Politics

CAA's Tortuous Journey And The Perils Of Giving In To A Minority Street Veto

R Jagannathan

Mar 12, 2024, 11:58 AM | Updated 11:58 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

When a law passed by Parliament in 2019 gets to the implementation stage only now, it is important to ask: will the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) get properly implemented even now, both in letter and spirit?

Already, the chief ministers of two states, Kerala and West Bengal, have opposed the CAA, and Assam and the North East are bitterly divided on it.

The latter believe that the National Register of Citizens (NRC) is more relevant to them in order to maintain an ethnic demographic edge vis-a-vis “outsiders”.

A little bit of recent history will give us pointers on the CAA’s prospects in the coming months. The CAA was halted in its tracks almost immediately after it was legislated as Muslims protested violently on the streets, vociferously supported by politicians dependent on the minority vote.

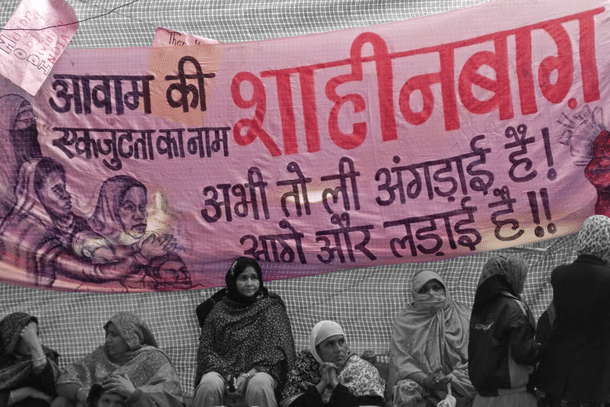

The Shaheen Bagh road blockages told us how far the government was willing to go to avoid a confrontation with the minorities on the streets. It ended only when Covid-19 made it easier for the law and order machinery to clear the protest site.

Put simply, when one side is willing to resort to violence and intimidation to get its way, we must wonder how far the government will go with CAA beyond symbolism even though the rules have now been framed.

The law, which is intended to fast-track citizenship for persecuted minorities from Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan who entered India before 31 December 2014, is a half-measure.

Reason: the persecution of Hindus, Sikhs and other minorities has not ended. Why have a law which only clears a small backlog from the past, but will let minorities continue to suffer in future in these Islamist states and/or theocratic societies?

Another truth needs acknowledgement: the subliminal reason why Muslims oppose CAA is that it would amount to an acknowledgement that their own Umma is persecuting Hindus in their neighbourhood. In Islam, and in Christianity, the persecution and martyr complex is vital for building aggression within the community against non-believers.

The CAA, which seeks to shatter the myth that Muslims are persecuted everywhere, is thus a direct threat to their ability to bring crowds on the streets and intimidate non-Muslims into giving them what they want, whether it is reasonable or not. This is the same reason why no Muslim of consequence is willing to accept evidence they can see in front of their eyes — that many mosques are built over Hindu places of worship.

Now let us see how the CAA finally came to be brought to the execution stage today. In the last four years, the government first gave the (reasonably genuine) excuse of Covid to delay framing the rules under CAA. Covid effectively ended two years ago, but the government still dilly-dallied till three months ago.

The opposition believes that this was done for two reasons: one is to take the headlines away from disclosures on who got how much from which corporates in the form of electoral bonds; and, two, to enable the BJP to make an impact in West Bengal, where several migrant Hindu communities from Bangladesh see this as a beacon of hope for them.

Even assuming these two criticisms are valid, the real reason why CAA rules came so late, and that too so close to the announcement of election dates, is something else. There is deep anxiety in government about the Muslim-secular ability to organise an effective resistance to it on the streets.

With elections being announced, this cannot happen, as law and order is subject to Election Commission jurisdiction. The late announcement of CAA rules plays a role similar to what Covid and the Delhi riots did to help the government end the Shaheen Bagh protests after February 2020.

The simple reality, which will never be said aloud, is the government does not want another faceoff on the streets right now. It is hoping that a strong performance in the Lok Sabha polls will give it the political heft to see off this street challenge, as and when it happens.

Some plain truths are worth stating. The CAA is the minimum needed to assure Hindus in the neighbourhood that India can be counted upon to bat for them. The real remedy is to have an open-ended right to return for any persecuted Hindu, Jain, Sikh or Buddhist of Indian origin, just as the Jew has with respect to citizenship of Israel.

The right to return has to be hard-coded into the Constitution which is effectively unable to protect Hindu interests in India, leave alone in the neighbourhood. As the only country with a substantial Hindu population, the case for a Hindu Rashtra that can defend Hindu rights anywhere is strong as ever.

Otherwise you cannot fight a well-oiled global Umma or the Christian-secular alliance against Hindu India. CAA is just the first test of the BJP’s ability to forge a larger coalition of Hindu castes and communities to fight for equal rights. If it fails with CAA, it will fail in the larger goal, too.

Here's the irony of it all. A law to help persecuted Hindus and minorities is itself subject to unlawful attacks and blackballing through the exercise of a minority street veto. A law which cannot defend itself is no law at all.

Jagannathan is former Editorial Director, Swarajya. He tweets at @TheJaggi.