Heritage

What Recent Evidence Says About The Lost Tongue Of A Multilingual Harappa

Aravindan Neelakandan

Jul 15, 2025, 04:17 PM | Updated Sep 01, 2025, 03:36 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Of all the great questions in human history, few have been as fiercely debated as the origin of the Indo-European languages. This ancient linguistic tree grew from one mysterious root: Proto-Indo-European (PIE), a painstakingly constructed hypothetical language, the matriarch of a language family lost to time.

For over two centuries, scholars have waged a fierce intellectual war to uncover its cradle — the fabled homeland known as the Urheimat. This is a search that goes far beyond an academic puzzle. It is a battleground where modern ideologies clash, each vying to claim this ancient origin.

Ultimately, to trace this language family to its source and follow its evolution across time and space is to grapple with more than history. It is to confront questions of identity and the vested interests of ideologies that define our world even today.

For decades, one narrative has largely dominated the discourse: the Steppe hypothesis. In the Indian context, it has been known for nearly two centuries as the Aryan Invasion Theory, and later, with broader scholarly consensus, as the Indo-European Migration Theory.

The hypothesis presents a dramatic picture of horse-riding pastoralists from the Pontic-Caspian Steppe, north of the Black and Caspian Seas. These horse-borne men, beginning some 6,000 years ago, expanded in a series of waves, carrying their language and genes across Eurasia.

A key part of this story has been the dispersal of the Indo-Iranian branch. The charioteering warriors, ancestors of both Iranians and the Vedic people of India, thundered southwards from the Steppe. Their arrival in South Asia marked a definitive cultural and linguistic rupture.

This is a powerful, compelling, and captivating scenario.

The case against the Vedic Indra for the ‘massacre’ at Mohenjo-daro was famously dismissed by the more detailed archaeology of George Dales. It served as a classic reminder that the most compelling stories are seldom the most complete.

Yet, the invasion narrative is resilient. It found new life in genetics with a 2001 paper by Bamshad et al. linking an Indo-European intrusion and its subsequent impact in shaping the hierarchy of the caste system.

This, however, was soon challenged by larger studies, including a 2003 paper by Toomas Kivisild et al., which disputed the link between a haplogroup and the ‘putative Indo-Aryan invasion’. This cycle of assertion, rebuttal, and refinement defines the field.

The result is a decades-long game of academic ping-pong. The objective does not seem to be to score a final point, but rather to allow a continuous revelation of a past far more complex than any single theory can accommodate.

Then in 2019, a team of 93 scientists collaborated and studied the genome-wide ancient DNA data from 523 individuals spanning the last 8,000 years, mostly from Central Asia and northern South Asia.

The paper published in 2019 declared that it provided ‘evidence against an Iranian plateau origin for Indo-European languages in South Asia but also evidence for the theory that these languages spread from the Steppe.’ That seemed to settle things definitely.

The prevailing Steppe model is built on a tripartite foundation of linguistics, archaeology, and genetics.

Linguistically, the model relies on the pronounced similarity between the oldest attested Iranian language, Avestan, and the oldest Indic language, Vedic Sanskrit. This closeness has traditionally been interpreted as evidence for a very late split from a common Proto-Indo-Iranian (PIIr) ancestor, typically dated to no earlier than 2500–2000 BCE.

This late linguistic date is then correlated with the archaeological expansion of the Eurasian Steppe into Central Asia during the 2nd millennium BCE.

Genetically, this event is marked by the arrival of 'Steppe ancestry'—specifically, ancestry related to Middle-to-Late Bronze Age (Steppe_MLBA) populations—in 'South Asia.' This genetic influx, which is not attested before 2000 BCE and peaks between 1500–1000 BCE, is presented as the demographic vehicle that carried Indo-Aryan languages into the subcontinent.

Thus the language, the people, and the material culture arrived together in a relatively late, cohesive migratory wave. So that should have settled it. The Aryan/Indo-European invasion was real.

Only it did not.

Now, a confluence of two new studies based on palaeogenomics and computational linguistics seems to challenge conclusively the Steppe hypothesis.

