World

Stagflation In America Part 2: Are The Solutions Beyond America’s Control?

Venu Gopal Narayanan

May 12, 2022, 04:14 PM | Updated 04:14 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Last week, Swarajya made two vital points with specific reference to a beleaguered American economy, and to the global economy in general.

One, that America was quite possibly headed into a period of stagflation, in which growth stagnated while inflation rose.

And, two, that monetary policy alone would be insufficient to remedy this situation.

These inferences were made based on a few interrelated observations, including an unexpected contraction of the American by 1.4 per cent in the last quarter, inflation rising to 8.5 per cent in March 2022 (the highest in decades), a rising yield on US bonds, which is, in turn, driving up mortgage and borrowing rates, somnolent demand, and a centennial disruption in the petroleum sector, caused by the West’s sanctioning of Russian energy exports over the Ukraine conflict.

In very broad terms, the Joe Biden administration’s response to this crisis, thus far, has been to increase the Federal Funds Rate (FFR) to one per cent by this week, thereby making investment in America slightly more attractive. This is linked to an expectation that, a rapid rise in American oil and gas production, primarily for export to Europe, would stimulate the economy, and permit America to profitably replace the oil and gas Europe presently buys in very large volumes from Russia.

The chances of this grand plan succeeding are low, and fraught with risks. (See here, here, here, here and here, for a five-part series on Biden’s Big Gamble)

America is finally beginning to wake up to these truths, even if its institutions are yet to. However, a remarkably candid essay last week by Neel Kashkari, President of the Federal Reserve of Minneapolis (sort of like a regional office of the Reserve Bank of India), marks an admission by a senior official of the American Treasury, that monetary policy may be insufficient to tackle the present economic crisis, because some of the root causes are outside America’s control.

These include supply chain disruptions on account of the ongoing epidemic lockdown in China, and the conflict in Ukraine. For example, Adidas, the global sportswear giant, has lowered its expectations for 2022 and cut its operating margin forecast.

Kashkari has not delved into the demand side of things, or commented on the severity or impact of commercial disruptions with Russia on account of the sanctions, but he does make a few points which merit analysis.

First, Kashkari thinks that one way out of stagflation is by targeting a ‘neutral’ FFR, which neither stimulates nor restrains the economy. In his opinion, that figure is 2 per cent.

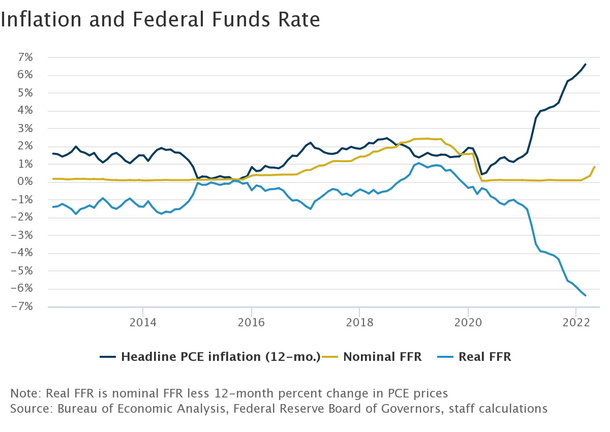

Second, he highlights a popular view amongst economists that the real FFR (nominal FFR minus inflation), which usually hovers between zero and minus two, is currently at -6.4 per cent. This sharp decline of real FFR to record levels is because of record inflation.

The Federal Reserve is unable to keep up since “inflation has climbed faster than we have raised rates”. As a result, analysts say that monetary policy hasn’t tightened, but loosened. ‘The Fed’ would need to raise rates by 6-7 per cent to catch up – which they can’t.

