Obit

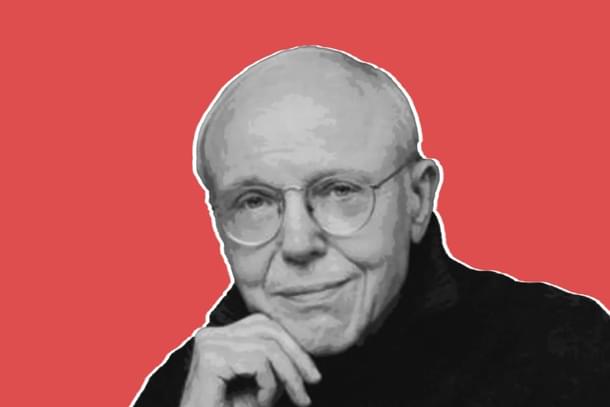

McKim Marriott (1924-2024): A Farewell Of Gratitude And Indebtedness

Aravindan Neelakandan

Aug 14, 2024, 01:11 PM | Updated 01:34 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

A Dialogue And A Mind Game

Let us play a small mind game. Consider the following paragraph:

This is because it is necessary for the welfare of this world that [our] portions (amsa) in this world not be equal. Rather one must be greater than another, and one person must be subject to the command of another. This is because if all men were kings, then who would be the kings’ peasants? If all were wealthy, then who would do the work of the wealthy persons’ servants? If all were Brahmins, who would do the work of the artisans? If all were artisans, then who would give work to the artisans. if all were equal, then no one would serve another. No one would accept another’s command, and everyone would do what he like and do bad work without fear, because no one would be chief and no one would have enough divine authority (kudrata) to punish the evil-doers. For this reason, if all people were equal, then there would be a great confusion (ajaguta) in the world.

Now consider the facts.

This is an excerpt from an early eighteenth century work. It was an evangelical work. It was a conversation between an evangelical Christian and his Hindu target — a learned Hindu Pandit.

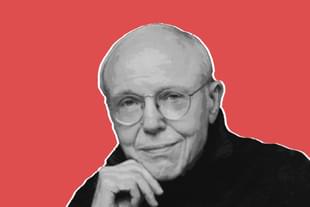

It was published in 1751 in Hindustani language. It was written by Giuseppe Maria Bernini (1709-1761), a dedicated Franciscan missionary, who established one of the earliest communities of Hindu converts to Christianity in north India.

It was later translated in 1787 to Italian. It was translated into English in 2015 by Indologist David Lorenzen.

So the passage is there and so are the facts. Let us play the mind game. Without googling, tell to whom you attributed the above justification of caste system?

If you have played the game honestly, in all probability you should have attributed it to the Hindu target in the dialogue. And you are wrong. This is the theological justification that the Christian evangelist is giving in the tract to the Hindu Pundit.

The target Hindu in that tract actually points out the social inequalities and the inherent injustice in them as the proof of the Karma of previous birth.

If one views the Christian from the point of view of the image we have in the last 150 years of Christianity, then he would be expected to repudiate Karma and rebirth and more importantly caste system.

But here we see the Hindu actually uncomfortable with the inequality which he tries to rationalise with the previous birth but the Christian is more than comfortable with inherent inequality.

What this reveals is that in the pre-modern period the justification of social stratification with religious arguments is a common phenomenon cutting across almost all cultures.

Nevertheless, Hindu Dharma and Hindu society have been singled out by academics and charged with creating a structure of graded inequality or hierarchy while the Western cultures and societies are shown as having a natural propensity towards equality.

The Original Clash Of Civilisations

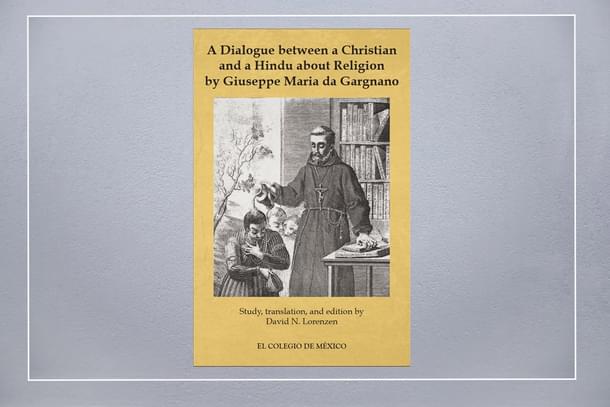

This was put forth strongly by French structuralist anthropologist Louis Dumont (1911-1998). Dumont characterised Hindu society by its hierarchical nature, which he argued stemmed from its spiritual texts and was reinforced by religion.

