Obit

S L Bhyrappa: A Life Etched In Truth

Shefali Vaidya

Sep 24, 2025, 06:27 PM | Updated 06:27 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

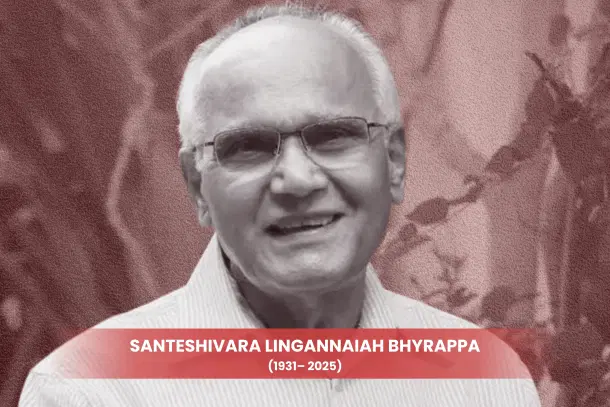

There are moments in history when immortal words outlast the mortal body. The passing of Santeshivara Lingannaiah Bhyrappa on 24 September 2025 is one such moment. S. L. Bhyrappa leaves behind not just a literary legacy but a smorgasbord of ideas, questions, and uncompromising truths.

For me, as for countless other readers of his original Kannada novels as well as their translations, his death feels like a deeply personal loss. I was introduced to his works through the excellent Marathi translations by Uma Kulkarni. The first novel I read was Aavarana, and it affected me like very few works of literature have. After that, I devoured Saartha, Mandra, Tantu, and his magnum opus on the Mahabharata, Parva, in rapid succession through Uma Kulkarni’s translations. I was blown away by his vast repertoire, depth of research, and attention to detail.

Troubled Childhood

Reading his autobiography Bhitti and his semi-autobiographical novel Grihabhanga was a searing experience. Bhyrappa’s story began in the dusty lanes of Santeshivara, a small village in present-day Hassan district of Karnataka. He was born in 1931 into a traditional family of hereditary village accountants.

Life, however, dealt the young Bhyrappa more than his fair share of tragedy. Plague snatched away his mother and elder brother when he was still a child. He was denied even the final glimpse of his mother’s face, a wound that never healed.

His father, eccentric and irresponsible, did little to shield him from hardship. The responsibility of accounts and household management had already fallen on his mother’s shoulders before death claimed her. After her passing, the young Bhyrappa became a wanderer of circumstance. He was sent to live with his maternal uncle, but instead of providing care, the uncle inflicted cruel mental and physical torment. The boy was pushed into adulthood too soon, carrying burdens no child should bear.

Education was his only escape, and yet even that came at a terrible price. He had to toil while studying: living in orphanages, eating at charity homes, selling incense sticks, cooking in small eateries, doing hard manual labour at railway stations. For a few months he lived with itinerant sadhus, roaming from place to place, absorbing the rhythms of ascetic life. At one point, he even worked as a porter at Mumbai railway station.

Yet Bhyrappa never gave up. Propelled by sheer willpower, he not only completed his education but excelled at it. He graduated from Mysore University with a gold medal in Philosophy, later completing his Ph.D. on Satya Mattu Soundarya — Truth and Beauty. This thesis on aesthetics formed the foundation of his literary edifice. His entire literary career, indeed his entire life, was a long meditation on those two concepts: truth and beauty.

The Teacher and the Thinker

Before he became a household name as a Kannada novelist, Bhyrappa was a teacher. He taught in Karnataka, then at NCERT in Delhi, and later at universities in Gujarat. Teaching, for him, was not merely a profession; it was part of his philosophical quest. He believed that the transmission of knowledge was sacred. It was perhaps this grounding that later gave his novels their unshakable moral centre. His classrooms may have been filled with students of philosophy, but the world became his larger classroom, and his readers, his lifelong students.

The Novelist of Ideas

When Bhyrappa turned to fiction, he did not treat it as entertainment. A Bhyrappa novel was never a conventional story with conflict and resolution. It was an intellectual excavation, a spiritual enquiry, a psychological journey. He once said that he wrote only after years of research, that he could not invent until he had understood. This integrity shows in every one of his twenty-four novels.

Take Vamshavriksha (The Family Tree), which won him the Kannada Sahitya Akademi Award in 1966. It explored generational conflict and the weight of tradition versus personal freedom. The novel was later adapted into an acclaimed Kannada film.

Then there was Parva, his magnum opus on the Mahabharata. Here he stripped away divine halos and presented the epic as a profoundly human saga. Warriors were not demigods but men with doubts, desires, and flaws. Reading Parva is to be jolted into seeing the Mahabharata anew, to realise that the questions of dharma, power, loyalty, and morality are eternal.

Mandra explored the world of Indian classical music, delving into the raga of life itself. Tantu mirrored the decline of values during the Emergency years. Saartha was a philosophical caravan into India’s past, weaving history with imagination.

And then came Aavarana, perhaps his most controversial work. On the surface, it was the story of a Hindu woman, Lakshmi, who marries a Muslim man, becomes Razia, and slowly awakens to the truth of religious fundamentalism. But at a deeper level, it was Bhyrappa’s audacious attempt to confront the historical wounds inflicted by Islamic invasions on India’s civilisational soul. The book caused a storm. Critics accused him of bigotry, but his readers hailed him as fearless, as a voice that dared to articulate what had been suppressed.

