Economy

$25 Billion Within Reach: Can India’s Tools Sector Deliver?

Amit Mishra

May 08, 2025, 01:01 PM | Updated Jun 02, 2025, 11:33 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Some revolutions roar; others hum in the background.

India’s economic transformation has seen plenty of headline acts — IT parks in Hyderabad, chip fabs in Gujarat, solar farms in Rajasthan. But tucked away from the spotlight, in foundries and workshops from Ludhiana to Coimbatore, another revolution has been steadily shaping the backbone of Indian industry.

This is the story of the country’s hand and power tools sector — a low-key workhorse in a high-decibel economy. It doesn’t glitter like semiconductors or soar like software exports. It clangs, grinds, and drills — and in doing so, quietly powers the backbone of India’s industrial growth.

The men and women who make these tools don’t often find themselves in glossy brochures or policy speeches. Yet, without their output — the humble spanner, the reliable hammer, the buzzing cordless drill — the wheels of Indian industry would simply not turn.

A Market on the Move

Walk into a garage in rural India, and you’ll spot trusty, rust-resistant spanners and screwdrivers that have weathered decades. Visit a modern furniture studio in Gurugram or watch a Bengaluru-based YouTuber's DIY tutorial, and you’ll see sleek, battery-powered tools at work.

This juxtaposition defines India’s tools market — grounded in tradition, yet flirting with a tech-driven future.

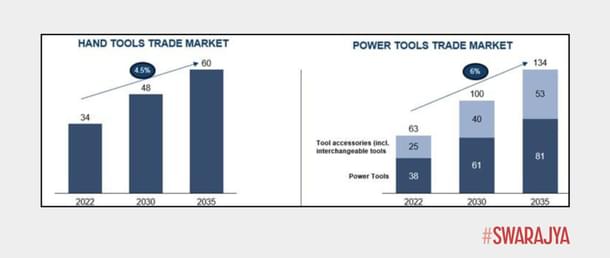

Globally, the hand and power tools industry stood at $100 billion in 2022 and is projected to hit $190 billion by 2035, growing at 5.3 per cent CAGR. Power tools are the growth engine here — already a $63 billion market, expected to more than double to $134 billion by 2035.

What’s powering this rise?

Power tools are seeing strong tailwinds — thanks to booming construction, rising consumer spending, and a growing DIY culture. Electric tools dominate this space, comprising 70 per cent of the segment with must-haves like angle grinders and rotary hammers.

Valued at $34 billion globally, hand tools grow at a steadier pace. They remain essential for precise work, rugged conditions, and budget-conscious markets — particularly relevant for India’s fragmented yet resilient MSME sector.

Two Industries, Two Playbooks

Behind the scenes, the machinery of global trade moves very differently for hand and power tools.

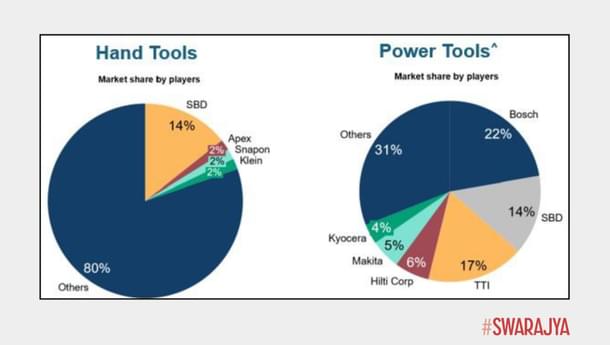

The hand tools supply chain is a sprawling patchwork. Production is widely distributed, with the top four players capturing just 20 per cent of global market share. It’s a game of many small players, each carving their niche. Apex Tool Group, for instance, manages 20 manufacturing plants spread across the US, Mexico, Germany, and Canada — sourcing steel bars, cobalt, and tungsten from a mosaic of local and international vendors.

This decentralization makes the industry resilient, but also harder to scale uniformly. It thrives on local knowledge, lower capital needs, and high labor intensity — tailor-made for India's small-scale manufacturing clusters.

Power tools, by contrast, are a tighter, more high-stakes affair. The top six companies dominate 70 per cent of the global market, and their operations reflect that consolidation.

Brands like Makita and Hilti run fewer, highly automated factories — seven and four countries respectively — and source materials like motors, batteries, electronics, and high-performance plastics from centralized suppliers. It's a space that demands big bets — in R&D, in automation, and in global distribution strategy.

For policymakers, this contrast calls for a dual strategy: support MSME clusters and local sourcing for hand tools; enable tech partnerships, export incentives, and anchor investments for power tools.

