Politics

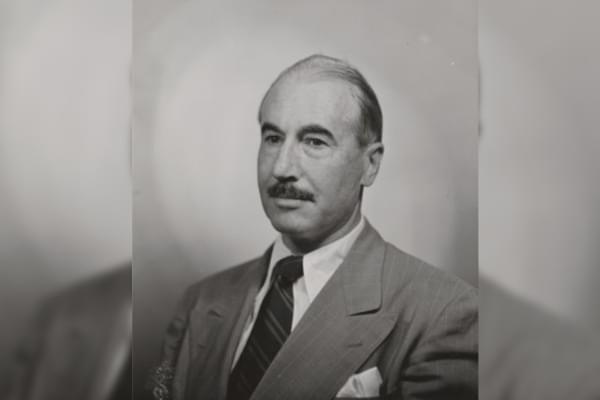

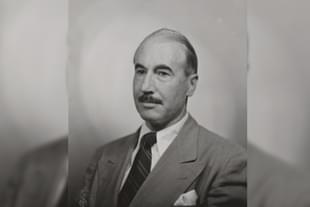

Walter Russell Crocker: Australian Diplomat And Newly-Discovered Icon Of 'North-South Divide'

Aravindan Neelakandan

Dec 11, 2023, 01:11 AM | Updated Dec 11, 2023, 08:31 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Following the Bharatiya Janata Party's (BJP) recent triumph in the Hindi-speaking states on 3 December, 2023, a narrative of a north-south political divide has emerged.

Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) MP Senthilkumar intensified this narrative by stating that BJP's success was limited to 'gaumutra (cow urine) states,' sparking renewed debates on India's cultural and political dynamics. As many have pointed out in online discussions, this was the same language as spoken by the Pulwama bomber.

Senthilkumar made his comment on 5 December. A day earlier, however, historian Ramachandra Guha waded into the same debate. He quoted a Western authority who also happened to be a Nehru-admirer and the third High Commissioner to India from Australia—Walter Russell Crocker (1902-2002).

âSouth India has counted for too little in the Indian Republic. This is a waste for India as well as an unfairness to south India, because the south has a superiority in certain important things â in its relative lack of violence, its lack of anti-Muslim intolerance, ... itsâ¦

— Ramachandra Guha (@Ram_Guha) December 4, 2023

Crocker was a high-ranking official of the British Colonial Services who first served in Nigeria and was later posted as High Commissioner in independent India.

Crocker serves as a notable example, illustrating the evolution of colonial thought, even as countries began to gain independence from colonialism. Remarkably, this shift in thought occurred while retaining colonial values.

The quote in the tweet itself is from Crocker’s biography of Nehru, Nehru: A Contemporary's Estimate, written mostly from an admiring perspective and published two years after Nehru passed away.

Prof. Kama Maclean, Historian of South Asian and World History at the University of New South Wales, makes the following observation with respect to this work of Crocker:

In 1964, Crocker wrote a biography of Nehru, demonstrating an appreciable understanding and warm admiration of him. Yet a reading of this book alongside Crocker’s other writings indicates that Crocker saw Nehru as quite exceptional. Scholars of Australian diplomacy note that Crocker felt Indians were oversensitive to racial discrimination, and... Crocker’s own dispatches as High Commissioner were on occasion ‘tinged with racist stereotypes’.Kama Maclean, 'British India, White Australia', University of New South Wales Press, 2020, p.232

During the Bengal Famine as well as the ‘Quit India’ Movement Crocker was very much in India. In fact, during the famine he was a part of the British war machinery that was directly overseeing operations in Bengal.

In 1946, he viewed with disdain the massive Indian support for INA soldiers during their trial and observed that ‘nationalism was rampant and it had become insane’.

Prof. Maclean points out another insight with respect to Crocker. For Crocker, ‘Indian opposition to racial restriction is to be seen as an extension of their caste-based perception [that] predisposes them to imagine comparable caste restrictions being imposed against them by the white races rather than a product of their experiences of colonialism.’ (Maclean, p.233)

Now let us come to the passage that Guha has quoted in his tweet. There is reason to believe that Crocker was not just an admirer of southern India but very specifically of southern Indian Brahmin culture. So when he refers to 'South Indian' he is likely referring to Brahmins of southern India.

