Science

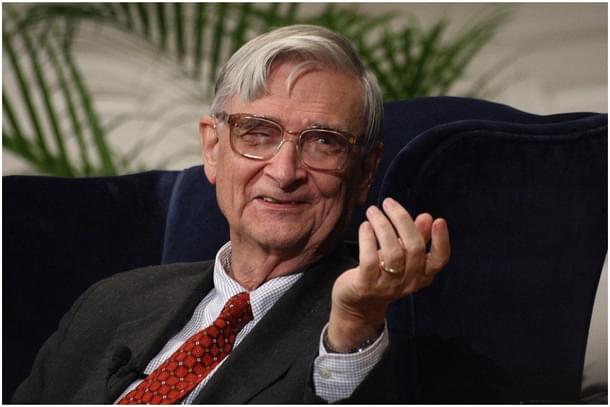

Edward O Wilson (1929-2021): The Fearless Biologist

Aravindan Neelakandan

Dec 28, 2021, 08:38 PM | Updated Dec 31, 2021, 08:43 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

The young speaker, the last on a list in a science conference, had his right ankle ina cast and was using crutches. He had to deliver his address sitting. As he started, suddenly, some youths rushed to the stage chanting slogans and insults ‘Racist you cannot hide; we charge you with Genocide.’ A group of students started shouting with placards against the speaker. The leader of the group rushed to the lectern.

The moderator of the panel, a seasoned anthropologist, told the protestors to stop and pleaded with them ‘I am also a Marxist.’ As if on cue, a woman protestor standing behind poured a pitcher of ice water on the head of the speaker who had just started speaking. An eye witness described the event later as ‘the most hateful, frightening, disgusting behavior I’ve ever witnessed at an academic assembly.’

The speaker was Edward Wilson – a natural scientist who studied ants and created the basic framework for sociobiology. The conference was that of American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). With ice-water poured on his head, forced to sit because of his already injured leg, Wilson proceeded to read ‘Trends in Sociobiological Research’ even as the protestors indulged in slogan chanting to humiliate him: ‘Wilson, you are all wet!’

Edward Wilson had seen life at its toughest, right from childhood. His chosen field was entomology – particularly the ants. His inspiration was ethologist Konrad Lorenz. Wilson slowly moved away from the usual work of taxonomic classification of ants to the study of their behaviour through ingenious methods.

He worked with fire-ants society for which he created artificial nests. He studied their way of communication about food locations to fellow worker ants. The communication was through odour and through exhaustive source of microdissections he discovered the gland that secretes the chemical which provides the odour-based communication of the location of food. These body of chemicals are the pheromones.

Today, we know that pheromones are employed by insects for communication as well as for sexually attracting the opposite sex. Pheromone traps are one of the ecologically better ways of pest control in agriculture.

From the social behaviour of insects, which very much had genetic component in them, he moved on to human societies.

In 1975 he published the book The Sociobiology the New Synthesis. Even while dealing with insect societies, Wilson made the following observation:

In spite of the phylogenetic remoteness of vertebrates and insects and the basic distinction between their respective personal and impersonal systems of communication, these two groups of animals have evolved social behaviors that are similar in degree and complexity and convergent in many important details.

The book on sociobiology was a sequel to this observation. Academics with Marxist orientation led by Marxist ‘dialectical biologist’ Lewontin went far beyond academic criticism. Wilson was called names and labelled as racist and his lectures were threatened and disrupted by left-wing student unions.

Even now, The Guardian claims in his obituary that Wilson took ‘all human behavior a product of genetic predetermination, not learned experiences.' This is a gross caricatured misrepresentation. E.O.Wilson, in the preface he wrote to the 25th edition of ‘Sociobiology’, explains:

The objective meaning of human nature is attainable in the borderland disciplines. We have come to understand that human nature is not the genes that prescribe it. Nor is it the cultural universals, such as the incest taboos and rites of passage, which are its products. Rather, human nature is the epigenetic rules, the inherited regularities of mental development.

Wilson’s study of religion in the sociobiological framework is fascinating, though Western-centric. In his works, religion comes out mostly as a phenomenon related to human groups. While himself a scientific materialist, he had sympathy for traditional religion, while none for Marxism. He had seen Marxism in full plumage with all its anti-science attitude. His evaluation of Marxism in this regard hits the bullseye in describing the problem Marxism has with science:

Marxism is sociobiology without biology. The strongest opposition to the scientific study of human nature has come from a small number of Marxist biologists and anthropologists who are committed to the view that human behavior arises from a very few unstructured drives. They believe that nothing exists in the untrained human mind that cannot be readily channeled to the purposes of the revolutionary socialist state. When faced with the evidence of greater structure, their response has been to declare human nature off limits to further scientific investigation.

Though a scientific materialist, he saw process theology and Deist tradition as the best possible pathways for Western religion to move into in the future. While the Marxists in their ideological vested interest called him a crypto-racist, Wilson was not. He was a scientific materialist and battle-hard evolutionist who was moved to tears in 1984 when the gospel choir sang after a sermon by Martin Luther King's father at Harvard.

