Politics

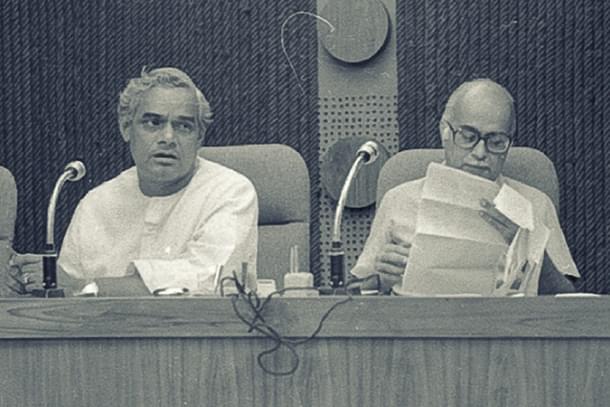

A Counter-Factual After Vajpayee’s Exit: Could Advani Have Ever Made It To PM?

R Jagannathan

Aug 17, 2018, 10:49 AM | Updated 10:48 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

Some time in 2012, Lal Krishna Advani, the eternal No 2 to Atal Bihari Vajpayee, said he had no regrets about never making it to the prime ministership. He said: “The party has given me so much in my life. Some people ask if you have any regrets about not becoming the prime minister. But the PM's post is nothing compared to what I have got from the country and party.”

This drew an unkind jibe from the irrepressible Lalu Prasad Yadav, who told a public meeting in Araria becoming PM wasn’t in his horoscope. (Yeh aapki kundli mein nahin hai).

With Vajpayee now passing away, it is worth ruminating over some counterfactuals. Could Advani have made it to PM, either on his own steam or as successor to his senior colleague in the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)?

The short answer is “maybe”, but the window of opportunity was narrow, between 2004-09, and that too only if Vajpayee had won the 2004 elections and his health had begun failing.

At any other time, he didn’t stand a chance. In 1996, when Advani scripted the BJP’s strong rise as the country’s single-largest party, the BJP was a political untouchable, and Advani would not have been an acceptable face as head of any coalition at that time. This is why he declared Vajpayee as the BJP’s prime ministerial candidate, and even Vajpayee was not fully acceptable in 1996. It was only after Deve Gowda’s coalition failed, followed by I K Gujral’s, and the BJP scripted another victory as single largest party in 1998, that even Vajpayee became acceptable. By 1999, and after the Kargil victory, of course, Advani’s chances eroded further, and became entirely dependent on Vajpayee anointing him PM at some future date when he was ready to hang up his boots.

His best chance would have come after 2004, assuming Vajpayee had won, and that too only if the latter’s failing health had forced him to anoint Advani as the next PM. We know now that Vajpayee’s health was worsening even before 2004, and after his defeat he practically withdrew from public life, and post-2009 he wasn’t even in a position to influence his party to give heed to Advani’s opinions.

In theory, Advani could have led the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) to victory in 2009, but the economic boom between 2003 and 2008 ensured that the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) got another term; in fact, if Vajpayee had won in 2004, Advani would surely have been PM some time between 2006 and 2009, either because Vajpayee’s health was ebbing, or because an NDA win in 2009 would have been probable based on solid economic performance. The UPA, despite mismanaging the economy, benefited from the high growth years of its first term, a boom attributable more to Vajpayee’s reforms and the general uptick in global economic growth.

In retrospect, it was clear that 2009 was not NDA’s best bet, and Advani ruined his chances forever despite being in good health by being the man to lead his party to an ignominious defeat.

Worse, he wasn’t even his party’s enthusiastic choice, for he had tainted himself in its eyes by calling Jinnah a “great man” when on a visit to Pakistan in 2005; the party could forgive a Vajpayee for visiting Minar-e-Pakistan in 1999 after his Lahore bus journey, but not perfidy at the hands of the man they considered a core Sanghi.

While the party still went with Advani as its prime ministerial candidate in 2009, having no other contenders, he was doomed to defeat. That defeat, and the rise of another man, Narendra Damodardas Modi as Gujarat’s rising star, sealed Advani’s chances, more so since the UPA had, by 2013-14 managed to mess up the economy and mired itself in several scams. By mid-2013, when Advani hesitated to endorse Modi as the PM candidate of the NDA, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh and party workers had already made the choice. Advani seemed like an old man desperately trying to grab the top job by hook or by crook. That effort to thwart Modi when the latter’s time had come was probably Advani’s worst miscalculation.

In retrospect, one can say that Vajpayee had everything Advani did not: wider political acceptability, great oratorical skills, the image of a great human being and consensus builder – and bloody good luck. This included his good fortune to have Advani as his loyal second-in-command, who had control of the party and its grassroots. Vajpayee climbed to power on Advani’s back.

Some men are born to rule; others merely to help them gain kingdom and rule.

Jagannathan is former Editorial Director, Swarajya. He tweets at @TheJaggi.