The introductory pages of the book leading to the passage quoted by Guha should clarify this:

There is surely no group in the world with more intellectual capacity than the South Indian Brahman. Further, many of them are capable, in spite of nationalistic aberrations, of considering the other side.‘Nehru: a contemporary's estimate, 1966, pp. 44-5

Crocker then proceeds to criticize Indians for their sensitivity to treatment based on skin colour. He highlights that the only other group consistently expressing similar concerns about colour-based treatment is 'the American negroes.' Notably, Crocker asserts that 'South Indians' and Brahmins, particularly South Indian Brahmins, do not share this sensitivity.

It is difficult to make clear to those who do not know India from within how obsessive is the preoccupation with colour. The only other group which can compare with Indians in this respect are the American negroes. Not all Indians have it. South Indians for instance have much less of it than North Indians. Brahmans have less of it than other castes; South Indian Brahmans have little or none of it.ibid., pp.48-9

It is through these views of Crocker that one has to arrive at the quote on southern India that Guha quoted in his tweet.

Let us now go to that quote itself in its entirety:

As for the bridge, Rajaji could have been the bridge between South India and North India. South India has counted for too little in the Indian Republic. This is a waste for India as well as an unfairness to South India, because the South has a superiority in certain important things—in its relative lack of violence, its lack of anti-Muslim intolerance, its lack of indiscipline and delinquency in the Universities; in its better educational standards, its better government, and its cleanliness; in its far lesser practice of corruption and its little taste for Hindu revivalism.ibid., p.161

But the superiority that Crocker talks about was a relative advantage accruing to pre-Dravidianist southern India. This was due to the perception that compared to other regions of the country, the south had contributed lesser to the freedom movement. In fact, Guha could have done well to quote Dr Ambedkar who had pointed out such a divide between northern and southern India, in his treatise on linguistic states.

Southern India did not have a collective uprising like in the north in 1857. The south of India produced illustrious freedom fighters no doubt. But northern India suffered more under colonialism. That is a historical fact. Southern India is prosperous because the north paid a heavy price. In the final analysis, northern India sacrificed more for India's freedom, and that is a fact for which, this writer, as a proud Indian from the south, thanks the north.

Then the question: why did a scholar like Guha tweet a passage that invokes the alleged disunity between northern and southern India?

Here one needs to go into a deeper malady.

Nehru, whatever his faults and shortcomings, entirely agreed upon the indivisibility and cultural unity of India, but neo-Nehruvianism doesn't.

If only Guha would have turned to the very next page of Crocker's book, he would have found this passage there:

Rajaji saw himself as standing for the religious view. He believed that, to quote his own words, there is a greater Reality behind the sense reality and that spirit is immortal. He feared that this was being lost sight of under Nehru’s Government. He feared, too, the loss of freedom. But Nehru, too, respected the world of spirit; and, as well, he wanted freedom though he thought freedom was meaningless if men were hungry. The synthesis, not unattainable, surely, was never produced between these two freedom-loving and spiritual men.ibid., p.162

After Nehru, as Indira Gandhi leaned towards Dravidian and Communist elements, it's worth noting the significant role the South played in forging a democratic alternative to the Indira-Congress hegemon. Congress(O) under Kamaraj, Swatantra Party under Rajaji, and Jan Sangh formed a grand alliance that was both pan-Indian and aligned with the foundational ethics and civilizational wisdom of Bharat. This alliance, later instrumental in saving India during the dark days of Emergency, is a legacy continued by Modi in ways more than one.

Neo-Nehruvianism, distinct from the ideas of Nehru but with some clear connections employs a colonial-style civilizational scale. Here, disdain for Indian culture and alignment with colonial, Protestant-like ethics are seen as markers of civilization. Just as imperialism benefited England economically, Neo-Nehruvianism, in terms of power dynamics, benefits a specific dynasty. In this worldview, the Nehru-Gandhis are considered essential for India's identity and those opposing them are viewed as less civilized.

Dravidianism is a natural ally of this thought. Both do not accept the cultural and spiritual unity of India, and in this, neo-Nehruvianism is different from the ideas of Nehru himself.

However, Nehru is not entirely blameless. Crocker says that he heard a family member of Nehru talk with disdain about the 'tomfoolery of Hinduism' (p.30) and states that Motilal Nehru was 'contemptuous of religion in general and of Hinduism in particular.' (p.60) Later, Crocker provides a list of things Nehru was prejudiced against: '—Maharajas, Portugal, Money-lenders, certain American ways, Hinduism, the whites in Africa ... ' (p.138)

In a way, the fulminations of Dravidianists are less dangerous only because they are obvious. The perspective of Guha is more concerning because in that case a scholarly facade conceals what the DMK MP said openly in Parliament.