Ideas

The First Quarter Billion Doses: Looking Back And Ahead

Suraj S

Jun 10, 2021, 12:55 PM | Updated 05:44 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

By the end of this week, India will reach the milestone of 250 million doses of COVID-19 vaccinations performed. The vaccination of the general public, beginning with the age group of over 60 and those between 45-60 with comorbidities, began on 1 March 2021. Up to that point, a total of 14.3 million vaccinations to all the healthcare workers (HCWs) and frontline workers (FLWs) had been performed.

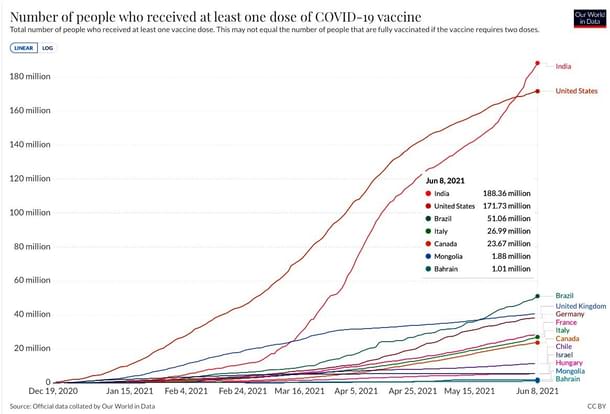

With no reliable data from China being reported, the popular data aggregation website ourworldindata.org shows that India now also holds the distinction of having the largest verified population with at least one vaccine dose.

Vaccinations And The Second Wave

The relatively short but traumatic COVID-19 second wave stressed the medical system to the breaking point. States strove to take control of the vaccination process, mistakenly identifying the central distribution system as the cause of what they saw as slow or nonoptimal vaccine supply.

Several Opposition leaders wrote public letters asking for states to be allowed to procure vaccines directly, including Mamata Banerjee on 24 February 2021 and Rahul Gandhi on 9 April 2021 (INC press release).

While seemingly proactive, these demands fail to recognize a few fundamental issues -a) demand far exceeds the supply of vaccines anywhere. b) central governments have much greater negotiating power than a group of state governments. c) companies cannot and should not be forced to decide which states to prioritize vaccines to.

Yet, due to the stridency of the demands, the government acceded. On 19 April, the new Liberalized and Accelerated Phase 3 Strategy was announced enabling states and private parties to procure 50 per cent of monthly production by the vaccine makers from 1 May 2021. It also announced a new policy structure for foreign vaccines to conduct accelerated trials in India on 15 April 2021.

Predictably, the state-led mechanism did poorly. Several factors combined to hamper them. Different states had different financial means to place orders. Deliveries showed zonal variations as companies struggled to keep everyone happy.

Global tenders by several states—Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, Punjab and more—drew a blank or received Expression of Interest (EOIs) from sketchy middlemen. Moderna informed Punjab they would only deal with the central government.

On 8 June 2021, the government announced the end of this programme. The centre would once again control the procurement of at least 75 per cent of production, with the rest available to private parties. The centre would further expand eligibility to those 18 and over.

Production: Beginning Of Volume

A seldom appreciated fact is that stockpiles are what have sustained Indian vaccine consumption since March. Adding domestic consumption, exports (until stopped in April), wastage and content in the pipeline, the monthly total exceeds the known production rate for those months.

This was addressed from stockpiles as described in my prior article. The article also warned about how May would be a difficult moment as stockpiles were used up even as production increases were only likely at the end of May or June. This is essentially what happened.

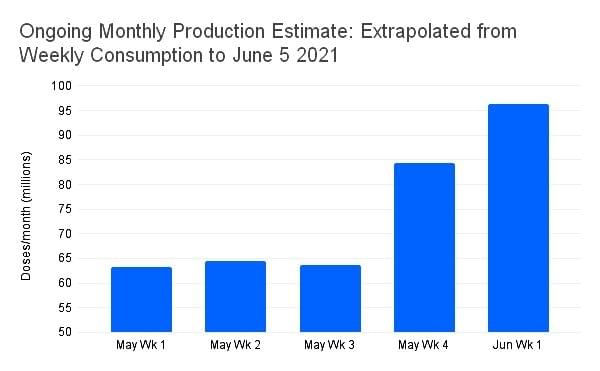

Now, we see the impact of greater volume. Production on any given day takes around three to four weeks to be consumed currently. The entire production period is approximately four months long for Covaxin. Taking weekly consumption and projecting an ongoing monthly production rate by applying wastage and volume still in the pipeline, the following chart emerges:

This graph shows the following detail:

- By the end of April, the available stockpile was indeed placing pressure on the vaccination rate in early May.

- Production volume began increasing start of May, visible as consumption by the end of the month.

-June first week consumption rate suggests mid-May achieved production rate close to 100 million doses.

The projection of current production capacity will be confirmed if ongoing June vaccinations continue or increase. Early data to 8 June shows that the second week of June has seen 26 per cent more vaccinations than the first week. This is a positive sign that June is headed for more than 100 million doses production, which would be the highest monthly production to date.

