World

The Battles Of Monte Cassino: A 75th Anniversary Tribute To The Indian Army

Venu Gopal Narayanan

May 22, 2019, 02:41 PM | Updated 02:41 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

The Benedictine Abbey of Monte Cassino sits atop a steep hill in southern Italy, about halfway between Rome and Naples. Consecrated in the sixth century, it remained a refuge for pious contemplation until the Saracens burnt it to the ground in the ninth century. It was rebuilt in the twelfth century and remained intact, and in use, until the Second World War, when in 1944, it became the site of one of the bloodiest battles ever fought.

As the opening act of their Italian campaign, and as the first step in a march on Berlin, the Allies captured the island of Sicily in August 1943. Next was the amphibious landing at Salerno, just south of Naples. Then they began the long, arduous fight up the slender peninsula. The Germans, under Field Marshal Kesselring, were not in a particularly welcoming mood, and made the Allies pay heavily for every inch of advance. The Allied blood spilt belonged to many races – American, Canadian, British, New Zealander, South African, Moroccan, Polish, French, Algerian, and, importantly, Indian.

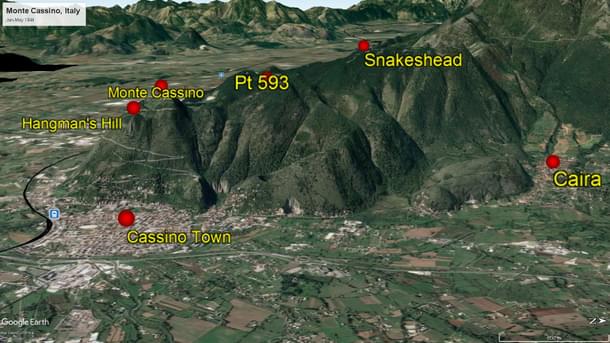

By January 1944, the German defensive positions had settled at Cassino town, at the base of a hill, forming what was known as the Gustav Line. The strategic importance of this pretty town was known to all – it was the only gap in the Apennine Range, which runs along the length of Italy. If Cassino fell, valleys leading to Rome would fall into Allied hands, and with that, the Germans would lose Southern Italy. Next stop would be the Alps, beyond which lay ‘Fatherland’ Germany. So, the stakes were extremely high.

The first battle in January 1944 went badly for the Allies; so badly in fact, that American General Mark Clark was hauled up by the US House of Representatives after the war. They actually called it ‘one of the most colossal blunders of the Second World War…’ A near-frontal assault by the US II Corps, the British X Corps, and the French, was so violently repulsed by the Germans that many of the Allied formations were rendered unfit for further action. That caused a pause in the conflict, and a gap in the line – a vital gap, which was filled by the Second New Zealand division (2 NZ), and the famous Red Eagles from India.

The Fourth Indian Infantry division (4 Div) was the elite, the crème de la crème, having earned the respect of no less than German legend Irwin Rommel, in North Africa. It was the senior most Allied infantry formation of the Second World War, going into action in 1940 itself. The Red Eagles knew how to win battles, in style. No wonder ‘The Desert Fox’, as Rommel was known, called 4 Div the finest fighting outfit he had ever seen. And now, in the cold winter of Italy, the famous Fourth would once again play its part, in the cause of freedom and liberty.

Unfortunately, the second battle got off to a disastrous start. Thanks to deplorably shoddy coordination, someone very high up on the ladder decided to bomb the monastery without informing the assault forces. As a result, 4 Div were rushed into action without adequate preparation. The US Air Force strike was devastating, but 4 Div weren’t yet in position to capitalise on this. Worse, the bombings turned the monastery into rubble, which provided excellent cover to the defending Germans. And to top it all, 2 NZ, who were still just moving into position, were asked to cross a river and take Cassino railway station without tank or artillery support.

4 Div, based to the north around the village of Ciara, were still struggling to establish themselves, on a bald, open feature called Snakeshead Ridge, when the orders to attack went out. They did their best to comply. The Sussex regiment, the Gurkhas, and the Rajputana Rifles, put in a series of valiant attacks across 16 to 18 February. But the Germans were too well entrenched at a vital rise called point 593, to be dislodged. Hundreds of our men died. A young officer recalls how he sobbed in frustration, just 70 yards short of point 593, when a hail of machine gun fire cut his men to bits. So close. So damn close.

On 19 February, General Freyburg, commanding 4 Div and 2 NZ, called off the battle and pulled his men back into the plains. There was simply no point in proceeding with the plans. Then a lull followed for a month, filled with sniping and penny-packet actions, as the two divisions were bolstered by a third – the British 78th (78 Div). And all the while, the Germans continued to reinforce their troops atop Monte Cassino, including with the crack First Parachute Division.

