Ground Reports

In Gurugram Slum, Residents Unaware Of Inmate Arif's Hand In Anti-Muslim Hate Posters Falsely Linked To Bajrang Dal, Say Never Took The Threats Seriously

Swati Goel Sharma

Oct 02, 2023, 12:05 PM | Updated Oct 09, 2023, 02:24 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

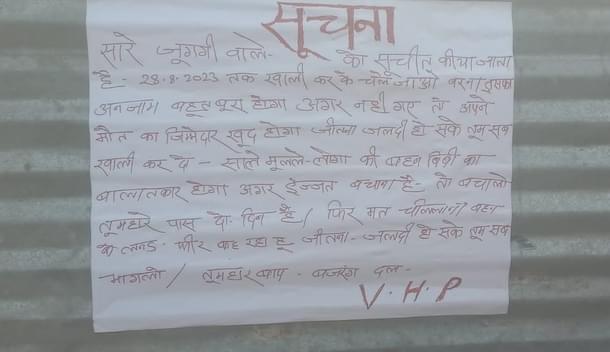

In a slum settlement in Gurugram, a bustling town on the outskirts of Delhi, two posters mysteriously surfaced about a month ago, asking the predominantly Muslim residents to vacate the area permanently.

The hand-written posters ominously warned the Muslim inhabitants of rape and murder.

They were signed in the name of VHP, an acronym for Vishwa Hindu Parishad, a well-known Hindu organisation, and its youth wing Bajrang Dal.

This alarming development followed close on the heels of communal violence that had erupted in the region, stemming from an attack on a Hindu religious procession in the Muslim-majority Nuh (earlier Mewat) district.

The attack resulted in the immediate deaths of two home guards. The flames of violence had spread to Gurugram the following day, leading to two casualties—one Hindu and one Muslim.

As the dust settled, the police's investigative efforts have unravelled a shocking twist.

Contrary to initial suspicions, a VHP operative was not responsible for the menacing posters. Instead, the culprit has been identified as Mohammed Arif, a resident of the slums.

According to police, Arif orchestrated the fear-mongering with the intention of exploiting the ongoing tensions to eliminate competition in his scrap trade.

In a ground visit to the colony this week, which is located opposite Tulip White society in sector 69 of Gurugram, Swarajya found that only a few residents knew about the police revelations.

Most residents continue to believe it to be the handiwork of Hindu organisations.

However, they say that they never considered the threats as serious. They did temporarily migrate out of the slums, staying with relatives or friends nearby, but returned after a week or two.

The inhabitants were reluctant to speak further, saying the tensions had long subsided and that Hindus and Muslims in the area were living peacefully as ever.

In this settlement of about 3,000 migrant families, only about 10 or 15 families are Hindus.

Interestingly, despite their self-identification as "Bengalis," the colony is commonly referred to as the 'Bangladeshi colony' by locals.

This nomenclature came to light during a conversation with an autorickshaw driver who transported this correspondent from the Millennium City Centre metro station.

The driver, hailing from Uttar Pradesh, casually alluded to the area as 'Bangladeshi colony’. We learnt that street vendors, too, referred to the colony by this name.

After much persuasion, a group engrossed in a card game agreed to talk. When asked about the site where the posters were put up, a man named Shazeem said two posters had been pasted on two adjacent shops.

The first of these establishments, a junkyard, belonged to Mojeed, which has since been demolished by the police. While the other, a grocery shop, is operated by a woman cryptically referred to as 'thekedarni' by residents.

Shazeem admitted that her actual name remained a mystery, but she functioned as a contractor for the landowner, who is known simply as 'panditji.'

She charged a monthly fee of Rs 1500-2000 for each shanty or shop within the slum enclave.

When this correspondent tried to talk to the thekedarni regarding the slums, she hurled a torrent of profanity while promptly withdrawing from the scene.

Mojeed dealt in scrap, and so did Arif. Beyond that, the residents possess scant knowledge about them. Following the incident involving the posters, the police scoured the slums on three separate occasions within a week to apprehend Arif, but he eluded capture.

Eventually, when the authorities did manage to catch him, they subsequently released him after three to four days.

Arif, together with his family, has now vacated the slums and relocated to an undisclosed location. "No, he won't return to this colony," affirmed Shazeem.

Mojeed, they said, has not returned to the colony since the poster controversy.

When inquired about their places of origin, the group said that nearly the entire colony hailed from West Bengal's Malda district. Economic opportunities had driven them to migrate to Gurugram.

Recalling the events of the day, 27 August, when the incendiary posters appeared, Jahangir, who drives an autorickshaw, said a stir erupted when a few residents observed the posters, though none among them could decipher the Hindi script.

They brought a local rickshaw puller to decipher the content.

Soon, a wave of panic spread in the area. By afternoon, law enforcement officers had arrived and removed the offending posters.

Jahangir added that certain Sangh activists also made an appearance, offering assurances that no harm would befall them.

Jahangir said the threatening posters were 'anticipated', as a reaction to the earlier Nuh violence. Within the next two days, almost all Muslim families vacated, leaving only a handful of Hindu families behind.

Umanand Pathak, a Hindu resident employed at a nearby residential complex, corroborated the account of temporary migration. "I knew they would all return. There is no issue here. Everyone lives peacefully. Minor threats following the incidents in Mewat are expected," he asserted. Pathak, too, remained unaware of the police revelations regarding Arif.

(Note: The ground visit was made by Swarajya intern Aryan Tripathi. The report has been written by Swati Goel Sharma based on his inputs)

Swati Goel Sharma is a senior editor at Swarajya. She tweets at @swati_gs.