World

Biden’s Big Gamble: Broadside Against Big Oil, Releasing Strategic Reserves. Can President Tame Soaring Energy Prices?

Venu Gopal Narayanan

Nov 25, 2021, 09:04 PM | Updated 09:04 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Analysing current events is all about connecting seemingly-unconnected dots, so that the actual picture emerges. So what is one to make of tapering crude oil prices, news that major oil consumers, including India, would be releasing stock from their strategic oil reserves, an apparently-tepid summit meeting between American President Joe Biden and his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping, and record inflation in America?

Data analysis by Swarajya shows that these events, plus others, are closely interlinked. They point towards a period of economic turbulence in America, which would have an impact on different parts of the world in different ways.

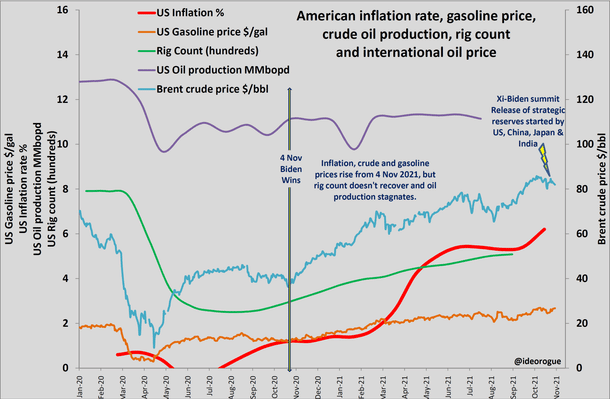

The principal findings are: rising gasoline prices in America have caused inflation rates there to reach 6.2 per cent this month – the highest since 1990; economic recovery in America, which should have ridden on the back of increased activity in the domestic petroleum industry, hasn’t happened; American oil production has stagnated, and the rig count is still well down.

America, along with the other largest oil consumers, are therefore releasing stocks from their strategic petroleum reserves to try and reduce the oil price; and most importantly, most of these developments began after Biden won the presidential elections in November 2020.

This is a pretty pickle Biden finds himself in. It has widespread ramifications, because the conclusion is that he needs to reduce inflation by reducing gasoline prices, do that by trying to reduce international crude oil prices, while trying to boost the American economy by increasing domestic crude oil production – primarily from tight sands (colloquially called shales).

The chart below shows how these trends have evolved over time:

The international crude oil price first: note how the pale blue line starts to rise the week Biden won. This was expected because America needed higher prices as shale oils are expensive to extract.

Ever since the turn of the century, when new drilling and well completion techniques unlocked this bonanza in America, presidents have striven to ensure that the global oil price stays high enough to make such operations profitable.

Donald Trump perfected this black art by taking American oil production to record highs, and would have taken it further but for the horrific demand slump caused by the Wuhan virus pandemic.

In fact, as far back as in May 2021, Swarajya assessed that Biden would have to replicate Trump’s ideas if he wished to lift the American economy out of its rut:

“This transformational achievement effected by the Trump administration is, believe it or not, what Biden will need to work on, if he has any hope or intention of revving the American economy” (see detailed analysis here).

But that didn’t happen because of weak demand. As a result, drilling faltered and crude oil production stagnated. Note how the green rig count curve (a principal indicator of activity in the American upstream petroleum sector) is yet to rise to even half of what it was before the epidemic began; and how the purple oil production curve follows a flat, lowered trajectory following the slump in April 2020.

Meanwhile, though, international crude oil prices continued to rise, pushing up American retail gasoline prices in turn. Note how the orange gasoline price curve, which had remained under $2 per gallon for ages, started to rise immediately after the November 2020 elections.

This is the main reason behind the current, high inflation levels not seen in a generation: note how the thick, red inflation curve begins its alarming ascent with Biden’s entry. As the American Bureau of Labor Statistics notes in its latest report:

“The annual inflation rate in the US surged to 6.2% in October of 2021, the highest since November of 1990 and above forecasts of 5.8%. Upward pressure was broad-based, with energy costs recording the biggest gain (30% vs 24.8% in September), namely gasoline (49.6%)”.

That means prices started rising from the day Biden was elected, as did inflation, and international crude prices, because activity in the American oil patch didn’t take of as expected, due to a glut made worse by weak demand.

This is something Americans won’t stand for; the last time inflation rose like this in 1990, Bush Sr lost out on a second term, and a Republican presidential candidate hasn’t won California since.

With the shoe on the other foot, Biden is now presented with a perfect cleft-stick situation: he needed higher oil prices to boost domestic oil production from tight sands, which he got, but instead of higher domestic oil production, and resultant higher economic activity, he got hesitant oilmen unwilling to drill holes into the earth under the prevailing circumstances, and soaring inflation.

That leaves Biden in an unenviable position of somehow trying to reduce inflation while bringing the economy back on track. How does he do that?

His first real attempt, made six to eight months too late in this writer’s opinion, is to now try and reduce the international oil price. Biden’s plan is to put pressure on OPEC and Russia, the principal oil producers, by getting America and the other big consumers to release crude oil from their strategic petroleum reserves in an organised fashion.

It was discussed during the 15 November virtual summit between China and America. Since then, America has announced the release of 50 million barrels from its reserve. China is still mulling over the matter. India announced a release of five million barrels on 23 November.

And Japan’s Chief Cabinet Secretary, Hirokazu Matsuno, announced yesterday, 24 November, that they would be selling a part of their strategic reserves in conjunction with India and America.

"Stabilising the crude oil price is an important factor for realising economic recovery from the coronavirus pandemic," Matsuno said.

Will this work? On the face of it, five or 50 million barrels is a drop in the ocean. Even if the big consumers were to collectively offload, say, a few hundred million barrels of crude from their strategic reserves, it still only amounts to a few days worth of production globally.

The Saudis, the Russians and the rest of OPEC would be glad to play the waiting game, because the offloading of strategic petroleum reserves can’t last more than a week or a fortnight’s worth of crude. Once that arrow is shot, all these consumers would have to start re-stocking their reserves.

Who would supply that requirement? Here’s a thought: perhaps that oil might come from American shale plays at a cheaper rate (again, as Swarajya explained in May 2021, selling crude oil on a discount to China and India is something which Trump had already set in motion, to reduce America’s monstrous trade deficits). The giveaway is Japan’s reference to shifting its strategic reserves from heavy, sour crudes to lighter ones.

In all of this, there is also a separate strategic consideration which India has to bear in mind: if Biden needs China to put pressure on the oil producers by dumping strategic reserves on the market, and recommence the purchase of ‘shale’ oil from America, to reduce international oil prices, and to solve America’s inflation woes, Biden would have to sideline India’s security concerns somewhat.

China isn’t going to let Biden have the cake and eat it too, especially when Biden is in such a tight spot.

Besides, there is the bigger question of whether this move will work. It has too many moving parts, and presently seems like rather a gamble, even if international crude oil prices did reduce slightly in the past week (only to rise abruptly as this piece goes to the press!). If it works, that renewed sizzle in the American economy would be the payoff, globally and domestically.

If it doesn’t, though, Biden will need to find a new magic wand urgently, since it would mean that the old approach, of improving the American economy by increasing activity in its upstream petroleum sector doesn’t work anymore.

Worse, he would then also be stuck with inflation, a sluggish economy, an irate OPEC+, and an incensed electorate, with rather bleak prospects for his party in the mid-term elections less than a year away.

All data from the American Bureau of Labor Statistics, and the US Energy Information Administration

Venu Gopal Narayanan is an independent upstream petroleum consultant who focuses on energy, geopolitics, current affairs and electoral arithmetic. He tweets at @ideorogue.