The third battle began in mid-March. No one liked the plan – a near-suicidal full-frontal assault up steep slopes with little cover, not least the Allied Generals. But it had to be done, because Monte Cassino stood like a rock, blocking the road to Rome.

Once again, it was 4 Div to the fore, and this time, our Gurkhas managed to take Hangman’s Hill at an immensely high cost. They were now barely a few hundred yards from the monastery, and ready to make the final attack. Tanks were slowly brought up winding mountain tracks. Supplying them was a murderous task because there was no cover. Every day, more of our brave men died. Still they held on.

That was when the Germans did the unthinkable – they counter-attacked! In a fierce display of military brilliance, they pushed our forces back, and in a single afternoon, knocked out all the tanks. That left the Gurkhas holding on to Hangman’s Hill, with no supplies, no chance of making the final assault, and no way out. It was much the same story down below, in the plains around Cassino town: the Germans resolutely held on, and in a series of deadly house-to-house actions, punched 78 Div back beyond the town limits.

Once again, the battle was lost, and once again, General Freyberg was forced to recall his troops. They took three full days to extricate the Gurkhas from Hangman’s Hill. The casualties were staggering – 4 Div lost 3,000 men. 2 NZ and 78 Div too, were beyond exhaustion and in dire need to repair. So again, a vexing, abeyant lull ensued, while these troops were taken off the line. The Red Eagles had soared magnificently, but this time, the odds had been simply too great for the Famous Fourth to blow the victory bugle – as they had done so often in the past.

After this, it was amply clear to planners that Monte Cassino wasn’t going to fall until the German lines of supply were cut. For that, they needed more, fresh troops. So, a larger plan was drawn up for a fourth battle. It introduced another famous Indian formation to the defenders of the abbey – the Eighth Indian Infantry Division (8 Div).

Men of 8 Div were known as the ‘Clovers’, because of the three-flower insignia on their shoulder patch. Thus far, they had had a restless war, ranging from the occupation of Iran, to adventures in Syria, a hammering courtesy Rommel in North Africa, and a tough slog up the Italian peninsula. The men were from everywhere – Bengal, Maharashtra, Rajasthan, Balochistan, and the Punjab, amongst others. They were almost always in action, to the extent that with mordant, sardonic military humour, they adopted the phrase ‘One more river!’ as the divisional motto. You can only salute such men who laugh at death.

The fourth battle began on 11 May 1944. 8 Div’s first objective was the crossing of the Gari River, to the south of Cassino. A thousand years earlier, this area had been under the control of Arabs, who ravaged Central Italy until a Pope put them down. Now, a fresh generation of men from the east, of 8 Div, commenced a considerably fiercer assault, ironically in part to free a Pope from Nazi thrall.

8 Div established and held their bridgeheads against brutal fire, as tanks raced across the river to engage in armoured contest. It was the most crucial part of this fourth battle, and 8 Div did their duty in exemplary fashion. It is in this action, that 19-year old Sepoy Kamal Ram of 8 Punjab, and hailing from Rajasthan, was awarded the Victoria Cross for his valour. There were many, many others, and some day, the divisional records shall be studied in detail, so that their epic story is told in fuller measure.

To the north, the Poles, who had replaced 4 Div, took Snakeshead Ridge with the aid of well-coordinated artillery and air support. Everything that 4 Div lacked was now in place, and a majestic Allied victory was finally wrought. Monte Cassino was theirs. The road to Rome was open.

Of course, the war went on for another year. There were more sacrifices, some known, most untold. In all of that, the fierce battles of Monte Cassino mark a turning point in the European theatre of war, and the contributions of 4 Div and 8 Div within. Indeed, some say that the requisite confidence to launch the Allied invasion of Normandy in June 1944, was provided by the success of the Italian campaign.

Today though, Monte Cassino sits in tranquil beauty, with the marks of war long gone. The abbey has been rebuilt, and the monks are back in habit. Visitors trudge up the paths to visit the war cemetery near the abbey’s base. Some, seeking to retrace the exploits of 4 Div, make the trek from Ciara.

But the best view is from the railway tracks, when at a bend, you can make out Hangman’s Hill, Snakeshead Ridge, and, if the sky is clear, point 593. Then, the best you can do is raise a toast to those brave warriors of India, who travelled so far, and fought so hard, to rid the world of dangers. We must never forget their sacrifices. We are what we are because of them.

Venu Gopal Narayanan is an independent upstream petroleum consultant who focuses on energy, geopolitics, current affairs and electoral arithmetic. He tweets at @ideorogue.