World

Is The Shine Of China's Ambitious Belt And Road Initiative Waning? Recent Summit's Leader Count Says So

Swarajya Staff

Oct 19, 2023, 06:21 PM | Updated 06:16 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

China this week (17-18 October) held the third edition of its ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) summit.

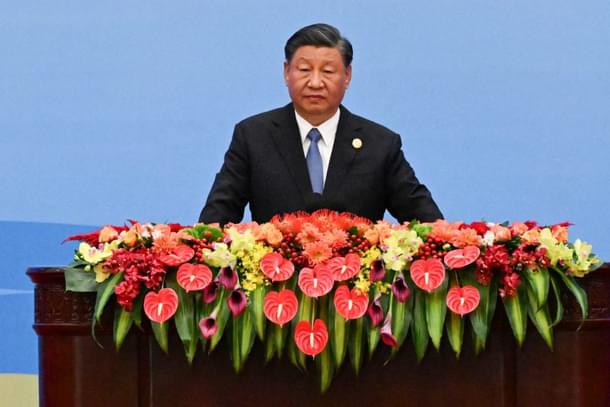

This is the 10th anniversary of the Chinese President Xi Jinping's pet project, BRI. Various world leaders are scheduled to attend the summit, Vladimir Putin being the most prominent leader.

However, it appears that the shine of China's most ambitious infrastructure project is waning.

In this year's summit, only 23 heads of state are attending, down 14 from last edition's (2019 BRI summit) 37 leaders, and four down the inaugural (2017 BRI summit) 27 leaders.

This comes just two months (September) after Italy, the only G-7 country which signed the BRI project in 2019, walked out from the project.

The Belt And Road Initiative (BRI) Project

The BRI project launched in 2013 plans to connect east and west overland across the Eurasian landmass and envisions three routes — from China to Europe via Central Asia, from China to the Persian Gulf and the Mediterranean via West Asia, and from China to South East Asia and South Asia.

The road, which plans to connect China with Asia, Africa and Europe through maritime routes by sea, also envisages three components: from China to South East Asia, on to South Asia, and through East Africa to the Mediterranean.

This ambitious infrastructure development project has seen China lending over $1 trillion to more than 100 countries, dwarfing Western investments in the developing world.

Predatory Nature Of BRI Loans And Debt-Trap Diplomacy

The BRI has encountered significant challenges.

Much of the Western world has voiced strong opposition to the project, citing concerns about its lack of transparency in loan disbursement and the predatory nature of the loans, which can lead to debt-trap diplomacy.

One notable instance occurred in 2017 when Sri Lanka struggled to meet its debt obligations for the Hambantota port project. In response, the Chinese authorities restructured the loan, ultimately securing a 99-year lease on the Hambantota port.

This problem extends beyond Sri Lanka; several BRI projects have failed to deliver the expected returns, leaving governments in substantial debt. Examples of such situations can be found not only in Sri Lanka but also in countries like Kenya, Pakistan, Tanzania, Argentina and Malaysia.

Furthermore, the BRI is perceived as a political tool used by China to provide advantages to Chinese companies while burdening participating nations with overwhelming financial obligations.

The project's sustainability and long-term implications have raised concerns in the international community.

How India Is Countering It?

India is not part of the project since the crown jewel of the BRI — China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) passes illegally through India's territory of Pakistan-occupied Kashmir (PoK).

India in a bid to counter the BRI announced a India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC), from the sidelines of G-20 Summit on 10 September.

Plans for the corridor, involves several countries including India, the UAE, Saudi Arabia, the European Union, France, Italy, Germany and the US.

It seeks to facilitate seamless trade and economic cooperation between India-Middle East and Europe, fostering socio-economic development and growth.

IMEC holds the potential to significantly boost trade volumes, creating new opportunities for commerce, investment, and economic integration.

Moreover, it can serve as a crucial bridge for trade between Asia and Europe, bypassing longer routes through traditional maritime corridors.

It promises regional cooperation and spur economic growth.

While the BRI remains a significant project, the reduced participation of world leaders raises questions about its trajectory. The recent exit of Italy, the sole G-7 country that had previously joined the project, reflects shifting sentiments towards the initiative.