Where Does India Stand in the Global Tools Trade?

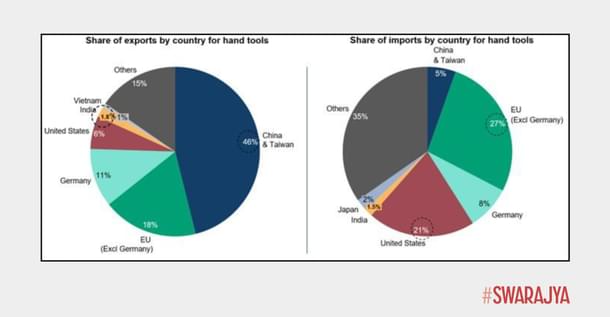

The global tools trade is a colossal $100 billion industry, with China and the European Union (excluding Germany) reigning supreme as the largest exporters.

Together, China and Taiwan dominate the field—commanding a staggering 46 per cent share in hand tools exports and 37 per cent in power tools. Meanwhile, the EU bloc (minus Germany) adds significant weight with an 18 per cent and 22 per cent share, respectively.

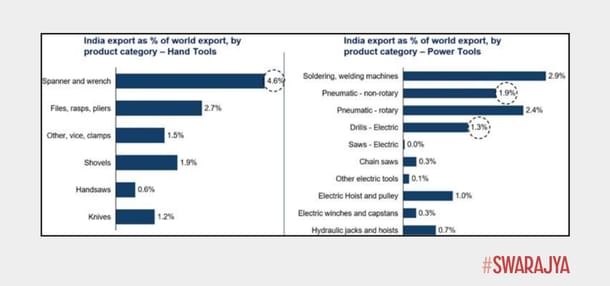

India, however, remains a minor player on the world stage—contributing a modest 1.8 per cent to global hand tools exports and just 0.7 per cent to power tools. This disparity not only reflects India's underrepresentation but also hints at a vast, untapped opportunity waiting to be seized.

But the devil is in the details. India’s export performance swings wildly across product categories. In hand tools, the country punches above its weight in some niches—accounting for 5 per cent of global spanner and wrench exports—yet barely makes a dent in others, like handsaws, where its share falls below 1 per cent.

The story is similar in power tools: India holds a small but respectable 2 per cent slice of the pneumatic tools pie, yet electric tools like drills and saws remain largely foreign territory.

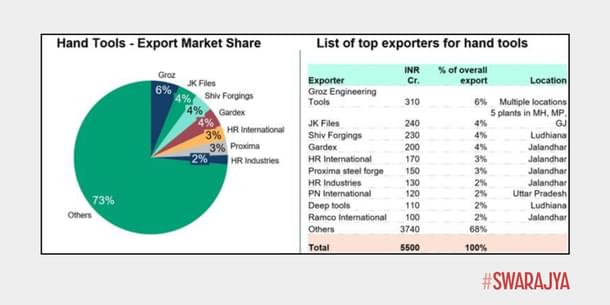

India’s strength lies in the hand tools segment—thanks to its labor-intensive nature and lower technical entry barriers. This edge has given rise to a bustling ecosystem powered by MSMEs. Industry stalwarts like Groz Engineering, JK Files, Shiv Forgings, Gardex, and HR International lead the charge, with the top seven exporters alone accounting for nearly 25 per cent of India’s total hand tool exports.

Geographically, India’s hand tools manufacturing is clustered in just a few powerhouse regions—primarily Jalandhar and Ludhiana in Punjab, along with industrial belts in Mumbai, Nagpur (Maharashtra), and Nagaur (Rajasthan). Punjab alone dominates the landscape, churning out a whopping 80 per cent of India’s hand tool exports. In fact, 12 of the country’s top 15 hand tool companies call Jalandhar and Ludhiana home.

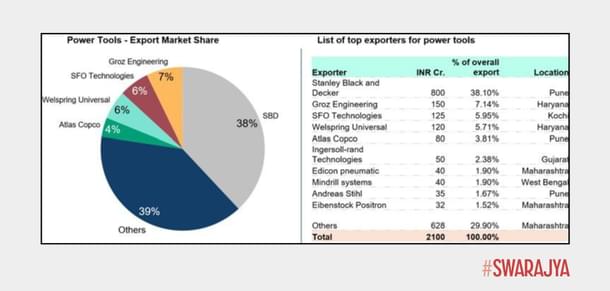

On the flip side, India’s power tools industry is still in its infancy compared to the hand tools sector. While major players like Stanley Black & Decker and Groz Engineering hold a combined 45 per cent share, the sector lacks depth. Global heavyweights such as Hilti, TTI, and Makita have yet to build a robust manufacturing footprint in the country.