Orders: Closely Aligned to Production

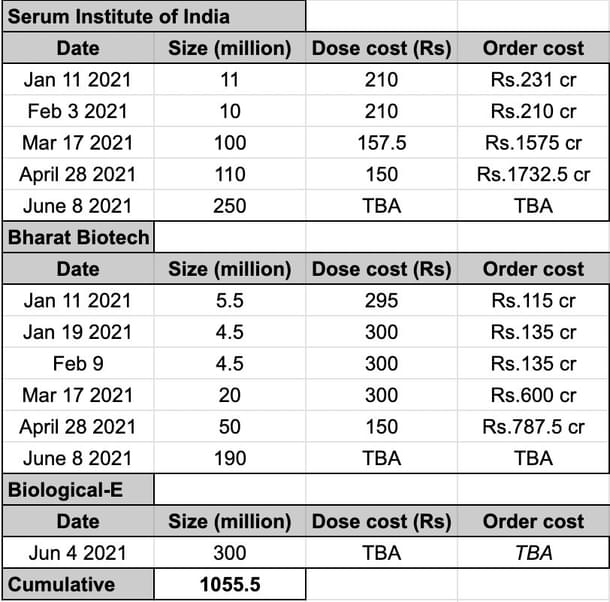

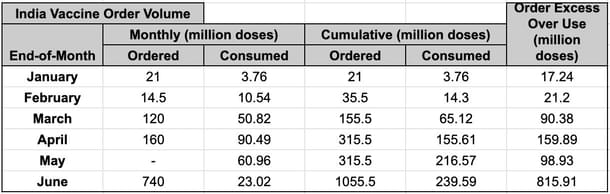

Order volume to date is closely aligned to the estimated production rate. This is seen in the orders made by the central government so far. Since March, orders have come at a six-week cadence. This suggests that the volume ordered is produced over six weeks. Examining in more detail:

Covishield 100 million over six weeks in March implies monthly (month equals four weeks) = 100 * 4 / 6, or 66 million/month, close to the ~60 million doses/month known production rate then.

Similarly, Covaxin 20 million March order corresponds to an estimated production rate of 20 * 4 /6 = 13 million, which is close to the 10-15 million production rate known for March.

April order sizes are larger than March ones, reflecting an increase in production capacity by the end of April, as shown from consumption-based extrapolation seen in Figure 2.

The June orders have broken new ground—their sheer volume—74 crore doses vs 31.5 crore in combined orders up to then, indicates a concerted push to enable acceleration in supply and the need for additional capex from the companies.

A consistent argument made is why does the government not make extremely large orders as the EU has done? The counterargument to that is - where is data showing the EU gained from that approach? Is this claim just a convenient trope, or is there data? Let us look:

Data above shows India has been getting delivery volumes of 100 million doses within 1.5-2 months from the order date. My previous article on bulk ordering shows that Pfizer orders of 100 million doses take a minimum of seven to nine months to fulfil, and that is for the US/EU, which both have Pfizer plants that supplies can be trucked from. Japan ordered 120 million doses of Pfizer in July 2020 and has to date, done 18 million doses of Pfizer and Moderna combined.

Despite being amongst the earliest to get EUA, Pfizer struggled with production yields in January, producing only 4 million doses per week even as the US saw over 3000 deaths per day then.

The argument for huge order sizes is unsupported by any data proving that it has accelerated deliveries or reduced turnaround to delivery. Availability is constrained by production challenges and not a “lack of orders”; there is no lack of demand for the foreseeable future.

Several advanced countries have enough order volume to vaccinate themselves every two months, but actual deliveries have no foreseeable schedule, given over a billion orders are for vaccines yet to clear trials (e.g. Novavax, Valneva, Sanofi).

New Vaccine Candidates: Hands-On Support

The next few months may see new Indian vaccine candidates clearing Phase III. Biological-E’s candidate CorbeVax is due to complete Phase III in June/July and anticipates EUA soon after. The company estimates up to 70 million doses/month production as soon as August. To ensure they can do this, the government has placed a substantial 30 crore dose order to give them cash upfront for capex.

Zycov-D, the novel DNA-based vaccine, is currently in Phase III. As with CorbeVax, the government may place an order for them as soon as there’s clarity on efficacy.

These follow a pattern of sustained interaction with all domestic vaccine makers dating back to early 2020; in November, the Prime Minister toured the facilities of all these companies (link, link). These indicate a sustained top-down emphasis on close interaction with companies to enable each step of vaccine development and a readiness to order as soon as something is production-ready.

This is a sensible approach - vaccine development will not accelerate simply because there are more orders, but hands-on support for development, including grants-in-aid investments (Zycov-D, Biological-E), assistance with the expedited import of equipment and raw material, and even funding of Phase III trials, can all measurably accelerate the process. Focusing on supporting and accelerating procedural steps is better than simply thinking of "orders".

The latest data indicates the difficult period of vaccine supply, and demand imbalance is now nearly past. The strong increase in vaccination numbers for the past two and half weeks aligns closely with the statements made by the vaccine manufacturers that supply would rise by the end of May. From 250 million by the end of this week, India will see probably over 300 million doses consumed by the end of the month.

The government has chosen a judicious process of working closely with vaccine makers, supporting them every step of the way. Both the availability—and potential bottlenecks as seen in May—have so far been predictable ahead of time from the available data that has been presented.

This offers a level of confidence in the supply availability, at least for the near future, and suggests that at least the established vaccine production lines will continue to manage the scaling aims they have publicly stated. If the new vaccine candidates also manage to start production on schedule, that would be a great bonus.