Economy

So What is GST, and What Are Its Benefits?

Seetha

Dec 17, 2014, 12:07 PM | Updated Feb 10, 2016, 05:19 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

The Goods & Services Tax (GST) has been debated in India for nearly a decade. But now, finally, it looks like it will be a reality soon. So what is GST, and what are its benefits? Swarajya offers a primer

Finance Minister Arun Jaitley held discussions with state finance ministers over the last two days in a determined bid to seal a deal on goods & services tax (GST) that his ministry officials said is as close as it has ever been. The Modi government wants to ensure that this key element of its economic reforms agenda can be put in place by April 1, 2016, as part of efforts to speed up growth.

Finance Minister Arun Jaitley, committing to push the GDP growth rate to 6-6.5 per cent in the 2015-16 financial year, on Friday said the government was working overtime to push reforms, especially in sectors like insurance, coal and the Goods and Services Tax (GST).

“We are working overtime on reforms… Insurance Bill will be taken up next week,” Jaitley said while speaking at a programme organised by the India Today Group-owned television channel Aaj Tak.

The Finance Minister further said that he sat late on Thursday evening with state FMs to sort out the issues hampering the rollout of the long-pending GST. “I will try to introduce the Constitution Amendment Bill for GST in the current session of Parliament so that it could be discussed and considered in the next session,” Jaitley said.

So what is this all-important GST?

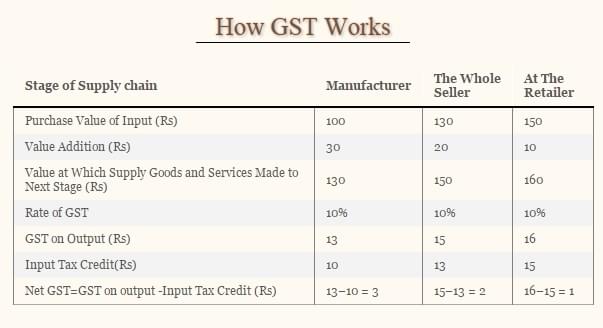

It is a single, comprehensive value-added tax on goods and services that is levied at every stage of a transaction. The person paying the tax can offset it as an input cost. Thus, tax is levied only on the value added during a particular stage of transaction.

It really shifts the burden of tax to the point of final consumption. But the tax burden on the final consumer will be less than it is now because taxes paid earlier have been set off.

Understanding GST

Why a GST

It will do away with cascading of taxes or the tax-on-tax phenomenon where the tax paid at one stage gets added on to the price of a good on which tax is levied at the next stage. So it will reduce the tax burden on goods and services for the final consumer.

GST will also end the multiplicity of taxes that make compliance with, and administration of, indirect taxes a nightmare. It will improve indirect tax collections by broadening the tax base, making evasion less attractive (you can get tax credit only if you have paid tax earlier).

Above all, it will create a common market in India, since the rate will be uniform across the country and taxes paid in one state can be offset for transactions done in another.

But wasn’t VAT supposed to do all this?

Yes, and it did, to an extent. Sales tax, which preceded VAT, was a cascading type of tax. Besides, states levied several other taxes, all of which not only made things difficult for manufacturers and traders but also increased prices. With VAT being introduced in 2005, people at various points of a transaction chain could set off the taxes they paid on previous transactions. Most of the other taxes were also subsumed into VAT.

However, VAT has some shortcomings. It does not include all taxes/levies at the central and state level, which it should have. What’s more, some of these taxes cannot be set off as input tax credit. Also, VAT applied only to goods.

There was a separate service tax, which got added on since the production of goods involves some services as well. VAT also did not cover inter-state transactions. So, though cascading was reduced significantly, it was not eliminated altogether.

The National Council for Applied Economic Research (NCAER) has estimated that the implementation of GST will boost GDP by between 0.9 per cent and 1.7 per cent.

The history of GST in India

The initiative for GST started soon after the implementation of VAT in 2005. Then Finance Minister P. Chidambaram announced, in his Budget speech in February 2007, that GST would be implemented from April 2010.

The Empowered Committee of State Finance Ministers started work on drawing up a roadmap. A broad agreement was arrived at on GST being a dual tax—a central and state GST; barring a few agreed exemptions, all goods and services will be brought under GST through a common legislation; there would be no distinction between goods and services.

A Constitution amendment bill was tabled in 2011 to enable GST. This was required because the Constitution does not allow states to tax services and the Centre to tax sales of goods. The Parliamentary Standing Committee on Finance submitted its report on the bill in 2013. A revised bill is to be tabled by the present government.

Who stands to lose

Not all states are keen on GST. With one single tax and rate, they will have to give up their freedom to levy taxes, an important element of fiscal autonomy. States’ own taxes form a significant chunk of their revenues.

Right now, they levy a number of taxes (entry tax/octroi, luxury tax, entertainment tax, taxes on lottery/gambling, purchase tax) and these would get incorporated into GST. This, they fear, will be detrimental to state finances.

State governments want to be compensated for losses they suffer due to GST and an independent compensation system to be institutionalised so that the Centre will not be able to shortchange them. Many also want certain items like petroleum products, items containing alcohol and tobacco products to be kept out of GST.

However, economists have said that GST would be meaningless if this was done. Everything will now depend on the revenue-neutral rate (the rate at which there will be no revenue loss to states) that will be fixed as well as the compensation amount and mechanism for it.

If there is agreement on these issues, GST will be a shoo-in. However, it is unlikely to happen from April 2015. The revised bill has to be cleared by the cabinet and then go through the parliamentary process.

International experience

India is coming to the game pretty late. Nearly 140 countries have a GST system in place, though the models may vary. These include Canada, China, New Zealand, Singapore, Japan and the Scandinavian countries. The European Union has a single rate VAT system that applies to all its members.

Each country gets to keep the VAT levied on purchases within its area. Countries with GST have seen a rise in revenues after its adoption.

Seetha is a senior journalist and author