This hierarchy, according to Dumont, was based on the concept of pollution — both bodily and ritualistic. Thus, he coined the term ‘Homo Hierarchicus’ to describe the Hindu individual.

In stark contrast, he described Western societies as embodying ‘Homo Aequalis’, characterised by notions of individual freedom and equality. He wrote two books with the same titles.

Dumont, in many ways, can be seen as a deep forerunner of Samuel Huntington. He posited a profound dichotomy between Hindu and Western/Christian societies and as an inevitable corollary veritable clash of their spiritual and social values.

This dichotomy between ‘Homo hierarchicus’ and ‘Homo aqualis’ became so popular among the scholars who had harboured a deep colonial mindset in the post-colonial world.

Dumont had provided a post-colonial academic justification to view Indian civilisation as inherently deficient and ethically and spiritually inferior to the West.

As recently as 2019, the influential Nehruvian historian Ramachandra Guha, in his convocation address at the National Academy of Legal Studies and Research (NALSAR) University, invoked Dumont to essentialise Hindu civilisation and society as hierarchical. He then positioned Indian democracy as an unfinished project in opposition to Indian civilisation.

In its more extreme forms, such as those espoused by anti-Hindu ideologue Kancha Ilaiah, this conceptualisation has morphed into hate literature targeting groups like Brahmins, stereotyping them as monolithic and inherently deficient parasites.

Dumont’s clever association of Indian religion and society with biological nomenclature inadvertently created a space for the development of such hate rhetoric. This dark transformation has since permeated much of academia and influential sections of the polity in subsequent decades.

Enter McKim Marriott

In the academic battle field, a contemporaneous voice arose to counter Dumont’s negative portrayal of Hindu civilisation. It was that of anthropologist McKim Marriott (1924-2024). He died on 3 July 2024. His contribution to Indian social sciences is not limited to his critique of Dumont’s theory.

He took formidable steps to create what he called ‘Hindu ethnoscience’. His contribution demands from us Indians more recognition and wider adapted application as well as taking forward. That shall be gratitude no doubt, but also our own civilisational need of the hour.

Here is why that is.

An Advaitic Social Science?

In 1974, an entry on caste in the famous Encyclopaedia Britannica was written by Marriott and his colleague Ronald Inden.

Dumont and his supporters got agitated that this might diminish in value Dumont’s own theory, even though the entry did not criticise Dumont. So they made a strong criticism of the way Marriott explained the caste system.

Marriott and Inden wrote a paper to counter the criticism in the conclusion of which they said this:

In the course of our work, we have developed an increasing respect for the indigenous social sciences and other conceptual systems of South Asia, which are predominantly monistic. Most of the Western natural sciences have passed successfully from dualism to monism, and we expect that Western social scientists will also be able to do so. One way for them to try is to stretch their minds around those conceptual systems of South Asia that already have some of the features that the Western social sciences require. We do not pretend that such a mokṣa like objective is easily attained, but we think it would not be a bad objective for them to make themselves -the knowers-somewhat like those South Asian objects that they would make known.McKim Marriott and Ronald B. Inden, Interpreting Indian Society: A Monistic Alternative to Dumont's Dualism, Journal of Asian Studies, Vol.XXXVI, No.I, November, 1976, p.195

Marriott critiqued the way Dumont depicted Indian society that it was unidimensional and that it was dualistic. The critique was both empirical and conceptual which was deeply rooted in Indian soil.

Regrettably, much of Indian academia, driven more by a blend of cerebral lethargy and ideological biases than a genuine quest for truth, have favoured Dumont over Marriott.

According to Marriott, in Hindu social view, the human being not as an individual "that is indivisible, bounded units, as they are in much of Western social and psychological theory".