A study mapping the genetic roots and trajectories of Indian population with unprecedented detail has been done by Elise Kerdoncuff et al. (University of California). This study, when combined with another 2023 study recalibrating the timeline of language evolution, seems to converge onto what may be an altogether different scenario.

This new emerging view suggests that the Steppe was not the ultimate source for all branches of Indo-European, particularly Indo-Iranian.

The evolution of the Indo-Iranian languages in India was not one of sudden conquest, but a far more ancient and intricate movement rooted in the soil, spread by farmers, and blossoming within a surprisingly cosmopolitan Bronze Age world.

The evidence points away from the Steppe and suggests a very gradual move towards the bustling, multilingual cities of the Harappan civilisation and its peripheral centres, where the first whispers of what would become Sanskrit might have emerged from the mingling of Indo-Iranian with a host of languages from other language families.

This is not entirely a radically new hypothesis.

There has been a main alternative rival to the Steppe hypothesis that proposes that PIE originated much earlier (around 7000 BCE) with early farmers in Anatolia (modern-day Turkey).

Proposed mainly by archaeologist Colin Renfrew in 1987, this view hypothesises that the Indo-European language spread and diversification was more peaceful and happened alongside the spread of agriculture.

Steppe marauders with robust evidence seemed to have defeated the more peaceful Anatolian farmers.

In 2019, a team of archaeologists and geneticists, which included Vasant Shinde and David Reich among others, analysed a single genome from the Rakhigarhi cemetery, a significant IVC site.

The results rejected the possibility of the Anatolian farmer hypothesis for the spread of Indo-Iranian languages into South Asia contemporaneous with the IVC.

Their findings revealed an individual with ancestry derived from ancient Iranians and Southeast Asian hunter-gatherers. But the absence of Anatolian farmer ancestry in the IVC individual, and the distinctness of their Iranian-related ancestry, pointed away from a farming-related language spread from the West.

Instead, the results pointed to a later migration from the Steppe, during the first half of the 2nd millennium BCE, as the most plausible route for the introduction of Indo-European languages into South Asia.

But now an entirely new way of looking at the entire question is becoming possible.

A New Clock for Ancient Tongues: The Hybrid Hypothesis

The first major challenge to the traditional Steppe-centric model for Indo-Iranian languages came not purely from genetics, but from a comprehensive, primarily linguistic re-analysis published in 2023 by a team led by Paul Heggarty.

Their work, Language trees with sampled ancestors support an early origin of the Indo-European languages, tackled a fundamental problem that had skewed previous phylogenetic studies.

Earlier models often forced ancient languages, like Classical Latin or Vedic Sanskrit, to be the direct ancestors of their modern relatives. This seemed logical, but as the Heggarty team argued, it led to historical incongruities.

Heggarty and his team of over 80 specialists at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology built an enormous new database of Indo-European Cognate Relationships (IE-CoR), with 161 languages meticulously studied and coded.

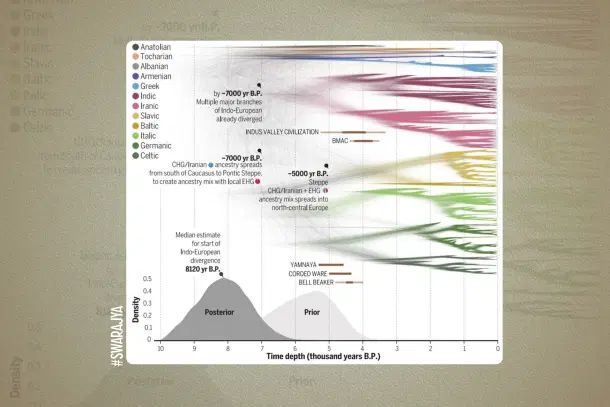

They applied a more flexible model that allowed ancient languages to be either direct ancestors or closely related sister lineages. The results were stunning.

Freed from these artificial constraints, the linguistic clock was reset. According to the analysis, the divergence of the Indo-European family is now placed at circa 8,120 years before present (BP), a considerable revision of previous timelines.

