Defence

How India Reacted To The Deployment Of US Aircraft Carrier 'Enterprise' In The Bay Of Bengal During 1971 War

Swarajya Staff

Dec 03, 2020, 03:28 PM | Updated 03:28 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

A week after hostilities broke out on the western front with Pakistan on this day in 1971, Indian forces were quickly closing in on Dhaka. With the Pakistani war machine in the east damaged and out of action by now, the only resistance to the Indian forces moving towards Dhaka was coming from the many rivers in East Pakistan, which made the terrain very difficult to operate through and unsuitable for manoeuvre.

As Indian forces marched forward, anxiety grew in Washington. Fearing that Indira Gandhi will turn on West Pakistan after taking East, and unwilling to be seen as letting an ally be defeated by Soviet-backed India, then US Secretary Of State Henry Kissinger made a case for US intervention in the conflict.

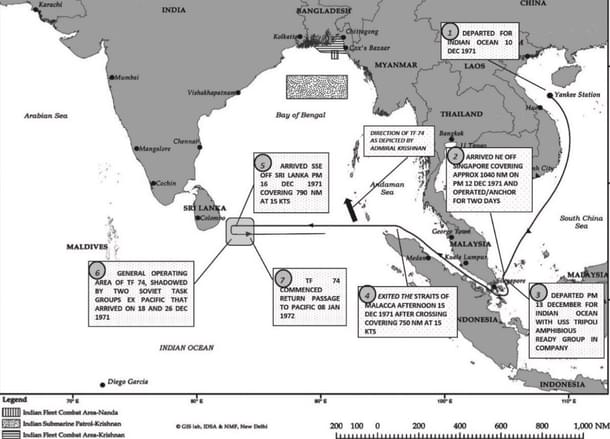

As Admiral Elmo Zumwalt writes in his memoir On Watch, a Presidential order on 10 December created Task Group 74, which was to be deployed in the Bay of Bengal.

Led by the the US Navy’s largest aircraft carrier, the nuclear-powered USS Enterprise, the Task Group consisted of amphibious assault ship USS Tripoli with a Marine battalion and assault helicopters; the three guided missile warships USS King, USS Decatur and USS Parsons; four gun destroyers USS Bausell, USS Orleck, USS McKean and USS Anderson; one ammo ship USS Haleakala.

On 12 December, as Hilli, Mymensingh, Kushtia and Noakhali were being liberated by the Indian Army, US Navy’s Task Group 74 was ordered through the Malacca Straits into the Indian Ocean. The order was rescinded an hour later, only to be reissued with the instruction that “as much of the passage through the Straits as possible be in daylight, ie in full view of the world,” Admiral Zumwalt, who was serving as the Chief of Naval Operations of the US Navy, writes in his memoir.

Here’s how US’s decision to send a Naval Task Group to the Bay of Bengal during the 1971 war was seen in India:

Peter Sinai, Director (Bangladesh) in the Ministry of External Affairs during the 1971 war with Pakistan, recalls:

“On 14th December, the Political Counsellor in the US Embassy in Delhi sought an urgent meeting in MEA with me and handed over a telex copy of US Defence Secretary Melvyn Laird's statement that the Carrier Group Enterprise had been ordered to proceed to the Bay of Bengal "for evacuation and other contingencies". I pointed out that all US nationals desiring evacuation had already been evacuated and demanded to know for whom "evacuation" was intended and what the "other contingencies" might be. Mr Irwin said that his instructions were only to deliver the Defence Secretary's statement.

"I rushed the message to Mr DP Dhar, who said he would inform the PM and that I should meanwhile take a copy of it to NHQ. I took the message to the South Block War Room. The immediate reaction of the naval personnel there was one of incredulity and concern. Awareness that the range of the aircraft on the Enterprise posed a threat to VIKRANT and other naval vessels operating off Chittagong well before they could be in any position to retaliate was the main expression of that concern".

Captain (later Vice Admiral) MK Roy, Director of Naval Intelligence in 1971, in his book “War in the Indian Ocean”, writes:

“The composition of the US Task Force as seen from satellite photographs included the nuclear-propelled aircraft carrier Enterprise, the amphibious assault ship, TRIPOLI with helicopters, and an escort of three guided missile ships, four destroyers, nuclear attack submarines and tankers. Prime Minister Gandhi arrived early in the Naval War Room and queried Admiral Nanda as to the implications of this US move. I was asked to give a quick appreciation of the capabilities of the US Task Force. I concluded by stating that it could be any of the undermentioned operations:

(a) Intervene by invitation as the Enterprise could wrest aerial supremacy over the skies of East Pakistan. The marines could then be airlifted ashore by helicopters to assist the Pakistan Army. This was however thought to be impractical as the Vietnam war was not going in favour of the US.

(b) Interpose between the coastline and the Indian blockading forces thus breaking the ring round the East Pakistan coast particularly involving the ports of Chittagong and Chalna.

(c) The US Task Force possessed the vertical lift capacity to evacuate at least one Pakistani division with their personal arms to ships in international waters. It would then be possible to transport them to West Pakistan by sea to bolster their Army facing the impending attack by India after the surrender in East Pakistan. Both Pakistan and US were aware of the restrictions imposed on civilian traffic by the Indian Railways in order to expeditiously move Indian divisions from the Eastern to the Western theatre of operations”.

In his book ‘No Way But Surrender’, a memoir of the 1971 war, Vice Admiral N. Krishnan, who was the Flag Officer Commanding-in-Chief of the Eastern Command of the Indian Navy, states:

“At about 5.30 PM on the eighth day of the war, Friday, 10 December, we intercepted a signal to the effect that the US Navy was sending ships into the Bay of Bengal, for possible withdrawal of the Pakistani Army.

