Culture

Reclaiming Onam: Understanding Mahabali's Return Beyond The Aryan-Dravidian Myth

Aravindan Neelakandan

Sep 05, 2025, 12:56 PM | Updated 12:59 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Every year, as the monsoons recede, the land of Kerala in Southern India erupts into a symphony of colour, flavour, and joy. The festival of Onam is a spectacle of profound cultural unity and abundance, predicated on a belief as beautiful as it is poignant: the annual return of the beloved, righteous king Mahabali from his subterranean kingdom to visit the people he once ruled.

The air is thick with the scent of marigolds and jasmine meticulously arranged into intricate floral carpets, or Pookalams, and the promise of the Onasadya, a harvest feast of such legendary variety that a local saying insists it must be eaten even if one has to sell their property to do so.

Yet, beneath this vibrant celebration of an idealised past, a modern shadow has fallen. A narrative that is simplistic and corrosive has gained ground. In this telling, the story of Mahabali and Vamana is stripped of its spiritual grandeur and recast as a crude historical allegory: the subjugation of a noble, indigenous Dravidian king (Mahabali) by the cunning trickery of an invading, fair-skinned Aryan Brahmin midget (Vishnu in His Vamana avatar).

This interpretation, which frames one of India’s deepest spiritual revelations as a mere record of ethnic conflict, is not only a gross distortion but a tragic theft. It robs the Puranic telling of its universal power and reduces a timeless map for the evolution of the human soul into a divisive political pamphlet.

When the anachronistic colonial lens is relinquished and understanding is sought through Indic interpretive traditions, brilliantly illuminated by modern seers like Sri Aurobindo, the Puranic Vamana Avatar may yield timeless insights that can guide one's own spiritual and psychological evolution.

Mahabali: The Peril of External Perfection

Mahabali as Asura is not a simplistic villain but a figure of immense stature and virtue. The Puranic accounts describe his rule as a golden age of unparalleled prosperity, justice, and harmony, where his subjects knew no poverty or sorrow. He is powerful, pious, and, above all, generous.

His kingdom thus becomes a testament to the highest possible attainment of the vital-mental man: a world of perfect ethical order, material abundance, and intellectual control. Yet this has a limitation. Its expansion is outward.

From the perspective of Jungian psychology, the character of King Bali presents a classic and highly sophisticated case of ego inflation. Ego inflation, in the Jungian model, is a state where the conscious ego identifies itself with the entire psyche, becoming overgrown and dominant, and losing its vital connection to the unconscious and the Self, the true centre of the personality.

An understanding of Mahabali from a Sri Aurobindonian perspective reveals the King as being composed of the physical, vital, and mental planes of existence, the domains of material reality, life-energy, and intellectual thought. Where Jungian psychology may show the surface as just ego, Sri Aurobindonian analysis shows further elements, both structural and functional, in the Puranic episode.

Through immense effort, penance, and the performance of one hundred Ashwamedha sacrifices, Bali has achieved total control over the lower planes of the psyche. His power, wealth, fame, and even his strict adherence to dharma, his unshakeable commitment to his word, represent the highest possible attainment of the vital-mental man.

The Crisis

For a Jungian psychologist, a person in the place of Mahabali is precisely diagnosed as a "noble ego inflation". This is not the crude inflation of a tyrant, but a far more subtle and dangerous condition.

Bali's ego has become fused with admirable, archetypal qualities: the Benevolent King, the ultimate Giver. This identification leads his ego to believe it is the centre and source of these virtues, cutting it off from the deeper, transpersonal Self which is the true source of all such qualities.

The result is a deeply felt deficiency despite all virtues. The result is the Yajna made to conquer all the worlds, external worlds, the Viswajit sacrifice.

Herein lies the Purana’s profound psychological genius. The greatest obstacle to complete integration is not Bali's vice, but his very virtue. A perfected, self-satisfied system is, by its nature, resistant to the call for transcendence because it has anchored all the good emanating from the deeper Self to the egoistic self. The result is that at any moment he could become a world-conquering typical Asura.