This date is far too early to be compatible with an ultimate origin on the Steppe, which is associated with cultures emerging thousands of years later. Heggarty and his team argue for an initial homeland south of the Caucasus, in the northern arc of the Fertile Crescent, the cradle of agriculture.

As per this model, from this region, the earliest branches of Indo-European began to spread.

According to this model, the Steppe was not the Urheimat, but a secondary homeland. One branch of Indo-European speakers migrated northwards into the Steppe, and it was from there that they later expanded into much of Europe, carrying with them the ancestors of the Celtic, Germanic, Italic, and Balto-Slavic languages.

This elegantly explains the strong Steppe genetic signal found in ancient European populations.

But what of the other branches?

Heggarty et al.'s analysis shows that many, including Anatolian (the language of the Hittites), Greek, Armenian, and, most crucially for the Indian context, the Indo-Iranian, all split off from the main tree long before the major Steppe expansions.

The analysis places the split of the Indo-Iranian branch from the rest of the Indo-European family at circa 6,980 BP. A further 1,500 years later, around 5,520 BP, this branch itself began to diverge into what would become the Indic (Indo-Aryan) and Iranic languages.

With regard to the 2019 paper that almost conclusively proved a Steppe-based spread of Indo-European languages into South Asia, the paper observed:

Recent aDNA data from Central and South Asia have sought to trace movements of people into Western and South Asia by migrations southward from the steppe. However, for the period 4300–3700 yr B.P., samples from the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC) do not yet attest to any such southward migration (V. M. Narasimhan et al). Steppe ancestry is not found until ~3500 yr B.P., in the Gandhara Grave Culture in northern Pakistan, and only at limited proportions. The interpretation that this ancestry can be identified with the first Indo-Iranic dispersal into South Asia is not straightforwardly compatible with our earlier date for the separation of Indo-Iranic from the rest of Indo-European (~6980 yr B.P.). We also find that Indic and Iranic had diverged from each other already by ~5520 yr B.P. (4540 to 6800 yr B.P.). To reconcile this with a steppe origin would require an alternative scenario in which Indic and Iranic split from each other approximately two millennia before entering South Asia and Western AsiaPaul Heggarty, 2023

Thus the timeline is a direct challenge to the Steppe hypothesis for South Asia.

If the ancestors of the Vedic people and Iranians were already a distinct linguistic group nearly 7,000 years ago, and were beginning to go their separate ways by 5,500 years ago, how could their languages have been carried into Iran and India by Steppe pastoralists whose major southward migrations occurred thousands of years later?

The linguistic clock proposed by Heggarty et al. suggests the Indo-Iranians had already left long before the 'charioteers' arrived from the Steppe.

So the languages must have been carried by a different people, at a different time. But who?

Unravelling India's Genetic Past

The answer to that question may lie in the largest and most comprehensive study of Indian genetics ever undertaken.

Published in 2025 by Elise Kerdoncuff and a vast team of collaborators, 50,000 years of evolutionary history of India: Impact on health and disease variation presents a fine-grained map of the subcontinent's genetic landscape, drawn from the whole-genome sequences of 2,762 individuals.

This immense dataset captures the genetic diversity across most of India's geographic regions, language groups, and social communities, including historically underrepresented ones.

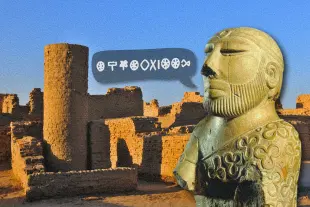

The study confirms and refines a picture that has been emerging for years: the genetic makeup of most modern Indians is constituted from three primary ancestral components.

The first is an indigenous lineage of South Asian hunter-gatherers, sometimes referred to as 'Ancient Ancestral South Indians' (AASI).

The other is an ancestry from pastoralists who did indeed come from the Eurasian Steppe.

But it is the third component that is the most critical here: a major stream of ancestry related to Neolithic farmers from Iran and Central Asia. This predates Steppe admixture.

