World

Damascus Has Fallen: Seven Implications Of The House Of Assad Exiting Syria

Venu Gopal Narayanan

Dec 08, 2024, 06:57 PM | Updated Dec 13, 2024, 05:58 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Damascus, the historic capital city of Syria, fell to a Sunni Islamist force earlier today without a battle. While information is still sketchy, and largely unverified, the bald truth is that the Syrian Army let the Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), a Turkey-based, Turkey-aided group of ex-Al Qaeda members, to sweep from around Aleppo in the north, via Homs in the centre, to Damascus in the south, in just over a day.

That is a distance of over 300 kilometres. According to Russia Today, Syrian President Basher Al Assad has fled the country. Uncertainty looms large.

So, what are some of the implications of this staggering surge, launched immediately after Israel agreed to a ceasefire with Hamas and Lebanon?

One, half a century of rule by the House of Assad has come to an end. It was a brutal regime which conducted some of the worst excesses in modern history. The 1982 Hama massacre of Muslim Brotherhood rebels, when thousands were killed, and the use of chemical weapons on civilians, stand out for their particular notoriety.

Two, it means the end of the Ba’athist political experiment – a melange of socialism, pan-Arabism, secularism, liberalism and Islam – in the Middle East. At an elemental level, as practiced by the Assads in Syria, and Saddam Hussein in neighbouring Iraq, it was a convenient political tool to paper over ethnic divides, allow the elites to rule as they saw fit, for their benefit.

Three, the fall of Damascus marks the end of the overarching predominance of the small, Alawite community (a Shia-derivative sect) after a century of being at the helm. They were first co-opted and patronised by the French early last century, who even briefly carved out an Alawite State on the Syrian coast in 1919. The Alawites leveraged that first mover advantage to initially monopolize the bureaucratic structure, and then to seize political power.

But Syria is 75 per cent Sunni. Further, many Muslim schools do not consider Alawites as Muslims, not least because this sect employs wine in some of its rituals (a taboo in Islam), do not believe in daily prayers, recognize sacred texts other than the Quran, and venerate some Christian saints.

Consequently, the knives will be out for them now, particularly those who have lived in Damascus for generations, and hence lack the strength in numbers which their ilk on the coast can draw upon. And if things spin out of control, these Alawites could be the next set of refugees headed abroad (like the Kurds and Sunnis before them).

Four, according to Swarajya contributor Jai Menon, the failure of the Syrian Army to put up a fight means that the Iran-backed Shia Hezbollah, who were at the forefront of the civil war in Syria, and in fights against Israel, in Lebanon and elsewhere, are no longer a functional military force.

If so, then this diminishing of Hezbollah’s potency affects Iran’s strategic reach in the region. In its place, it is Turkey which has its shoulders up, since the Sunni HTS is of Ankara’s making. Iran will react, notwithstanding the pounding it received from Israel recently, but it is too premature to predict the ways and means of that.

By corollary, it is difficult to see Turkey successfully leveraging its hold over the HTS, partly because these holds are tenuous and will fray in exponential proportion to the pace at which the HTS fills the power vacuum in Syria.

Also, there are limits to how much Turkey can benefit because they are Turks, Arabs are Arabs, and that is a clear dividing line which history has never been able to erase.

Further, the native Kurdish population of Syria, now free of Alawite thraldom, would naturally seek out their Turkish brethren, and that is something Ankara cannot allow. So there are inherent contradictions which will come to the fore in time.

The fifth factor is Russia: Syria was its staunchest ally in the Middle East from the 1960s. It was Russia which kept the Assad regime in place for so long. Tartus port on Syria’s Mediterranean coast has hosted a major Russian naval base since the 1970s. But if press reports are to be believed, that Russian fleet has sailed out of Tartus.

Some say this is a deal with America, with Russia exiting Syria so that it can keep the Donbass in Ukraine.

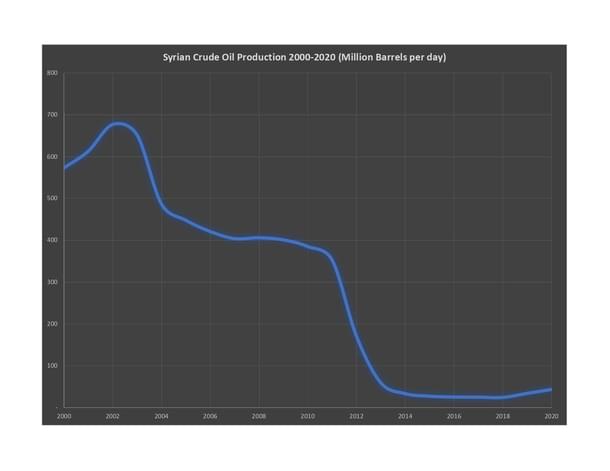

The sixth factor is crude oil: by the turn of this century, new Syrian discoveries in the east of the country, around Dier Es Zor near the Iraqi border, had boosted production to over half a million barrels of oil a day. This oil accounted for 15 per cent of Syrian exports, and 60 per cent of revenue. But with persistent insurrections and the civil war, many of the more promising hydrocarbon prospects could not be explored, nor could existing fields be developed. As a result, production slumped like a stone in 2012.

Thus, whoever fills the power vacuum in Damascus, will eye a revival of the Syrian oil industry, and if they don’t, there are any number of oil companies in the west who will nudge them into doing so, just like the companies which operate in Iraqi Kurdistan with no interference from, or control by, Baghdad.

And, finally, seven: the higher probability is that Syria is headed for a spell of Islamist rule. This is inevitable, since the Assad regime had kept the Mullahs in the background, and that in turn means, a period of severe puritanism and the re-institution of Sharia law, because, lest we forget, the HTS are merely Al Qaeda/ ISIS. It may well be that Damascus gets its first Emir in some centuries.

In conclusion, perhaps this is what the beginning of the end of the Colonial Era looks like, when maps and borders drawn long ago by Occidental colonialists for their benefit are savagely redrawn to reflect actual ground realities, and ersatz, imported secular ideologies are cast away and replaced by homespun ones.

Venu Gopal Narayanan is an independent upstream petroleum consultant who focuses on energy, geopolitics, current affairs and electoral arithmetic. He tweets at @ideorogue.