Yet, change is on the horizon. As sectors like automotive, aerospace, heavy engineering, and infrastructure heat up, the demand for high-precision power tools—drills, grinders, cutters—is steadily rising. This surge presents a golden opportunity for India to ramp up local production, attract global investment, and transform its power tools landscape.

The Sore point

India, with its storied tradition in hand tools and a nascent but promising power tools industry, ought to be a global heavyweight by now. The aspiration to capture 25 per cent of the world’s hand tools market and a solid 10 per cent of power tools is not a reach—it’s a rightful goal, long overdue. And yet, the path to that summit is strewn with bottlenecks: structural, systemic, and strategic.

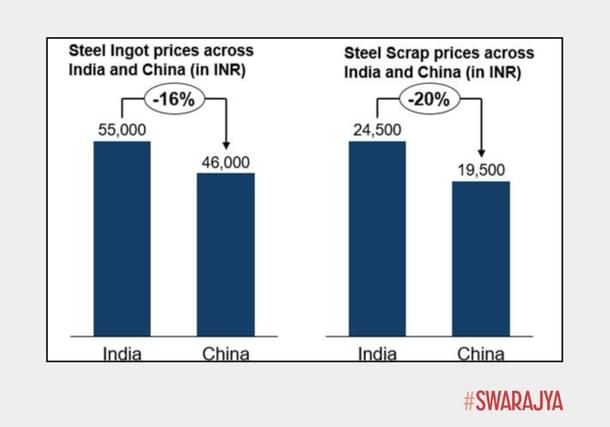

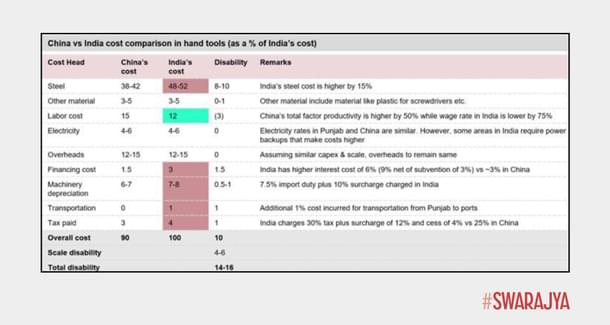

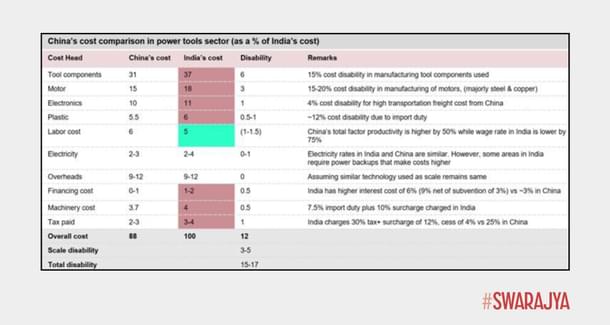

At the heart of the problem lies an uncomfortable truth—India is not cost-competitive. The average Indian manufacturer is routinely undercut by Chinese counterparts, a consequence of both intrinsic and extrinsic disadvantages.

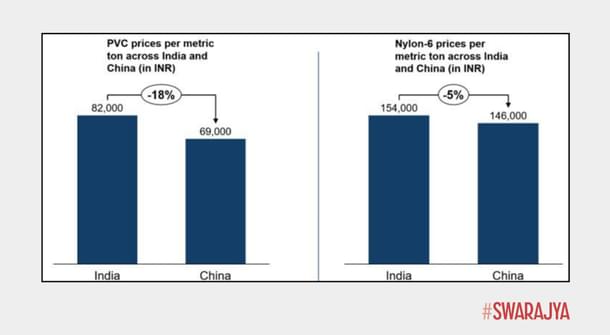

Take steel ingots, the lifeblood of hand tool production—they cost 16–20 per cent more in India. In the power tools domain, the pattern persists: motors are dearer by 10–15 per cent, electronic components command a 5 per cent premium, and engineering plastics like Nylon-6 and PVC sit far above global price points.

This material inflation is exacerbated by a policy environment that leans heavily on protectionism. Import duties—15 per cent on steel, up to 15 per cent on motors, and nearly 10 per cent on PVC—form a high tariff wall that stifles competitive sourcing.