And this admixture created some of the deep, persistent changes in Indian society. The authors write:

By examining data from 14 ancient Iranian groups from the Neolithic to the Iron Age, we uncovered a common source of Iranian-farmer ancestry related to 4th-millennium BCE farmers and herders from Tajikistan (Sarazm_EN, ∼3,600–3,500 BCE) into the ancestors of ASI, ANI, Austro-asiatic-related, and East Asian-related groups in India. Archaeological studies have also documented trade connections between Sarazm and South Asia, including connections with agricultural sites of Mehrgarh and the early Indus Valley civilization.... Following these admixtures, India experienced a major demographic shift toward endogamy, resulting in extensive homozygosity and Identity-By-Descent sharing among individuals.Kerdoncuff et al

So long before Steppe intrusion, which in itself was perhaps not massive, endogamous communities had started consolidating themselves.

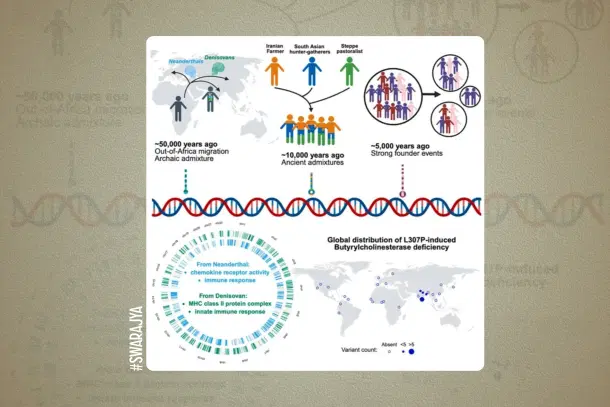

Using sophisticated modelling techniques (like qpAdm, which tests which combination of ancient populations best reconstructs the DNA of a target population), Kerdoncuff et al. searched for the best-fitting 'proxy' for this Iranian farmer component among a wide array of ancient DNA samples.

They compared Indian genomes to 14 ancient populations from Central Asia and the Middle East. Their analysis identified the population of the 4th millennium BCE (Chalcolithic) proto-urban site of Sarazm in Tajikistan as the closest available proxy for this source population.

Whether looking at the ancestors of the northern 'Ancestral North Indians' (ANI) or the southern 'Ancestral South Indians' (ASI), the model with Sarazm_EN (for Sarazm Early Neolithic) provided the most robust fit.

This was not just a statistical abstraction.

Sarazm, a UNESCO World Heritage site, was a proto-urban centre, a vital node of agriculture and metallurgy in Bronze Age Central Asia.

It is a site on the northeastern periphery of the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC) cultural zone.

As Kerdoncuff et al. highlight, archaeology has already documented strong trade connections between Sarazm and South Asia.

The link is astonishingly direct. One of the ancient individuals analysed from Sarazm was discovered buried with shell bangles that are identical in design to those found at Harappan sites like Surkotada in Gujarat and Shahi-Tump in Makran.

The genetic trail and the archaeological trail were leading to the same place, at the same time. People from Central Asian farming communities like Sarazm were doing more than trade with the Indus Valley Civilisation. They were interacting with it, and almost certainly moving into it, bringing their genes with them.

The genetic profile of this same Sarazm_EN individual with IVC-style bangles revealed that this person possessed approximately 15 per cent ancestry related to the indigenous hunter-gatherers of South Asia (AHG/AASI). This is a landmark discovery.

It proves that gene flow was not exclusively a one-way street from west to east. People with deep South Asian roots were moving into Central Asia and mixing with local populations during the Neolithic.

This finding transforms the model from a simple 'migration' into a sustained 'interaction sphere', a vast zone of persistent contact, trade, and intermarriage.

The Kerdoncuff study is also a treasure trove of other insights.

It reveals that the primary settlement of India by modern humans from Africa was a single, major event around 50,000 years ago. It shows that Indians harbour the largest variation and the highest amount of population-specific Neanderthal ancestry of any group worldwide, a testament to the deep and complex history of the larger Indian landmass.

And it details how a history of endogamy (marriage within communities) and founder events has led to high levels of homozygosity, where individuals inherit identical segments of DNA from both parents, which has important implications for recessive disease risk today.

But for the story of the Indo-Iranian languages, the key takeaway is the clear, strong, and widespread contact and interaction of the people of Sarazm and the people of IVC.