What struck me most about Aavarana was not its polemic but its raw honesty. Bhyrappa did not hide behind academic jargon or ideological hedges. He wrote what his research revealed, what his conscience compelled. I disagreed with the optimistic ending of Aavarana, where the bigoted husband suddenly has a change of heart. When I met Bhyrappa in person at the Mangaluru Literature Festival, I mustered all my courage and shared my disagreement with him.

I fully expected him to be offended. Instead, he listened quietly, smiled, and said, “Perhaps I was too optimistic back then. Perhaps I wanted to end on the positive note of reconciliation.” I was pleasantly surprised by his humility. What other writer of his stature would grant a mere reader that dignity?

The Eternal Outsider

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Bhyrappa never joined literary cliques. He stood apart from the fashions of the day. The Navya school of Kannada literature, with its experimental modernism, tried to claim the literary throne; the Bandaya movement thundered with slogans of protest; later, Dalit literature rose with its searing indictments. But Bhyrappa belonged to none.

He was too disciplined, too solitary, too devoted to truth to be bound by any ism. This independence earned him both admiration and hostility. He was criticised, vilified, even ostracised by sections of the literary establishment. Yet he continued to write, undeterred, driven only by the demands of his inner voice.

This refusal to compromise, to curry favour, is why his readers loved him so deeply. Awards came: the Saraswati Samman in 2010, the Sahitya Akademi Fellowship in 2015, the Padma Shri in 2016, and the Padma Bhushan in 2023. But long before these official honours, Bhyrappa had already won the accolades of readers’ hearts. His books were sold out even before the first edition was in the market.

Bhyrappa’s readers belonged to all socio-economic classes. At the Bhyrappa Sahitya Mahotsava organised in Mysuru in 2019, his readers travelled from far and wide to meet their favourite author. One of them was a barber in a small shop in rural Karnataka who had travelled for 12 hours, changing three buses, just to take Bhyrappa’s autograph.

Women of Flesh and Fire

One of the most striking features of Bhyrappa’s novels is his portrayal of women. His women characters are not silent sufferers or one-dimensional victims. They are complex, resilient, layered human beings.

Nanjamma in Grihabhanga, based on his own mother, is a case in point. Born into poverty, trapped in a cruel marriage, tormented by an abusive mother-in-law, she still refuses to surrender her humanity. She fights for her children, clings to her dignity, endures, and survives. In her struggle, we glimpse the struggle of countless unsung women of rural India.

Or think of Draupadi in Parva. Stripped of divinity, she emerges as a woman of burning pride, sensuality, anger, and anguish. She is no longer a divine legend; she is a woman of flesh and blood like us.

Bhyrappa’s women endure unimaginable trials but rarely lose their core. They may be scarred, but they are never broken. Reading them is to confront the quiet heroism of Indian womanhood.

Integrity Above All

Bhyrappa’s quest for truth did not come cheap. His books stirred many storms. Aavarana was accused of being communal. Tantu was said to be too political. His frank views on history, religion, and culture often clashed with the dominant leftist narrative.

But controversy did not define Bhyrappa. His integrity did. He once told me in an interview, “A writer must be loyal only to truth, not to ideology, not to popularity.” That credo guided him throughout his career. In an age where many writers bent with the winds of political correctness, Bhyrappa stood like a tall banyan tree, battered by storms perhaps, but never uprooted.

Despite his larger-than-life stature, Bhyrappa was a simple man of few words and needs. When I met him in person, I expected him to be a little arrogant. After all, here was a man whose books had sold more than half a million copies, who had been translated into every major Indian language, who was hailed as Karnataka’s greatest living novelist.

In reality, Bhyrappa was soft-spoken, almost shy, yet with a piercing gaze that seemed to look right through you. When he spoke, he weighed words as if they were gold coins. When he listened, he gave you the full dignity of his attention.

When I timidly told him that I did not agree with the ending of Aavarana, he did not dismiss me. He did not patronise me. He absorbed my critique, reflected, and conceded. That day, I learnt a profound lesson: greatness is not measured by how loudly one proclaims, but by how humbly one receives.

Legacy

What is S. L. Bhyrappa’s legacy?

It is not just his twenty-four novels, though each is a monument in its own right. It is not just his awards, though they glitter in the annals of Indian literature. His true legacy is the generations of minds he nurtured and awakened.

Bhyrappa taught us that literature is not mere storytelling. It is a searchlight into history, philosophy, music, politics, and the human heart. He taught us that to write is to risk, to offend, to question, to bleed. He taught us that the writer’s first duty is to truth, even if truth is uncomfortable.

For the common reader in Karnataka, he was not a distant icon but an intimate presence. His books were read in homes, discussed in village squares, debated in classrooms. The common Kannada reader adored him. And through fine translations, like those by Uma Kulkarni into Marathi, he became beloved across India. Aavarana alone ran into 54 editions in a decade in Kannada — a testament to his popular appeal.

S. L. Bhyrappa lived as he wrote — simply, honestly, courageously. He left behind no heirs of privilege, no dynasty of entitlement, only the immortal children of his imagination.

How does one bid farewell to such a man? Perhaps by remembering and honouring his commitment to the truth and to the eternal civilisational values of Bharat. Bhyrappa is the rare Indian writer who gave us the courage to look at our past without blinkers, who reminded us that beauty and truth are not enemies but companions, who showed us that literature can be both lyrical and brutal, tender and fierce.

The writer is a freelance writer and newspaper columnist based in Pune.