Overlaying this is a regime of quality control restrictions that, while intended to safeguard standards, inadvertently stifle competitiveness. Since India imports more than half of its PVC and virtually all its Nylon-6, the manufacturing ecosystem is precariously dependent on costly foreign inputs, further widening the cost chasm.

What magnifies this disadvantage is India's chronic under-scale. While China leverages massive production volumes to dilute costs, Indian manufacturers—fragmented and modest in scale—are unable to enjoy the same economies. The per-unit cost of production, consequently, is higher, rendering Indian tools less price-competitive in global markets.

In short, India suffers not only from a factor cost disability but also from a scale disability—each reinforcing the other in a feedback loop of inefficiency.

And the frictions don’t end there.

Labour, though inexpensive in absolute terms, is encumbered by rigid regulations that restrict flexibility and productivity. Overtime is not only capped but also paid at a steep premium, and stringent limits on daily and weekly work hours dilute operational efficiency.

Logistics add another layer of cost and complexity. Punjab, a major production hub, is landlocked; every consignment must make an overland journey to distant ports like Mundra, pushing up Freight on Board values by 1 to 1.5 percent.

Energy—a silent but critical input—also fails to cooperate. Frequent power cuts necessitate the use of captive generators, which drive up electricity costs to nearly double the grid rate. The prospect of transitioning to solar power is undermined by restrictive net metering regulations, such as Punjab’s 90 percent cap on solar contribution, which curtails long-term savings for manufacturers.

Finance, a key enabler of industrial growth, is another Achilles’ heel. With interest rates hovering 3 per cent higher than competing economies, India’s capital cost is prohibitively steep.

Meanwhile, the very machinery that Indian manufacturers require to modernize—CNC systems and high-precision equipment—must be imported, incurring duties and surcharges that inflate acquisition costs by over 17 percent.

Government schemes like EPCG, though theoretically beneficial, are mired in complexity and discourage participation, especially among small and medium enterprises. Many manufacturers, wary of fluctuating markets and burdensome obligations, simply opt out.

Taxation, too, adds its own drag. At an effective rate of 34 percent, Indian manufacturers pay more than their Chinese (25 per cent) and Vietnamese (20 per cent) counterparts. Worse, while China rewards innovation with generous R&D tax deductions and accelerated depreciation, India has rolled back such incentives, dulling the very edge it needs to sharpen.

But perhaps the most telling gap lies in capability. India can produce standard tools—but when it comes to high-precision components, it still leans heavily on imports.

Consider the humble ratchet spanner: while it is assembled in India, the ratchet mechanism—a crucial and high-value component—is often imported from China, accounting for nearly a third of the product’s value. A lack of indigenous technical know-how, weak R&D infrastructure, and limited reverse engineering capacity have left India stuck in the low-value end of the tools spectrum.

Even land—the most fundamental industrial input—is in short supply or overpriced. Around Ludhiana and Jalandhar, land prices run as high as ₹3–5 crore per acre. Where land is available, restrictive floor space ratios—1.1 in Pune, compared to 2.5 to 9.5 in cities like Hong Kong—throttle expansion before it begins.

In sum, India has the pedigree, the potential, and the people. What it lacks is a conducive ecosystem. Cost structures are skewed. Policy incentives are patchy. Scale is elusive. Innovation remains timid.

The Opening India Must Seize

The world is at an inflection point. Countries are urgently seeking to diversify their sourcing away from China—a movement accelerated by tariffs imposed by the US and a broader desire for supply chain resilience.

These shifts have tilted the scales, creating fertile ground for India to emerge as a powerful alternative. But the clock is ticking.

Vietnam has already moved with quiet determination, tripling its tool exports since 2019. Chinese firms, wary of growing geopolitical friction and wary of sanctions, are diversifying rapidly into Southeast Asia. The race is well underway—and for India to seize its rightful place, it must act with urgency and intent.

The good news is: India does not begin from a blank slate.

A strong hand tools industry already exists, anchored by a network of MSMEs that have honed their craft over decades. These enterprises bring not only agility and employment but also a grassroots culture of innovation. Their foundations are solid—and ready to be scaled.

What gives India a distinct edge is its natural advantages, beginning with labour. In hand tools manufacturing, labour accounts for about 15 per cent of the total cost—and here, India is remarkably competitive. With wages averaging just $1 an hour, compared to China’s $3.50, India holds a compelling cost advantage that few nations can rival.

But cost is only one side of the story.

