Commentary

Deciphering the Strategic Logic of Electoral Alliances

Prashant Kulkarni

Jun 22, 2013, 12:04 AM | Updated Apr 29, 2016, 01:30 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

The unpredictability of the voter behaviour makes elections fascinating. The village or the town squares or roadside tea shops or even pans shops and these days social media become centers for ‘gyan’ for understanding dynamics for voter behavior. Discussions in the academic campuses remind of the romantic evocations of the proletarian revolutions that always seemed just over the corner and might enter the campus any moment (they never entered- that is the different matter).

Theories float in abundance. Given the tenor and tone of these discussions, not without reason, separating hype from reality is arduous. In recent years, the absence of pan-Indian parties with the probable exception of the Congress, often result in fractured verdicts at the national level. Moreover, Lok Sabha elections become a macrocosm of micro election configurations at the state level.

Personality factor, caste combination, track record, besides the incumbency issues end up determining state verdicts. With political parties entrenched strongly in the states, state elections are often bipolar. With new party penetration in states increasingly difficult, parties find difficult to move beyond their traditional base.

The inability of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) to penetrate in the South (barring Karnataka) or the East illustrates this. Exceptions are often the breakaway factions of a national or even an existing regional party. Barring Janata Party (JP) in 1977 which captured around 41%l of the vote (it was essentially a coalition of four groups on single point platform of opposing Emergency), no non Congress party could establish itself as a pan Indian party. Even giants like B.R. Ambedkar or J.B. Kriplani failed. Post JP split of 1979, BJP comes closest securing more than 25% of the votes both in 1998 and 1999 before experiencing a decline since 2004.

Thus, a perceived need for both the Congress and the BJP (at least post 1998) to strike the pre-poll alliances and post poll power sharing arrangements to remain in contention. While BJP and Congress have successfully managed alliances, formations headed by non BJP, non Congress actors, tend to be unstable (observe 1989, 1990, 1996, 1997).

While both Rahul Gandhi and Narendra Modi seem to breaking this mould, the outcome of the attempted redrawing the role of regional alliance partners in future power sharing arrangements remains untested. Yet it is worth pondering over the strategic logic of alliances. The current paper, borrowing from management literature dissects the logic of political alliances and its utility in the current context.

Strategic Logic of Alliances

Sumantra Ghoshal et al in the celebrated book ‘Managing Radical Change’ make certain observations about the strategic raison d’être of acquisitions. The observations arise of the experience of Leif Johansson (of Electrolux Home Appliances and later CEO of Volvo). Johansson posits non-linearity between market share and profitability.

Both small and very large players find viable profitable positions in niches for the former and across multiple segments for latter. For those mid-sized companies populating between these two groups, there lies a large ‘no profit’ land’ generating below average industry returns. These firms neither can play the niche game nor compete at the highest level (Figure I)

Figure I- Understanding Firm growth

Source: Adapted from Sumantra Ghoshal, Gita Piramal, Christopher Bartlett, “Managing Radical Change: What Indian Companies Must Do to Become World Class”, Penguin Books India, 2000

Analogous to this, every political party too, goes through this cycle. Regional or sub regional parties with the roots in a particular state or captive vote bank occupy Zone A. National parties particularly the Congress pre 1989 can be said to occupy Zone C. BJP at least post 2004 seems to have been stuck in Zone B The current analysis looks at BJP’s both past and present experiences to move from Zone A to Zone C without getting stuck in ‘no-profit land’. The construction of National Democratic Alliance (NDA) can be cited as part of this logic as we will see shortly.

Firms adopting organic growth model face long periods of below industry average Return on Investment (RoI) that dampen shareholder expectations. Similarly, parties face long haul in organic penetration of non strongholds with an already existing entrenched political environment.

Frustration and demotivation among both cadre and committed voters results when party electoral performance is not in alignment with the prescription of high expectations the party might have generated.

Pre-1989, BJP and its predecessor Bharatiya Jan Sangh (BJS) were marginal players confined to a few pockets in the Hindi belt. The spectacular increase in seats from 2 in 1984 to 85 in 1989 to 119 in 1991 made BJP a national player for the first time. Cadre expectations naturally heightened. Though BJP termed it ‘splendid isolation’, the collapse of the 13 day government in 1996 revealed the limitations of organic growth as also the inability to stitch alliances at regional level.