A Grand Synthesis: Where Genes and Languages Meet

When placed side by side, the linguistic evidence from Heggarty et al. and the genetic evidence from Kerdoncuff et al. tend to resemble two fitting pieces of a puzzle, forming a new and coherent picture.

The Heggarty timeline creates a chronological problem for the Steppe hypothesis in South Asia. Indo-Iranian languages were already diversifying by circa 5,520 BP, long before the main Steppe-related migrations started becoming genetically visible in the subcontinent (around circa 3,500 BP).

At the same time, the Heggarty framework makes Sarazm a potential staging ground for the final divergence of the Indo-Iranian family. A population of early Indo-Iranian speakers in the prosperous Sarazm region could have emerged around 3500 BCE.

This date corresponds precisely with the early occupation phases of Sarazm, which was a flourishing proto-urban centre from the 4th millennium BCE onwards (circa 3500–2000 BCE).

The Kerdoncuff genetic data perhaps provides a new model for the language's transmission: the movement of agriculturalists and deep interactions of groups.

The Sarazm proxy, dated to the 4th millennium BCE (circa 5,500 years ago), aligns perfectly with the linguistic timeline for the initial divergence of Indic and Iranic languages.

This was not a story of pastoralist conquerors, but a slower, more sustained process of farmers moving into new lands, following trade routes, and settling alongside existing populations.

Witzel's Lost Language of BMAC

Harvard Indologist Michael Witzel has drawn attention to what he called 'old Indian and old Iranian texts that do not seem to be of Proto-Indo-Iranian... origin'.

He identifies a set of what he terms 'leitfossils'—words for technologies and items characteristic of the BMAC but foreign to the incoming Steppe cultures.

Witzel's framework is that Indo-Iranian was brought into BMAC by Steppe migrants. Thus, while BMAC was a civilisation of mud-brick architecture, the Yamnaya were not. So the word for brick in Vedic language iṣṭi-, and Avestan ištiia-, were loan words they obtained from the now-lost language of BMAC.

The same was true for camel (úṣṭra) and donkey (khára). Witzel claims that even the very core of Vedic religion—Indra and Soma—was obtained from a pre-Indo-Iranian substrate of a lost BMAC language. (Witzel, 'Linguistic Evidence for Cultural Exchange in Prehistoric Western Central Asia', Sino-Platonic Papers, 129, 2003).

But if one abandons the Steppe dispersal of Indo-Iranian and instead considers the Heggarty framework, the presence of Indo-Iranian right from Sarazm and throughout the evolution of BMAC naturally allows this branch of the language to evolve vocabulary for the technologies and fauna of Sarazm and IVC.

The religion, then, was not appropriated but evolved uniquely here.

The shared vocabulary identified by Witzel must therefore be significantly older, predating the split of the two branches.

The findings of Kerdoncuff et al. establish a concrete Sarazm-Indus interaction corridor during the Neolithic and Bronze Age, a space of movement and admixture that was active long before the Steppe migrations.

This provides a plausible geographical and demographic context for the early divergence of the Indo-Iranian languages proposed by Heggarty et al.

It shifts the focus of early Indo-Iranian history away from the northern steppes and places it squarely within the southern Central Asian zone of interaction that included the established Sarazm and IVC as well as the evolving BMAC region.

Perhaps what Witzel observed could be a complex dialect continuum within the early Indo-Iranian world that could well have included IVC.

Given the deep time depth of over a millennium between the initial Indo-Iranian split (circa 4980 BCE) and the divergence of Indic and Iranic (circa 3520 BCE), the development of significant dialectal variation is not only plausible but expected.

What Witzel interprets as the fingerprints of a lost non-IE language may in fact be the echoes of a rich, internal dialectal diversity within the early Indo-Iranian family itself, a diversity that was later levelled out by the expansion of the specific dialects that became Vedic and Avestan.

This does not mean the Steppe migration did not happen.

The genetic evidence from Kerdoncuff and others is clear that it did. But it was a later event.

This later wave of Steppe pastoralist ancestry into an already complex subcontinent may have brought other, related Indo-European dialects, or perhaps it reinforced the status of Indo-Aryan languages that were already present.

