Politics

Hostile Takeover: Andhra Government’s Misguided Attempt To Control Ahobilam Temples Comes To Light

Vivek Rallabandi

Dec 25, 2019, 06:20 PM | Updated 06:43 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

In Andhra Pradesh’s Kurnool District, amidst the picturesque Nallamala Hills, lies an important spiritual centre: Ahobilam.

The nine temples of Narasimha located in the temple town draw pilgrims from throughout the state and beyond.

Ahobilam is also home to the Sri Ahobila Math, a religious seat that adheres to the Srivaishnava tradition. The math, which has a history dating back over six centuries, is inextricably linked to the Ahobilam temple.

In 1398 CE, the first mathadhipati, or head of the Ahobilam Math, Srimad Adivan Sadagopan, was initiated into monasticism by the deity, Sri Lakshmi Narasimha, in Ahobilam.

The deity bestowed on Sri Adivan Sadagopan an idol of Malola Lakshmi Narasimha, with a command to travel with it from village to village and propagate devotion to the Lord.

For centuries, it was the Math that was at the helm of the Ahobilam temples, controlling their administration and finance.

Authority on temple affairs lay with the jeers of the Math, the monastic successors in the lineage of the first mathadhipati.

Over the years, the Math has preserved the temples of Ahobilam and their traditions through thick and thin.

For instance, according to inscriptions found in the Ahobilam temple, the sixth jeer of the Ahobilam Math, with the help of the Vijayanagara king and the Telugu Chola chieftain, was able to renovate the temple in 1579 CE following an Islamic invasion.

Over the centuries that it managed the temple, the Math never faced any governmental overreach in its affairs. In 1989, the Andhra Pradesh government requested the mathadhipati to appoint his own disciple as manager of the temple.

In 2001, the then-Endowments Minister of Andhra Pradesh, Dandu Sivaramaraju, stated on the floor of the Legislative Assembly that it was legally not possible to override the authority of the mathadhipati by appointing an executive officer above him.

In 2008, the government promoted the math-appointed manager of the temple to the position of executive officer.

Eventually, the government began to appoint executive officers of its own accord without the knowledge of the mathadhipati, though there is no clear record of when this practice began.

Legally Tenuous

The legality of the Andhra Pradesh Endowments Department’s involvement in the temple’s affairs is in and of itself questionable.

A question arises as to whether the temple was even taken over officially by the state government.

Kidambi Sethu Raman, a descendant of the first Ahobilam mathadhipati, and whose family has been in the service of the math for generations, filed an RTI query with the Endowments Department to find the answer to this seemingly simple query.

The reply from the temple’s Executive Officer is astonishing: there is no government order on file that documents the temple coming under the aegis of the government.

Considering the declaration of the Endowments Minister himself in 2001 that there was no legal way to appoint an Executive Officer above the mathadhipati, it appears that the state government usurped control of the temple illegally.

In an interview, Kidambi noted that a formal transfer of authority to the government would have entailed a handover by the mathadhipati of the temple properties, lands, and accounts.

He questioned how the Endowments Department could have assumed control of the temple without any such procedure.

Furthermore, the present classification of the temple is under Section 6a(ii) of the Andhra Pradesh Charitable and Hindu Religious Institutions and Endowments Act (Endowments Act), which explicitly refers to “religious institutions and endowments other than maths.”

The temple is virtually indistinguishable from the math — according to a governmental inquiry in 2018, “the entire administration of the temple is under the control and hold of the Peetadhipathi from the time immemorial.”

A physical example of the timeless link between the Math and temple is the fact that carvings on the wall of the Ahobilam temples actually display the Hamsa mudra, or swan emblem of the Ahobila Math (see photo above).

The emblem was given to the first mathadhipati by the Srivaishnava saint Nammalwar, under whose name the temple is administered to this day.

Considering the virtual inseparability of the temple and math, it is quite surprising that the government used this provision to take control of the temple.

Financial Mishaps

To obtain a better understanding of the Endowments Department’s involvement in Ahobilam, it’s important to take a look at the temple’s finances.

According to Kidambi, the temple maintains an account in the Andhra Bank’s Ahobilam Branch in the name of the deity, with the mathadhipati being the principal account holder.

In order to release money from the account, the mathadhipati signs cheques with the title “Sri Sadagopa Sri” — a reference to Nammalwar — displaying the unbroken link the temple has to the math and to the Srivaishnava tradition.

The money spent by the temple is contained in a budget prepared annually by the temple’s Executive Officer and approved by the Commissioner of Endowments.

Through an RTI request, Kidambi was able to obtain copies of the temple’s budget for the years 2016, 2017, and 2018. A careful study of the budget reveals some alarming details about the spending of the deity, Lord Narasimha’s money.

In the 2016 budget, Rs 18,50,000 was sanctioned for the 2016 Krishna Pushkarams, a religious festival that takes place once every twelve years in and along the Krishna River.

Temples along the Krishna River would have made extra arrangements to accommodate the devotees coming for the Pushkarams.

The surprising thing is, however, that Ahobilam is not located along the Krishna River — in fact, it’s nowhere close. (See the map above.) This certainly raises questions about why this amount was sanctioned.

Another area of concern is the budget allocation for Hindu Dharma Pracharam, or propagation of Hindu Dharma.

The amounts sanctioned for this purpose — Rs 8 lakh in 2016, and Rs 12 lakh in 2017 and 2018 — are certainly not trifling.

Kidambi notes that no pamphlets or other religious materials were issued by the temple in any of these three years.

Even though the 2017 and 2018 sanctioned amounts include money for Divya Darshanam (a programme to provide free darshan to SC, ST, BC, and economically backward pilgrims), it is still a surprise that no efforts in the vein of dharmic awareness were undertaken by the temple despite the sanctioned amount.