Fear of alienation of Muslim votes and lack of regional base deterred regional parties in tying up with the BJP. Barring Karnataka to some extent, BJP was unable to leverage voter apathy towards Narasimha Rao (PVNR) regime and the projection of AB Vajpayee (ABV) as the prime ministerial candidate outside its traditional strongholds.

Power could come only through alliances at the state level or it faced a long haul in opposition till it breaks into non-Hindi belt states. The answer lie in building alliances and the fact they built and sustained it through 1998-2004 stands testament to a jump from Zone B to Zone C in short period of time.

Motivations for Alliance Partners

Yet, the above analysis misses out the motivations for the prospective alliance partners. Many of these parties shed inhibitions to a party they termed untouchable only a year or so before. The answer, which partly explains the current political context too, lie in certain imponderables, the regional parties face. It would we worth borrowing from management literature again.

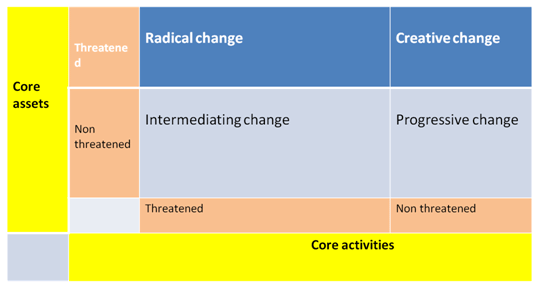

Industries evolve along four distinct trajectories. These trajectories- radical, progressive, creative and intermediating delineate the boundaries on what generates profits in business and are the outcome of the relationship between the core assets of the firm and core activities the firm undertakes.

Core activities historically sustain the firm’s profits while the core assets comprise resources like knowledge, physical capital, intellectual property, brand etc that make the organization unique. The firm may face threats to either of its core activities or assets or both (Figure II) and its response to these threats determines the firm’s future.

Figure II- Industry Trajectories

Source: Anita MacGahan, “How Industries Evolve”, Harvard Business Review, October 2004

Political parties too, evolve similarly and face similar threats. Threats include ‘hostile’ government in power, succession battles within the party, cadre disillusionment, breakaway factions etc. Core activities encompass all those activities than enables the party to function as an effective ruling or opposition party. Core assets include the leadership, dedicated cadre, dedicated vote bank, ideological underpinnings etc.

When NDA was formed in 1998, its constituents were Akali Dal, Shiv Sena, Samata Party, Biju Janata Dal, Trinamool Congress, AIADMK, couple of other regional TN parties, Lok Shakti etc. The rest of the crowd barring Telugu Desam (TDP) (TDP joined during vote of confidence 1998) joined later in 1999 or after that. Akali Dal was historically rooted in anti-Congressism and Sikh politics, Shiv Sena derived from its identity politics in Maharashtra. Samata Party, breakaway JD faction led by Nitish Kumar and George Fernandes, came a cropper in 1995 Bihar assembly elections.

Political party’s core assets like dedicated cadre base or personality of the leader were in premium (Nitish was neither a familiar face nor his caste Kurmis numerically dominant). An existential threat forced them to throw lot with the BJP in late 1995. Biju Janata Dal (BJD) formed out of remnants of JD in Orissa post Biju Patnaik’s death. Navin Patnaik’s untested image (forced into politics after his father’s death), increasing BJP vote base particularly in Western Orissa challenging the traditional JD vote bank necessitated an alliance with BJP to take on the ruling Congress.

Mamata Banerjee’s was fighting a lone battle against the Left with very little support from the Congress high command. To retain relevance and motivate grassroots cadre, she needed to break away from the Congress yet needing support at the Centre to combat Left – threat to her core activities at the ground level. Ramakrishna Hegde, post expulsion by Deve Gowda, needed to maintain his relevance (Respect alone need not make politician electorally relevant), the tie-up with the BJP was natural.

Chandrababu Naidu needed to establish an identity independent of NTR and the party performance in 1996 and 1998 elections was not encouraging (though TDP played larger than life role in United Front formation in 1996). Hence, the decision to support ABV in 1998 vote of confidence (It is different matter that BJP cannibalized itself in Andhra to allow Chandrababu to flourish in that period, the price of which it is still paying today).