Anthropologist Diane Mines explains that for him the Hindus "are divisible persons made up of particulate substances that can flow across boundaries and thus be shared, exchanged, and transferred".

Marriott called the Hindu person more a ‘dividual’ than an ‘individual’ in the Western sense of the term. Hindus are more nodes in the web with their own individual agency with which they participate in that riverine every changing web which is ‘samsara’.

The Hindu aim is to participate with awareness and then withdraw without destroying the web and mostly adding value to the web and move towards moksha. To him Hindu society should be seen in this framework which has as its basis the non-duality.

The most profound insight in his work is this non-dualist understanding of the dynamics of Indian society. He viewed jati as a dynamic structure, whose position within Hindu society is determined not by dualities such as power-status or purity-impurity as framed by Dumont, but through transactions.

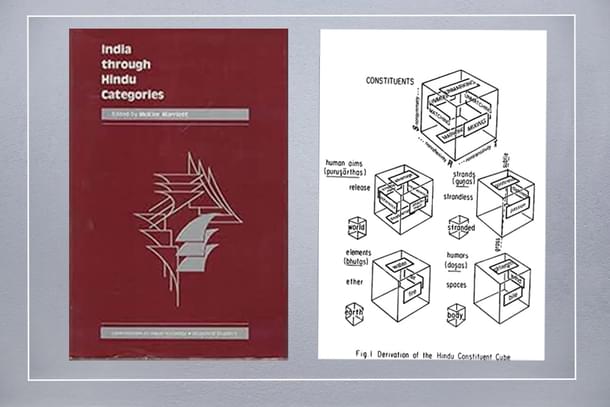

In 1990 came the seminal work which he edited. It was a collection of papers each with brilliant field work and data.

He named the collection, ‘India Through Hindu Categories’ (Sage, 1990). In this collection, in his paper titled "Constructing an Indian Ethnosociology" he pointed out how a Hindu social science would differ from the Western one:

As a people who are etymologically 'riverine', it is serendipitous that Hindus should have a set of sciences that respond so well to hydraulic metaphors.... Unlike points in a Euclidean geometric space, imperfectly bounded fluid entities can never be presumed to be fixed, discrete or absolutely measurable. Modelling Hindu phenomena thus seem to require algorithms more like those used in the sciences of oceanography or meteorology...

Thus in Hindu ethnoscience he was formulating what he saw at its basis:

... the omnipresent, reflexive, nonmaterial, constant process(es) commonly glossed over as 'self' or 'soul' (brahman, atman) or consciousness (purusa). Its function of total, passive consciousness is normally available to humans only on released consciousness, conceivable as the empty and static complement of the universal set (of the foregoing particulars), does a sense of wholeness ordinarily arise. By conceptually aggregating all points of view (those of all differently situated, embodied souls) on a fluid world, however this Hindu notion of a ubiquitous consciousness seems to point to the multiperspectival and multidimensional kind of thought about relationships and processes which a Hindu ethnosociology, too, may well attempt. Such consciousness is, of course, the subject of a vast speculative literature, but has only begun to be a focus of ethnography.

More importantly, he saw this not as limited to Hindu society — kind of an ethnic variant limited in scope. Instead he saw it more as a complementary alternative to be used to counter the biases and distortions that the dominant Western sociology was bringing to non-Western cultures and itself.

Thus Hindu ‘ethno-social science’ according to him is not of value "as a negation of all Western distinctions, and of value only as negation of all Western distinctions", and not "of value only as refutations of the Western ethnosoical sciences' claims to analytic universality" but its integral rather than the dissecting Western approach "often point to alternative, especially transactional concepts of integrative value".

He also created multidimensional cubes as tools in this ethnoscience that he created. It was part of a larger emerging paradigm:

These presuppositions are in many ways also compatible with the findings of current linguistics, of molecular and atomic physics, of ecological biology, and of social systems theory (Buckley 1967; Capra 1975; Marriott 1977; Prigogine and Stengers 1984). They are more compatible than are the presuppositions of Western theology, law or common sense which generally underlie the concepts of conventional Western social science.

The inability to pursue more vigorously on this framework again should be attributed to the deeply colonial Nehruvian-Marxist cerebral mist that has thickly engulfed the social sciences in India.