“I also spoke to Admiral Nanda regarding the 7th Fleet but he had heard no more than what was in the signal. We ended our conversation on the note that we should not be surprised by anything that happened from now onwards.

“None of us ever fell for the gimmick that the Fleet's object was to evacuate a handful of American subjects from Dacca. You do not require an elephant gun to shoot at a flea. Obviously, her primary intention was to frighten us into withdrawing our forces from the operational area and let the escape ships break out. Suppose we didn't scare that easily and persisted in our stranglehold on Bangladesh?”

“Evacuation of any but a handful of troops was a possibility, using helicopters. Clearly the use of heavier and very powerful aircraft was quite out of the question as, however thorough the temporary repairs, the runways of both Chittagong and Dacca had taken considerable beating.”

The offensive capabilities of the Fleet, therefore, consisted of:

(i) Landing up to a marine battalion as an assault group using helicopters

(ii) Using the Enterprise aircraft for ground support role

(iii) Providing close support against aircraft attacking their fleet and

(iv) Surface and aerial attack on Indian warships.

“We did not know if the marine battalion was carried on board the TRIPOLI at the time but even assuming that they were, how were they going to land them ashore except by helicopters. It was quite obvious that manpowerwise, landing some 2,000-odd persons was not going to materially alter the land battle in which some 93,000 soldiers were gasping for breath!

“It was unthinkable that they would commit their aircraft on a ground support role against our army or air force or want only attack our naval forces at sea. If they did, it would possibly mean war between the United States and India and, as I said to my colleagues in the Maritime Operations Room, "that might mean the end of the world or the Americans would find in us a Vietnam to end all Vietnams.

“To my way of thinking, the most effective method of helping the Pakistanis would be to close Chittagong within range of their air power, put up a formidable air umbrella over the merchant ships awaiting escape and actually provide air escort for them till they reached the waiting fleet. They knew that our tiny force of aircraft from VIKRANT could never hope to challenge the air cover and we could at best watch the trapped animals getting away from our clutches.

“Summing up the appreciation, we came to the following conclusions:

(i) A critical point was being reached in the war and the Pakistanis were desperate and would try to break out at the earliest opportunity.

(ii) For this purpose, they had at least five merchant ships ready and camouflaged in Chittagong. They had made desperate attempts to make the runway at Chittagong sufficiently serviceable to take light aircraft and helicopters.

(iii) The safe arrival of the convoy RK 623 would be the starting point of putting their “Scorched Earth Plan” into action.

(iv) The removal of VIKRANT from the scene of operations would ease the way to a break out. The Pakistanis must have hoped that we would withdraw VIKRANT to “get out of the way of the Seventh Fleet”.

(v) A break-out of ships could be facilitated by the Seventh Fleet providing an impregnable and continuous air umbrella till they joined the surface forces of the Seventh Fleet.

“Having thought out the various possibilities, it was necessary to plan out our line of action. Clearly, everything turned on the merchant ships assembled in Chittagong for the actual troop carrying. Not an instant must be lost in destroying or so heavily damaging them as to make them totally immobile. Time was running out.

“Having spent the whole forenoon of 11 December on the above thoughts and a series of discussions with Admiral Nanda as well as my army colleague Jagjit Aurora, I signalled the Fleet at 1.15 PM as follows:

(a) Appreciate enemy with senior officers including FOCEF planning major breakout and will try to get away by hugging the coast. Senior officers may try to escape by air. Approaches to harbour likely to be mined. (b) Your mission: (i) Put Chittagong airport out of commission; (ii) Attack ships in harbour by air and surface units if they break out. (c) This is undoubtedly the most important mission of the war in the East. The enemy ships must, I repeat, must, be destroyed. Good Luck.

“In addition to the air strikes, we also decided to carry out a surface bombardment of Cox's Bazar to obviate even a marginal use of the aerodrome there by any type of aircraft.

“There could now be no question whatsoever of evacuation of the West Pakistani Army by sea and General Manekshaw's warning:

“Nobody can reach you from the sea. Chittagong, Chalna, Khulna, Mongla are all totally blocked,” was entirely meaningful. To make absolutely sure, I thought of a deception and sent this signal to Naval Headquarters.

“I Submit that should government decide to prevent Seventh Fleet approaching to Chittagong in order to buy time suggest announce that mining of approaches has been carried out. For favour of consideration”.

Lieutenant General JFR Jacob, who was Chief of Staff, Eastern Army HQ, recalls:

“Admiral Krishnan was very worried. He rang me up on 14 December and asked “What is this about”? I told him “I am already talking to Lt Gen Niazi about his surrender. If on the 14th, the Americans are in the Straits of Malacca and the cease fire is to come on the 15th, how can the American naval task group move up to the North Bay of Bengal in time to give then any help? Why then are you worried”? He seemed to be obsessed with the Enterprise Task Group. I don't know why”.

In his book We Dared, Admiral SN Kohli states:

“On one of my visits to the Soviet Union, Admiral Gorshkov mentioned to me that he had a “brigada” of submarines following the Enterprise squadron. It is now known that Gorshkov surfaced all the Soviet nuclear submarines in the Indian Ocean when the US satellite was overhead the 7th Fleets incursion into the Bay of Bengal”.

Prof PN Dhar, the Secretary to the Prime Minister in 1971, recalls:

“The impression that the Enterprise was a response to the Soviet move to help us is just not correct. The Enterprise group was followed by the Soviets and not the other way round. The Soviets did tell us where the Enterprise was, they had their own way of checking on Enterprise’s progress and they did keep us informed about that. And that is why the American Embassy here was a little surprised at the nonchalant attitude of the Government of India”.