Columns

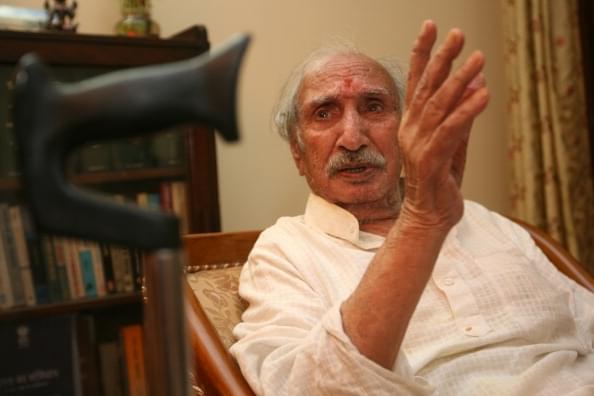

Balraj Madhok (1920-2016) Gave Us Definition Of Indianisation

Swarajya Staff

May 05, 2016, 06:24 PM | Updated 06:24 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

- Balraj Madhok, who passed away on 2 May, created one of the basic documents of cultural nationalism.

-

Madhok wanted to steer Jana Sangh as a liberal, capitalist party began to question what he considered the pronounced ‘leftward’ tilt in its economics.

Balraj Madhok was one of the founding members of Bharatiya Jan Sangh, the ideological precursor to India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party. He passed away in Delhi early this week (2, May). He was 96.

Madhok belonged to a generation of Hindutva leaders who strove to recover from the trauma of partition and the subsequent political treachery. A professor of history as well as an activist for Hindus and Sikhs in Jammu and Kashmir, any other person in his place would have become bitter and cynical. Yet, Madhok resisted and battled cynicism all his life.

Unfortunately, in the tectonics of Indian politics, uncompromising purists like him could seldom survive, even within his own party. He had worked with two great leaders of Jan Sangh – Shyam Prasad Mukherjee and Pandit Deendayal Upadhyaya, both of whom had tragic and mysterious ends.

As AB Vajpayee, with his charisma, systematically made Jan Sangh adapt to the new political ecosystem, Madhok found himself bitterly alienated. The bitterness ended in his expulsion from the party. These facts could never diminish his original contribution to the thought and evolution of Hindutva.

Kashmir Issue

As an activist, he gathered intelligence regarding the Pakistani military’s movements and passed it on to the Indian army during the notorious ‘tribal raiders’ carnage on Kashmir. He pleaded with Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru to help the Hindus and Sikhs who were stranded in what would soon become Pakistan-occupied Kashmir (PoK).

Here is an account by one of the witnesses

and a Hindu survivor of that tragedy:

On November 23, Prem Nath Dogra and Professor Balraj Madhok met Brigadier Paranjape, the Brigade Commander of the Indian Army in Jammu, and requested him to send reinforcements to Mirpur (a strategic place where more than one hundred thousand Hindus and Sikhs were held up during first Pakistani aggression over Kashmir). Paranjape shared their agony but expressed his helplessness because – as per instructions from the army generals – consultation with Sheikh Abdullah was mandatory in order to deploy Indian troops anywhere in Jammu and Kashmir. Paranjape also informed the delegation that Pandit Nehru would come to Srinagar on November 24 and they should meet him. On November 24, Pandit Dogra and Professor Madhok met Nehru and once again told him about the critical situation in Mirpur. They requested him to order immediate Indian troops reinforcement to the beleaguered Mirpur City. Professor Madhok was amazed at Pandit Nehru’s response – Pandit Nehru flew into a rage and yelled that they should talk to Sheikh Abdullah. Prof Madhok again told Pandit Nehru that Sheikh Abdullah was indifferent to the plight of the Jammu province and only Pandit Nehru could save the people of Mirpur. However, Pandit Nehru ignored all their entreaties and did not send any reinforcements to Mirpur.

On 24 November, Mirpur fell to Pakistani

artillery. The Hindus and Sikhs encountered a genocide that would “put to shame

worst orgies of rape and violence committed by the hordes of Genghis Khan and

Tamerlane,” according

to a survivor, Bal K Gupta.

Madhok was also a leader who prophetically

supported Dr Ambedkar’s idea of trifurcating Jammu and Kashmir. He supported

the Ladakh Buddhist Association’s demand for Union Territory status for the

region. In his statement to the press on 20 July 1973, he stated that Ladakh

should be made a Union Territory “in the interest of national security and

wider interests of the nation”.

It was also Madhok who brought to light Dr Ambedkar’s opposition to special privileges for Kashmir. When Jan Sangh, Swatantra Party and Congress (O) formed an alliance, they created a shadow cabinet in which Prof Madhok was the defense minister. During the Emergency, he was jailed under the Maintenance of Internal Security Act (MISA) for 18 months. His political career then came to an abrupt end.

Ideological Contribution

Madhok created one of the basic documents of cultural nationalism. Starting from the 1952 Jan Sangh resolution on ‘Indianisation’ to the 1969 resolution, he had worked on the concept in detail. None other than MC Chagla, a patriotic and progressive Muslim leader and jurist, delivered a speech in Rajya Sabha on ‘Indianisation’. He brought to the national conscience the works of another Indian Muslim intellectual Hamid Dalwai.

What is Indianisation? Madhok wrote: “All Indians, to whatever caste, creed, language, sex, sect or way of worship they may belong, have a common obligation towards this nation and common rights born out of those obligations. All those who look upon this vast country as their home as distinct from a hotel and cherish its culture, tradition and way of life are one people and one nation.” The ‘Indianness’, he said, should not be “determined by one’s colour, caste, language, way of worship or political party.”

A great activist, fighter and intellectual, though his movement did not use him to the full potential, he will always remain in our minds as a guiding light towards Indianisation. He defined it as “making every citizen of India a better Indian, a good patriot and a nationalist”.

Madhok was a strong votary of steering Jana Sangh as a liberal and capitalist party. He was a fierce opponent of Nehruvian state socialism. His tough position against the nationalisation of banks earned him the ire of the section of the party led by Vajpayee which advocated a more populist position as a means of political expansion. This made him a natural ally of Swatantra party. Madhok relentlessly worked for the merger of Jana Sangh and Swatantra and envisaged that such a combined formation would emerge as a well-defined ideological alternative to the ruling Congress establishment.

Madhok increasingly began to question what he considered the pronounced ‘leftward’ tilt of Jana Sangh in its economics. Indira Gandhi had unleashed a powerful wave of socialist sloganeering that had captured the nation’s imagination, and the Vajpayee-led section of Jana Sangh determined that a perception of pursuing pro-rich, capitalist policy will sound a death knell for Jana Sangh’s electoral prospects. Madhok’s advocacy of a strident Hindu Conservative position also did not synchronise well with the deft social engineering attempts mounted by RSS to broaden its social base.

However, Madhok could never win the trust of RSS in his effort to shape Jana Sangh in the Shyama Prasad Mukherjee mould – as a Hindu traditionalist party with a commitment to liberal economics. That Madhok, despite his aggressive Hindu nationalism, was not a typical pracharak from the cloistered world of Sangh, stood against him in intra-party battles. Madhok felt that RSS should provide operational autonomy for Jana Sangh to navigate its way through the political process. He lost the internal power struggle and was eventually expelled.

Madhok’s breakaway group hardly attracted any support. He turned a bitter man and began to indulge in wild conspiracy theories.