India’s industrial depth, shaped in large part by its automotive sector, is equally powerful. Processes like forging, stamping, and casting—essential to both car parts and hand tools—are already deeply embedded in the country’s manufacturing landscape. This overlap allows for seamless expansion, shared infrastructure, and accelerated scaling.

Then there is the matter of quality.

Indian hand tools are not just affordable—they are credible. Products like spanners and wrenches manufactured in India already meet international standards and find steady demand across Europe and beyond. Today, India commands about 5 per cent of global trade in these tools—a quiet but firm proof of its capability.

Put together, these elements—competitive cost, industrial synergy, and global trust—form a potent base from which India can rise, not just as an alternative to China, but as a leader in its own right.

Yet, the journey is not without its hurdles.

While hand tools offer a strong foundation, the power tools segment presents a steeper climb. This space is far more dependent on a sophisticated electronics ecosystem—particularly for components like motors, controllers, and battery packs. And in this domain, India is still finding its footing.

Consider the example of Bosch, which produced 17 million power tools and batteries in Malaysia back in 2018. India’s current output, by contrast, lingers around just 2 million units—a stark indicator of the gap that needs bridging.

But change is already afoot.

Government initiatives like Make in India and the Production-Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme are beginning to direct capital and attention toward electronics manufacturing, battery technology, and precision engineering. With the right policy push, targeted investment, and sustained execution, India can build the ecosystem it currently lacks.

The Road Ahead

The hand and power tools sector may never have the glamour of tech startups or the media presence of electric mobility. But it doesn’t need it. Its success lies in something more enduring — utility. As India builds, fixes, renovates, and manufactures its future, tools will remain the quiet constant in the background.

But to unlock the sector’s full potential, India will need to make a few critical bets.

The NITI Aayog’s report on “Unlocking $25+ Billion Exports: India’s Hand & Power Tools Sector lays out a bold, pragmatic roadmap to elevate India to the top ranks of the global hand and power tools market.

Anchored in deep structural analysis, the the strategy focuses on three key pillars: developing world-class manufacturing clusters, undertaking sweeping structural reforms, and deploying transitional support mechanisms to overcome the cost challenges the sector currently faces.

At the core of this transformation is the creation of integrated, globally benchmarked manufacturing clusters specifically designed for the hand tools sector. The vision is to establish three to four such clusters by 2035, covering approximately 4,000 acres, with at least one of them in Punjab, India’s traditional heartland for hand tool production.

The aim is to create plug-and-play infrastructure, modern housing for workers, advanced R&D and testing facilities, effluent treatment plants, and convention spaces. These clusters will provide assured access to water and electricity, making them ideal for large-scale industrial activities.

A capital investment of Rs 12,000 crores is earmarked for the development of these zones, and industry players are expected to invest an additional Rs 45,000 crores over the next decade to support operations, build capacity, and expand within these zones.

But infrastructure alone won’t be enough. To truly compete on the global stage, India must address the cost disparity it faces—currently a 14-17 per cent disadvantage compared to China. Structural reforms across several critical areas are needed to level the playing field. This includes reducing import duties on essential materials like steel, motors, and PVC, and rationalizing the Quality Control Orders that currently complicate the manufacturing process.

India must also modernize its labor laws, making working hours and overtime compensation more flexible and globally competitive. Similarly, capital goods and export promotion schemes need to be updated, with simplifications in the EPCG scheme and reductions in duties on imported machinery.

Energy and logistics are two other areas that require urgent attention. Providing uninterrupted, 24/7 power within industrial clusters will help eliminate the need for costly captive power, which is currently as much as Rs 18 per unit, compared to Rs 7–8 from the grid. Logistical inefficiencies, particularly in landlocked hubs like Punjab, also need to be addressed to reduce freight costs and improve competitiveness.

Additionally, India’s land-use policies need to be liberalized. Simplifying norms around Floor Area Ratio, ground coverage, and green space will make industrial plots more affordable and efficient.

Lastly, India must facilitate global technology transfers by easing visa norms and simplifying import procedures, while also prioritizing domestic R&D to fuel innovation.

In the event that such structural reforms face delays in implementation, the report recommends a calibrated bridge support mechanism to help Indian manufacturers remain globally competitive in the interim.

The question isn’t whether India can lead in tools — it’s whether it chooses to. The fundamentals are in place. The ambition is palpable. What remains is execution: aligning policy with potential, incentives with impact.

Do that, and India won’t just supply tools to the world. It will reshape how the world works — one ratchet, one revolution at a time.