It may have contributed to the formation of the later Vedic culture. But it was not the originating event. It was a later chapter in a book whose first pages had been written centuries, or even millennia, earlier by farming communities.

Parpola's Intra-Aryan Holy Wars

If Witzel posits a process of substrate-driven acculturation, Finn Dravidianologist Asko Parpola proposes a more complex scenario of multi-wave migration and intra-Aryan syncretism.

In this view, the primary cultural fusions and conflicts that defined early Indo-Aryan identity occurred on BMAC soil between distinct waves of Aryan-speaking groups, each with different religious cults.

The two models offer opposing interpretations of the religious vocabulary.

Witzel views the presence of words like Indra, Śarva, and anću (Soma) in his substrate lexicon as clear evidence that the Indo-Iranian speakers adopted foreign gods and the central element of their main ritual from the BMAC population.

Parpola interprets the religious differences—Asura-worship versus Deva-worship, the absence versus the presence of the Soma cult—as evidence of an internal divergence that occurred within the wider Aryan-speaking world.

The Soma cult was not borrowed from a foreign people; it was the unique patrimony of a specific branch of Aryans, the 'Sauma-Aryans'.

Although Parpola and Witzel concur that Steppe peoples introduced Indo-European languages to the region, they diverge on the origins of key Vedic vocabulary.

While Witzel sees it as a borrowing from a 'lost' BMAC language, Parpola points to the possibility that it could be an internal evolution within the Indo-Aryan cultural sphere with multiple invasions.

Witzel sees the entry of Indo-Iranian as a gradual process rather than a single, massive invasion. It happened over a centuries-long process: circa 2100–1600 BCE.

On the other hand, Parpola proposes 'two waves of Proto-Indo-Aryans that came to the BMAC around 2000–1900 BCE and 1700–1600 BCE' (The Roots of Hinduism, 2015, p. 300).

As discussed earlier, in the light of the timeline provided by Heggarty et al., this invasionist scenario must be replaced with a broader model of settled interactions prolonged over millennia, covering a larger landmass.

This expanded timeline lends considerable credence to a model of such a protracted internal evolution.

A multi-millennial history of migration and divergence provides the necessary historical space for the complex, multi-stage process of cultural formation that Parpola envisions.

It makes plausible a long-term synthesis wherein diverse ethnicities, competing religious systems, and distinct dialects could interact, clash, and ultimately merge across the vast Bronze Age landscape connecting the BMAC, its periphery at Sarazm, and the Indus-Saraswati valley, forging the complex and layered Vedic worldview.

What about the 2019 Study of Rakhigarhi Genome?

In the phylogenetic analysis of Heggarty et al., the ancestral homeland of Proto-Indo-European (PIE) is not on the Steppe, but south of the Caucasus and in the northern arc of the Fertile Crescent, which includes the Zagros Mountains.

From this locus, which is the source of the Caucasus hunter-gatherer/Iranian (CHG/Iranian) genetic component, some branches of Indo-European spread north to the Steppe, a secondary homeland.

This is highly suggestive of the possibility of others spreading out east.

With Indo-Iranian diverging around 6,980 years before present and the Indic-Iranic split by 5,520 years before present, these linguistic events predate the mature phase of the IVC (circa 2600–1900 BCE).

The population of the IVC, as represented by the Rakhigarhi genome and the 'Indus Periphery Cline', was a mixture of Iranian-related and South Asian hunter-gatherer ancestries.

The Kerdoncuff et al. study traces this Iranian-related ancestry to Central Asian farmers from Sarazm, who were contemporaries of the early IVC and had documented cultural and trade links.

Naturally, Indo-Iranian languages might have been present in IVC, though they might not have been the sole languages.

While the 2019 paper by Shinde et al. was crucial in demonstrating the lack of Steppe as well as Anatolian ancestry during the height of the IVC, the subsequent linguistic and genomic studies provide a more intricate picture.

The focus has shifted from a single, late migration to a more ancient and multifaceted process in which the Indo-Iranian evolving into a Vedic language would have been a completely autochthonous phenomenon in the Indus-Saraswati valley.