The Strategic Humility of Vamana

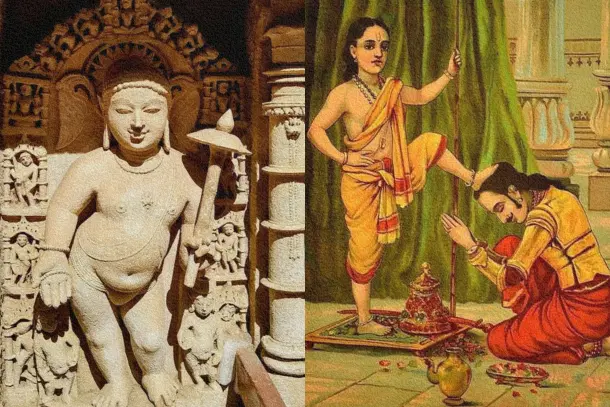

The Divine, required to break this impasse and the possibility of a tragic fall, arrives not with cosmic thunder but in a form of profound and strategic humility. Vamana appears as a small, seemingly insignificant Brahmin boy, a dwarf, whose request is almost absurdly small: "three paces of land".

This juxtaposition is not an incidental detail; it is a spiritual necessity. From a Sri Aurobindonian viewpoint, Vamana's dwarf form is the perfect symbol of the indwelling consciousness. The Katha Upanishad makes Yama, a great king, tell a Brahmin boy Nachiketa that "the Purusha, of the size of a thumb, dwells in the body" (aṅguṣṭhamātraḥ puruṣo 2.1.12).

In the Upanishad the Brahmin boy asked Yama, who promised to give everything, nothing but the knowledge of the Self. Here, to the great king Mahabali, Vamana the Divine in dwarf form asked for three feet of land.

Shukracharya: Shadow Archetype and Archetypal Temptation

The pivotal scene where Bali's preceptor, the sage Shukracharya, warns him that the dwarf Brahmin is Vishnu in disguise and begs him to retract his promise, is in a way an equivalent of Yama asking Nachiketa to deviate from his own purpose. There it is the promise of future wealth and power. Here it is the loss of present wealth and power.

Shukracharya functions as an archetypal shadow, the shadow of the Wise Old Man archetype, bringing out a truth which can lead the self away from its highest Truth. A lesser truth is weaponised against the Truth by a shadow archetype. In fact, the Purana here provides a more analytical tool to understand the psyche than Jungian psychology.

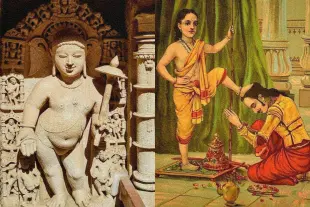

Bali's response is telling. He does not engage with the substance of the warning but instead dismisses it by appealing to his own virtuous self-image. He is the grandson of Prahlada, he has made a promise, and he cannot go back on his word for the mere "greed of wealth".

Adhering to the principle here becomes more important than the fear of losing the external multipliers of ego. This adherence becomes his pathway to his deliverance.

Cosmic Form of Three Strides

Once Bali sanctifies his promise, the drama’s central transformation occurs. The small Vamana expands into his gargantuan cosmic form, Trivikrama, the Lord of the Three Strides.

With his first stride, He covers the entire Earth. With His second, He encompasses the heavens and the mid-region. In short, with His two strides He has shown the entire universe as being that of the Divine.

This is not an act of clever trickery, but of profound ontological revelation. Trivikrama does not simply take the world from Bali; He reveals that the world was never truly Bali's to possess in the first place.

When this understanding dawns, it becomes clear that through renunciation the real enjoyment comes, and there is nothing to covet. (tena tyaktena bhuñjīthā mā gṛdhaḥ kasya sviddhanam — Isavasya Upanishad, verse 1).

Psychologically, this is the ego's sudden, overwhelming, and shattering confrontation with the true scale of the Self. The king who believed he was the master of the three worlds is confronted with a reality so immense that his entire kingdom is contained in just two of its strides. His ego reaches a total impasse; its framework of reality is irrevocably broken.

He is left standing in a void, stripped of all external reference points, face-to-face with an immeasurable divine cosmic reality.

This is the process of individuation which ultimately results in an evolutionary transformation.

The process of individuation often begins with a "wounding of the persona", an event or realisation that shatters the ego's inflated self-perception and forces it to confront its limitations. For Bali, this wounding occurs on a cosmic scale.

When Vamana expands into his universal form, Trivikrama, Bali's entire worldview collapses. The king who believed he was the master of the three worlds is confronted with a reality so immense that his entire kingdom is contained in just two of its strides. His ego reaches a total impasse; its framework of reality is irrevocably broken.

At this moment of crisis, the ego has a choice. It can react with defiance, clinging to its shattered sovereignty (as Bali's Asura followers attempt to do by attacking Vamana), or it can surrender to the greater, transpersonal reality that has been revealed.

This is also the sacrifice, the Yajna. This integrates the conscious (ego) with the Self. Bali's subsequent fate is not a punishment but the natural consequence of this integration.