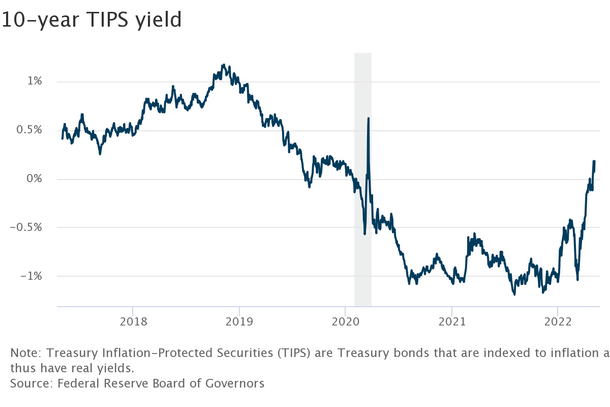

Third, Kashkari argues that a better metric for borrowing – the heart of all economic activity – is the long-term real yields on TIPS (Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities). These, he says, have edged back to slightly healthier pre-pandemic levels because the Federal Reserve started raising rates in the past few months.

Perhaps, but it still makes borrowing and mortgages more expensive, at a time when prices are soaring in America. Nonetheless, Kashkari avers that American monetary policy is on track.

But, fourth, he adds a caveat: inflation would ease only if the supply-linked issues do – the twin-effects of sanctioning Russia, and the ongoing lockdown in China. That’s where the big ‘if’ come in: if supply issues ease, then monetary policy will do its bit in taking America out of stagflation.

Unfortunately, by Kashkari’s own rueful admission, it doesn’t look like supply issues are going to be resolved any time soon. What does that mean?

Kashkari has an answer: “…then we will likely have to push long-term real rates to a contractionary stance to bring supply and demand into balance”. Translation: the solution to this sort of stagflation is a Fed-engineered recession.

The economics here is esoteric and hoary, but in effect, he says that demand should be curtailed, so that it can be brought better in line with supply limitations and labour shortages. This is rather like advising people to go on a fast every alternate day since there isn’t enough food available for all.

Sadly, this also where America is at, after a truly magnificent century of unparalleled prosperity and progress: they don’t have the tools to solve the problem, and they have no control over the root causes. All they can do is pray that American oilmen succeed in producing record volumes of oil and gas within the coming year, for sale to Europe.

A livid Lisa Abramowicz of Bloomberg didn’t mince her words when commenting on Kashkari’s essay: “Although the thoughts come from a Fed official who doesn’t vote on monetary policy this year, they are still alarming and should be taken seriously… they underscore the limits of the central bank’s ability to control key drivers of inflation right now, including a war that has upended oil supplies, causes prices for crude and energy overall to spike higher, and lockdowns in China”

“Fed members can't manufacture computer chips, control China's tolerance for Covid-19 cases or drill for oil”, she fumed; all they can do is “squelch demand”.

And yet, in the end, Kashkari can offer no better than a wait-and-watch salve, plus a rather bureaucratic recommendation, that economists and policy makers try and figure out what the best neutral FRR is, in the hope that American inflation can somehow be reduced soon to under 2 per cent.

The present economic crisis in America is of particular importance to Europe because it has been led into confrontation with Russia, on the promise that America would meet its energy and security needs. But can America do either, when its economic situation is presently so dire that senior policy figures are advocating a ‘squelching’ of demand as one possible solution that may or may not work?

At the same time, rising inflation and weakening demand are starting to hound Europe. Further, Europe has already killed its Russian market through sanctions. China is in a mess presently, both as a market and as a supplier. How bright will balance sheets seem if demand from the American market too, reduces further?

If this is how things are presently, then Americans and Europeans, along with large parts of the rest of the world, are going to start asking Biden in increasingly agitated tones, whether it was in fact worth it to trigger a crisis in Ukraine, when there was already a bigger crisis simmering at home?

Also Read: Stagflation In America: Yes, It's As Bad As It Sounds

Venu Gopal Narayanan is an independent upstream petroleum consultant who focuses on energy, geopolitics, current affairs and electoral arithmetic. He tweets at @ideorogue.