Furthermore, the charges for the Executive Officer’s car, which add up to almost Rs 9 lakh over three years, also raise alarm. Kidambi notes that with this amount, a new car could have been purchased for the devasthanam.

The issue of contributions from the temple treasury to the Endowments Department is also a cause for concern.

Under Section 65 of the Endowments Act, each temple needs to make a certain contribution annually to the Department for administrative purposes based on its annual income, which is determined through an audit.

The issue here, though, Kidambi points out, is that the last official audit carried out by the government was for the 2006-07 fiscal year.

He noted that though the math has been carrying out annual audits, the government has not been auditing the temple treasury on its end.

Kidambi questioned how the government could allocate Rs 40-50 lakh rupees per annum (as shown above) as contributions without a proper audit.

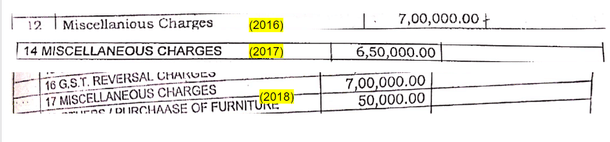

Lastly, the budget for all three years lists amounts under “miscellaneous charges,” which add up to Rs 20,50,000. After the preparation of such a detailed budget (it had 71 individual items in 2016), one can only wonder what other miscellaneous charges would require this mammoth expenditure.

All of these issues with the budget raise this question — why was the Commissioner of Endowments rubber-stamping the Executive Officer’s budget proposals without due examination?

The Commissioner should have certainly questioned the reasons for certain expenditures, such as the Krishna Pushkarams, before approving them.

It is chilling to imagine how these massive amounts of the Lord’s money were spent by the Executive Officer and other endowments officials.

In contrast, the mathadhipati and the Ahobila Math’s costs are not borne by the temple treasury, according to an RTI query filed by Sh. Kidambi.

As such, Sh. Kidambi noted that allegations that the mathadhipati is squandering the temple’s funds are completely disproven and baseless.

The temple appropriations proposed by the Executive Officer and approved by the Commissioner for these three years, Kidambi noted, were not approved by the mathadhipati.

Section 57 of the Endowments Act requires that the temple’s trustee prepare the annual budget and forward it to the Commissioner for approval.

As the Ahobilam devasthanam does not have a non-hereditary trust board, the power of trusteeship lies in the hands of the hereditary trustee, the mathadhipati.

However, Kidambi pointed out that the mathadhipati had not even received a courtesy copy of the annual budgets from the Endowments Department.

Instead, Kidambi explained, the Executive Officer routinely approached the Mathadhipati, requesting money for administration of the temple.

The Mathadhipati, who has the power to issue cheques, was forced to sanction the requested amount in order to facilitate the smooth running of the temple.

This practice by the Endowments Department, which completely cuts the mathadhipati out of the temple’s finances, is a flagrant violation of the law.

Religious Meddling

Not satisfying itself with financial affairs alone, the Endowments Department also began to poke its head into the temple’s religious affairs. Kidambi narrated the experience of his own uncle, who was working as a paricharika in the Ahobilam temple and received retirement orders from the Endowments Department.

The Executive Officer asserted that since religious employees were receiving pay under government PRC scales, they were under the control of the government.

The mathadhipati asserted, however, that religious employees were linked with the math and not the government, and therefore, the government had no authority to control them.

In February of 2019, the Endowments Department issued an order sanctioning the creation of a new post in the archaka (priest) cadre.

Kidambi, who wrote to the Commissioner voicing his strong objection to the government’s intervention in religious matters, questioned how the government was qualified to appoint priests when it had no knowledge of the traditions and customs of Ahobila Math.

The government also took a bold decision in 2014, when it attempted to remove the mathadhipati from his position as hereditary trustee of the temple by constituting a non-hereditary trust board.

After receiving strong pushback and being reminded that the decision was illegal under Supreme Court precedent, the government stepped back from its attempt to establish a trust board.

Another recent decision by the government was the removal of the prefix “Sri Ahobila Math Paramparadheena” from the name of the temple.

This prefix signified that the temple had an age-old association with the Ahobila Math.

Amending the temple’s name to “Sri Lakshmi Narasimha Swamy Devasthanam” is without doubt an attempt to isolate the Math from the temple and obliterate the centuries-long history the two institutions share. (The Endowments Department temple website continues to omit the prefix).

To The Courts

The government’s repeated attempts to usurp control of the Ahobila Math were condemned by the mathadhipati and math authorities, who sent repeated letters to the Commissioner expressing their concerns on various issues.

All of their pleas, however, fell on deaf ears, and no action was taken.

As a last resort, the mathadhipati resolved to file a case in the Andhra Pradesh High Court in April 2019 challenging the appointment of an Executive Officer to manage the Ahobilam temple.

In the same month, the High Court issued interim orders, which were further extended in June, giving the math control over the temple’s financial affairs.

As the case is heard in court, disciples of the Ahobila Math, such as Dr. MV Soundararajan of the Temple Protection Movement, have appealed to Chief Minister Hon. Y.S. Jagan Mohan Reddy to cease interfering in the operations of the Ahobilam temple.

So far, it seems that there has been no action based on these pleas to the government.

A Final Word

It is up to us as Hindus to rise up and protect our temples from heavy-handed government action.

When observing the injustice that is being done to a storied spiritual centre like the Ahobila Math, we cannot remain quiet and stay in the shadows.

As Kidambi observed, “If we do not protect the Ahobilam temple today, we can never protect any of our Hindu temples or institutions.”

As we lie at this crucial crossroads, we must remember the age-old maxim, Dharmo Rakshati RakshitaH — dharma, only when protected, protects us.