Re-imagining Harappa: A Multilingual Metropolis

This synthesis has its most profound implications for how the Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC) or Indus-Saraswati Civilisation (ISC) is viewed.

Flourishing from circa 3300 BCE, this vast urban culture, larger than ancient Egypt or Mesopotamia, has long been one of history's great enigmas.

Its script remains undeciphered, and thus the language or languages its people spoke are unknown.

The traditional Steppe model implied a completely non-Indo-European Harappa, a civilisation that was ultimately overthrown or displaced by incoming Indo-Aryan speakers.

The new evidence invites us to relook at this model.

If people with farmer ancestry from Central Asia, with demonstrable links to sites like Sarazm, were moving in and out of the Indus region from the 4th millennium BCE onwards, and if the linguistic timeline suggests they could have been speaking an early form of Indo-Iranian, then the Harappan world was almost certainly not monolingual.

The great cities of Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa were likely cosmopolitan hubs, melting pots of people and languages.

We can imagine the bustling streets filled with the sounds of various tongues. There would have been languages which harboured major sources of linguistic elements that would become the modern Dravidian languages, or other language families now lost to time.

And equally co-existing with them, in communities of traders, artisans, and farmers, could well have been an early form of Indo-Iranian.

There is a strong possibility that the language that we know today as Sanskrit, in its proto-form, evolved here.

Kerdoncuff et al.'s paper hints at this complexity with its mention of the 'Indus Periphery Cline', a collection of ancient individuals from sites on the edge of the IVC who show a mix of Iranian farmer and indigenous South Asian hunter-gatherer ancestry.

This is the genetic signature of admixture, of different peoples coming together.

Where genes mix and languages meet, a grand civilisation evolved.

The IVC was not a uniform entity waiting for a linguistic takeover. It was a dynamic civilisation built on interaction and exchange, a process in which language would have been a key component.

A New, More Complex Past

The science of human origins is undergoing a profound transformation. Simple narratives of monolithic migrations and conquests are giving way to more nuanced, and ultimately more realistic, models of our past.

The story of how the Indo-Iranian and Indic languages evolved in the larger Indian landmass is a prime example of this shift.

The work of Kerdoncuff et al., when viewed in the framework of Heggarty et al., seems to displace the idea that the IE language was brought by Steppe pastoralists.

Instead, the evidence points to a more ancient, farm-based expansion whose epicentre seems to move more and more towards the east, carried by people genetically similar to the Bronze Age inhabitants of Sarazm.

This new framework may challenge long-held ideological positions.

For instance, the possibility of an Urheimat located outside of India, or Sanskrit as not the mother of IE but just a branch, might be met with resistance from a section of Hindutvaites.

Just as the possibility of emergence of endogamous groups long before the so-called Steppe intrusion will be unsettling to Dravidianist ideologues who want to identify the Brahmins as the chief culprits of the caste system and associate that with the arrival of Aryan marauders from the Steppe.

However, the journey of the Indo-Iranian languages was not singular, and definitely not a dramatic event originating from the Steppe.

Instead, it was a meandering river with numerous tributaries, its ultimate source still veiled in mystery.

We now understand that its currents merged with other streams within the Indus Valley, a process that likely began at the dawn of the Harappan civilisation itself and continued throughout, even facilitating its evolution.

This was a civilisation of such complexity that we have only just begun to grasp its full measure over the past century.

The complete narrative of our origins is still unfolding, etched in the cognates of our words and the very code of our DNA.

Yet, the emerging picture is undeniable. Our past is invariably richer, more intricate, and more fascinating than the simplified tales we often hear from others and then tell ourselves.

From its inception, this civilisation has seen a comingling of languages, ethnicities, and rich theo-diversity. It appears that from the very beginning, a core set of values provided cohesion while simultaneously nurturing this variety.

It is an oneness that shines through diversity, a unity that facilitates multiplicity, and a diversity held together by that oneness (Bhagavad Gita 13:31).

This fundamental realisation of oneness in the celebration of diversity is what we call Bharatiyata—our shared Indianness.