, as reflected by the fact that it is less than the Congress’ winning vote share.

On the nine seats that the BJP lost, its average vote share was 34.98 per cent. However, this figure was significantly skewed by large deficits, which included a 28.31 per cent gap in Hisar (where Savitri Jindal won as an Independent), a 47.88 per cent gap in Garhi Sampla-Kiloi (won by Bhupinder Singh Hooda), and a 26.39 per cent gap in Bahadurgarh (where Independent candidate Rajesh Joon emerged victorious).

Barring these big losses - inflicted mainly due to the regional dominance of particular leaders - the party remained competitive in other seats.

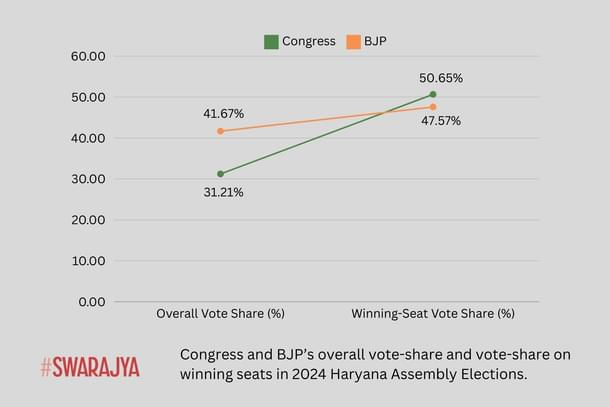

The BJP’s overall (on both winning and losing seats) vote share was 41.67 per cent. Out of the 11 seats it trailed in GE 2024, the party won three of them, namely Gohana, Narwana and Nalwa. However, the BJP also lost Panchkula and Hisar - two seats in which it was leading in the Lok Sabha elections.

Its rival Congress, on the other hand, won eight out of the 20 seats it contested, with an average winning vote share of 50.65 per cent - 3.09 per cent more than the BJP’s winning vote share. However, this number has a tinge of regional politics-based inflation in it. The overall winning vote share of the Congress is skewed by Bhupinder Singh Hooda’s massive victory of 47.88 per cent margin in the Garhi Sampla-Kiloi seat.

Removing this outlier, Congress’ adjusted winning-seat average drops to 47.49 per cent, putting it nearly at par with the BJP’s 47.57 per cent on its winning seats. Hooda’s impact on the overall vote share can be gauged from another fact: outside Hooda’s seat, Congress' most comfortable victories came in Kalanaur and Ambala City, where its margins were 8.54 per cent and 6.62 per cent respectively, but none approached the scale of the BJP’s largest margins.

The BJP’s highest victory margins were in Sonipat (19.46 per cent), Barwala (19.24 per cent), and Hansi (15.8 per cent), which looks more evenly distributed compared to the Congress.

The Congress losses also tell a similar story. It lost 12 seats with an average vote share of 31.21 per cent - 3.77 per cent less than the BJP’s losing-seat average. In terms of overall vote share, the INC, with 38.98 per cent, trailed 2.69 per cent behind the BJP, which secured 41.67 per cent of the total votes polled on urban and semi-urban seats in the Lok Sabha constituencies where the BJP lost.

Looking at the broader trends, the BJP’s winning-seat vote share (47.57 per cent) was 5.90 per cent higher than its overall vote share (41.67 per cent) in Haryana, whereas in Maharashtra, its winning-seat vote share was 55.21 per cent, which is just 0.54 per cent higher than its overall 54.67 per cent.

The Congress’ winning-seat vote share (50.65 per cent) was 19.44 per cent higher than its overall vote share of 31.21 per cent, suggesting that Congress' victories were concentrated in a few strongholds where it performed exceptionally well, but outside these strongholds, the struggle was quite significant.

In Maharashtra, the MVA’s winning-seat vote share of 48.66 per cent was also 15.03 per cent higher than its overall vote share of 33.63 per cent, while for the BJP-led Yuti, this gap was just 5.25 per cent.

The more even distribution of winning votes for the BJP and its allies indicates that the support for the party was more even across the urban and semi-urban constituencies of Haryana, while for the Congress, it came in pockets with high intensity but less stability.

Just as in Maharashtra, the Congress in Haryana lacked emphatic victories outside of a few strongholds and performed especially poorly in seats where it lost. In both states, the BJP remained competitive in most constituencies, even when on the losing side, while the Congress failed to maintain a similar level of resilience.

Abhishek is Staff Writer at Swarajya.