A very important contribution of Marriott is the way he pointed out how caste hierarchies are more process-dependent and hence transactional than structural and static. They are determined by the tangible and intangible exchange-transactions across the boundaries. This involves genetic, cultural and material exchanges.

The way they happen decides the position of the caste and the individuals. This means jati and varna are no static structures where communities and individuals are imprisoned for millennia through religious rules. They are dynamic and localised flows and webs.

Some Valid Criticisms

There are certain valid criticisms of the work of Marriott.

For example, Prem Saran, an IAS (Indian Administrative Service) officer turned anthropologist has pointed out that both Dumont and Marriott somehow find the Hindu person deficient — either as ‘Homo heirarchicus’ or as a ‘dividual’.

According to him "the Western type of individuality is an integral part of the South Asian cultural reality" and it is the Western centric notion that makes their social sciences deficient in understanding the concepts of individualities like Hindu conception of the individual.

This critique serves as a caution when employing Marriott’s ethnosocial science. Marriott’s concept of the ‘dividual’ allows for the substitution of the Hindu individual with the existential core of their cultural identity. By integrating this individuality with the transactional-exchange perspective of Hindu society, we can offer a compelling vision for both academics and activists.

Another important criticism of Marriott’s model is his reliance on Dharmasastra literature, in addition to empirical field data — a critique he himself directed at Dumont.

Marriott was aware of this limitation in his conceptualisation (though his field work encompassed south India and non-Brahmin communities including scheduled communities). But actually, had he also included Bhakti literature in his conceptualisation it would have only strengthened his model further.

Azhwar To The Rescue

Bhakti literature — both the mystic hymns as well as narratives — shows transactional exchanges across community boundaries fostering more harmonious and egalitarian bonds.

These bonds paradoxically possess the potential to liberate the individual from the web of relationships, leading to moksha, or non-dual liberation.

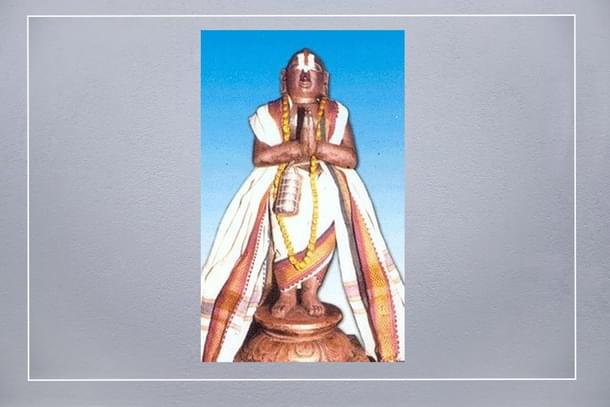

The lines in the hymn of Thondaradipodi Azhwar, one of the 12 Azhwars, make the Bhakti-catalysed, boundary-free exchange of tangible and intangible sacred transactions the hallmark of Dharma.:

Oh the Divine who is enshrined in the walled auspicious grand city of Arangam, You decreed upon the scholarly masters of the four Vedas, the Brahmins of faultless character and noble lineage, that they should venerate on par with Yourself those devotees who are from (what the society considers as) inferior clans, venerate them and also give and take with them.(Nāllāyira Divya Prabandam, First Thousand, verse: 913 )

This verse highlights the dynamic and emancipatory potential within the transactional understanding of Hindu social stratification. It is essential to delve into this perspective.

Rather than viewing Hindu society as an oppressive, anti-democratic, and rigid structure of stratification and exclusion, this approach reveals it as a network of dynamic, stochastic exchanges across semi-permeable boundaries.

When energised by the greater vehicle of Dharma with the aim of moksha, this network becomes a powerful and sustained force for social emancipation.

On the whole, Marriott has gifted Indian academia with a framework that is rooted in Hindu substratum, the natural soul of India.

It has the potential not only to study Hindu society in a non-unidimensional manner while at the same time transform it towards more egalitarian and more harmonious state even as it undergoes the churning of post-colonial modernity.

Using his model and adapting it to the Dharmic and Advaitic reality that permeate India, is the best way to show gratitude to this soul that loved India all his life.