Seeking truth and genuine dialogue in pursuit of truth is a trait beyond political vested interests.

E. O. Wilson showed it in his life.

Perhaps the behaviourist school of B F Skinner could be considered as the farthest-away conception of human nature from that of E. O. Wilson. For Behaviourism it is the environment that played a decisive role in the human nature. For sociobiology the genes and culture coevolved. But both these scientific giants in the field respected each other and in 1987 (three years before Skinner’s death) they had a wonderful dialogue on their worldview.

Skinner’s daughter, Julie Vargas, in her introduction to the book E.O. Wilson and B.F. Skinner: a Dialogue Between Sociobiology and Radical Behaviorism remarked:

My father, B. F. Skinner, had a very high regard for E. O. Wilson both as a scientist and as a person. The two men had much in common. Skinner’s discoveries, like those of Wilson, had arisen from direct observation of life processes in action. Both scientists got their hands dirty. Neither was an armchair philosopher, but both saw the implications of the scientific principles they were observing. … Since the origins of the two fields in the twentieth century, the fields have progressed in their own spheres with as little interaction between them as between their founders. Increasingly that isolation is being called into question. It is now clear that all life forms on earth are interconnected and that behavior, human or ant, is a product of interactions of life forms within their world. Even the genes that are “turned on” during development depend on environmental variables that, in turn, are affected by the behavior of each species. Further consilience between the biological and behavioral sciences would advance both.

In 1980 Wilson became interested in the problems of ecology as he could sense that the planet was moving towards a global environmental crisis.

He wrote about Biophilia, which he defined as ‘the rich, natural pleasure that comes from being surrounded by living organisms.’ Wilson embraced the vision of Gaia and pointed out the insignificance of humans as a species in the face of the planet:

The truth is that we need invertebrates but they don’t need us. If human beings were to disappear tomorrow, the world would go on with little change. Gaia, the totality of life on earth, would set about healing itself and return to the rich environmental states of a few thousand years ago. But if invertebrates were to disappear, I doubt that the human species would last more than a few months. Most of the fishes, amphibians, birds, and mammals would crash to extinction about the same time. … Within a few decades the world would return to the state of a billion years ago, composed primarily of bacteria, algae, and a few other very simple multicellular plants.

He brought focus on the word Consilience and wrote a book with same title. This is essentially a samanvaya between the religion of the West and the science with its scientific materialism. While recognizing the need in humans for a grand sacred narrative, Wilson thinks of a harmony benefitting both science and religion. He wrote:

People need a sacred narrative. They must have a larger purpose, in one form or other however intellectualized. They will refuse to yield to the despair of animal mortality. They will continue to plead in company with the psalmist, Now Lord, what is my comfort? They will find a way to keep the ancestral spirits alive. If the sacred narrative cannot be in the form of a religious cosmology, it will be taken from the material history of the universe and the human species. That trend is in no way debasing. The true evolutionary epic, retold as poetry, is as ennobling as any religious epic.

So, if the conventional religion cannot live up to the vision of the universe that science unveils by updating and adapting its sacred narrative then science should be made to provide the same sacred narrative through its vision of grandeur, which Wilson also pointed out was far richer than all the religious cosmologies put together. But this shall not be a cult of reason Western enlightenment-era style:

On the one side ethics and religion are still too complex for present-day science to explain in depth. On the other, they are far more a product of autonomous evolution than hitherto conceded by most theologians. Science faces in ethics and religion its most interesting and possibly humbling challenge, while religion must somehow find the way to incorporate the discoveries of science in order to retain credibility.

Religion will possess strength to the extent it codifies and puts into enduring poetic form the highest value of humanity consistent with empirical knowledge. … The eventual result of the competition between the two world views, I believe will be the secularization of the human epic and of religion itself. However, the process plays out, it demands open discussion and unwavering intellectual rigor in an atmosphere of mutual respect.

The words ‘open discussion and unwavering intellectual rigor in an atmosphere of mutual respect ‘ actually provide the basis for samanvaya process in the context of science and religion. And this also opens up the space for civilizational dialogue for Hinduism with science.

It is really a pity that Wilson never studied the Hindu religious phenomena as an evolutionist. Today, with the development of neurotheology, the present generation Hindus can perhaps come out with serious advancement in this field by applying Darwinian principles to the phenomenon of our religion.

As one can see what Wilson has written is mostly for Western religion and universal science. The Hindu-Buddhist religious universe is already more symbolic and inner-experience-based than the theology and creator-oriented Western religious landscape. But will the modern Hindu scholars and institutions realize the importance of what Wilson had stated and position Hinduism to meet these challenges is the question.

A 92-years-old man passing away is almost expected. Yet in his passing away, an important chapter in the saga of human understanding of evolution comes to a close. May his memory, as a scientist who spoke truth in the face of physical assault and threat of academic isolation, as an ecologist who cared for the planet and above all a wonderful human being, inspire the next generation of biologists to continue the chapter from where he has left it.

Aravindan is a contributing editor at Swarajya.