The Transformation

Bali's choice to offer his head is the choice for individuation through total surrender. It is the conscious ego's recognition that it is not the centre of its psychic universe and its voluntary decision to subordinate itself to the true centre, the Self.

Instead of banishing him to a desolate hell, Vishnu granted Mahabali rulership over the realm of Sutala. This realm, specially constructed by the celestial architect Vishvakarma, is described as being free from all misery and more opulent and desirable than even Svarga, the heaven of the Devas.

The culmination of this divine exchange is the promise of protection, which is the scriptural basis for the "gatekeeper" tradition. In the Srimad Bhagavatam, Canto 8, Chapter 22, Verse 35, Vishnu declares to Mahabali.

His "rule" in Sutala signifies a profound shift in psychic orientation. He is no longer the king of the outer manifest world, the domain of the persona and the inflated ego, but becomes a ruler in a deeper realm of the psyche, now living in a proper relationship to the Self.

O great hero, I shall always be with you and give you protection in all respects, along with your associates and paraphernalia. Moreover, you will always be able to see Me there, situated nearby.

In popular retellings and derivative texts, this promise of perpetual guardianship by Vishnu to Mahabali in Sutala is explicitly articulated as Vishnu assuming the role of a gatekeeper or guard. That is hyperbole of Bhakti. But still it is in tune with the spirit of the Puranic episode.

This understanding of the Puranic language is the absolute prerequisite for understanding Onam.

Onam: The Return of the Holistic Rajah

The Mahabali who is welcomed back to Kerala is not a defeated king returning from exile. He is the archetype of the perfectly integrated being, the enlightened devotee returning as a blessing from his inner kingdom.

The celebration is not for the Asura who lost the three worlds, but for the self who gained the Divine.

This resolves the apparent contradiction of a largely Hindu populace celebrating a figure "vanquished" by an Avatar of Vishnu. The key rituals of Onam are a sophisticated cultural technology for making this abstract ideal of integrated consciousness experientially real each year.

The grand feast of the Onasadya is a form of communal eucharist, a ritual where the community does not just show prosperity but ingests and internalises the very essence of the ideal state.

The floral Pookalam is far more than a welcome mat; it is a temporary mandala, a sacred geometric design that consecrates a space to receive and ground the returning spiritual ideal.

The vibrant snake boat races, the Vallam Kali, are a channelled expression of the collective’s organised life-force, a ritual performance of the unified energy that defines the ideal kingdom.

In all these, Indian culture reiterates its conviction that spiritual liberation and material prosperity need not be diametrically opposite. A wise King in his Sutala dwelling, and all is well in the world above.

To apply the Aryan-Dravidian binary to this magnificent psycho-spiritual drama is an act of profound ignorance. It flattens a multi-dimensional map of the soul into a one-dimensional political cartoon. It asks us to choose sides in a conflict that never existed, distracting us from the myth’s true and urgent invitation: to undertake the same journey as Bali.

The Purana endures because it renews itself through each one of us.

It reminds us that true growth is not an endless expansion of the ego's domain, however outwardly perfect it might be, but a re-alignment with a deeper centre. It teaches that this transformation requires a crisis, a humbling, and a courageous act of surrender to a reality far greater than our current conception of ourselves.

The image of the foot of the infinite placed upon the head of the finite is not an image of defeat, but the supreme symbol of initiation and grace. It is the moment the limited self yields to the boundless Self, and in doing so, is reborn into a vaster and more authentic existence.

The spiritual vision of this annual return and connected celebrations must be understood in the context of Mahabali's transformation.

His "return" is not the literal visit of a mythological figure from a physical netherworld. Rather, it is the annual, ritual-induced return of an ideal state of consciousness into the collective psyche of the community.

A rooted spiritual-psychological understanding of the Vamana-Mahabali Puranic episode through Indic and inner lenses and mapping those insights onto the festival's core rituals allows a holistic interpretation of Onam to emerge.

The festival is revealed to be far more than a harvest celebration or a nostalgic commemoration of a mythological king. It is a profound and functional cultural mechanism for collective psychological and spiritual renewal.

The enduring genius of Onam lies in its ability to translate a deep, complex, and universal allegory, the evolution of consciousness through the surrender of the perfected ego to the divine Self, into a set of accessible, engaging, and powerful community rituals.

The festival is the cultural mechanism used to make this abstract ideal immanent and tangible. As Mahabali now embodies the integrated Self in his inner kingdom of Sutala, his "visit" to the outer world of Kerala is best understood as an emanation of that perfected inner state.

This is the timeless truth at the heart of Onam, a truth we must reclaim from the divisive narratives of the present, for the sake of a more integrated future.