DMK sweep in 1996 elections and facing trial in cases of alleged corruption, Jayalalitha needed support and chose to ride on ABV wave than allying with perceivably sinking Congress. Thus circumstances that threatened assets or activities of political parties and the need to overcome those threats resulted in the formation of NDA. Thus is the product of unusual times, unusual churnings that shake up the Indian political system at times.

Conclusive Remarks

Currently, BJP is perhaps back to early stages of Zone B. To reenter Zone C, either alliances or a strong voter swing needs to generate the push. Jayalalitha, Navin Patnaik, Mamta Banerjee all currently in power, are unlikely to share their political space with others. Instability within parties is not apparent with probable exceptions like Shiv Sena (BJP ally) and DMK.

Nitish Kumar perceives, being unattached, is as an asset to be encashed post elections. His choice to sticking to NDA (unlike Naveen Patnaik) was linked to his survival, while the near majority in 2010 elections released him from such compulsions.

Other parties are unlikely to contribute significantly to the kitty (e.g. AGP precarious due to demographic changes and factional fights, Lok Dal in Haryana in trouble with its leader convicted in corruption case)

Prima facie, vulnerability in terms of assets or activities to the regional players is not apparent and neither is tie-up with BJP facilitating consolidation of their votes. In the absence of conditions that existed in 1998-99, the dream of grand revitalized NDA may prove to be a non-starter. Alternatives need to be explored.

Voter emotions, particularly on a powerful issue or a powerful slogan can swing an election decisively. Indira Gandhi’s Garibi Hatao (culmination of her inner party victory over the Syndicate as also shaking off the dependency of the Communists) or Rajiv Gandhi gaining sympathy votes following his mother’s assassination in 1984 are good examples. Incidentally, BJP’s first attempt to move from a marginal player to national level was through Ayodhya issue (first challenge to Nehruvian model of secularism) was an example of emotional issues as a factor in voting decisions.

It was a risk, but probably fell short of the task leading to below than hyped returns of 1996 forcing the BJP to take the route of alliances. There is definitely risk of polarization, yet as we find polarization may result in decisive leaders than fence sitters.

Both Regan and Thatcher were great polarizers and yet go down in history as among the successful leaders in their country’s history. Yet, it may not deliver sufficient seats. In 1991, except for UP and Gujarat, BJP could not translate the groundswell into votes in states like Karnataka (notwithstanding the sympathy wave post Rajiv assassination) and West Bengal (obtained 11% votes but not translated into seats). On the contrary, they lost quite bit of ground in Madhya Pradesh.

A complacent and passive opposition will not benefit from anti-incumbency nor will attract alliance partners. Harnessing issues at the ground level to generate a decisive swing is pre-requisite to bid for power at the centre. In 1996, situation similar to the current one, BJP inability to leverage neither ABV personality factor nor Hindutva resulted in ending up at 161 seats.

Besides, The Samajwadi Party (SP) – Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) split accounted for UP gains, Rajasthan was a stalemate, Gujarat bogged down by the local dissidence, Karnataka squeezed between ruling JD and the Congress, and ended up as also ran in Kerala, Bengal, Orissa, Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu (KBOAT) States. BJP’s belief in being passive recipient of negative vote against the ruling party resulted in erosion of seats as also vote share in 2009.

While mere anti-incumbency or alliances to swing the game for the BJP would be too much to expect, a massive jump to 200+ seats that can occur only through an electoral wave resulting in the vote multiplier.

Whether, track record of good governance or promises of an aspirational India can result into powerful voter emotions to swing out the existing government remains to be seen. Yet in politics, risks have to be taken. Does the party today has in it to go all out and create that swing or even do conditions exist for the swing to happen? Time will answer.

References

- Sumantra Ghoshal, Gita Piramal, Christopher Bartlett, “Managing Radical Change: What Indian Companies Must Do to Become World Class”, Penguin Books India, 2000

- Anita M. MacGahan, “How Industries Change”, Harvard Business Review October 2004

- www.indiavotes.in (For poll percentages)

Prashant Kulkarni teaches economics, a digital economy and globalization at a leading B-School. His area of interest lies in dissecting resource contestations and human behavior at the intersections of digitization, urbanization and globalization.