Politics

Gujarat Assembly Elections 2022 — Busting Myths And Narratives Around The Major Contenders

Venu Gopal Narayanan

Sep 18, 2022, 05:40 PM | Updated 05:40 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

While campaigns for the forthcoming Gujarat assembly elections have yet to start in earnest, spin doctors and narrative builders are already hard at work in trying to shift perceptions to their advantage.

Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal of the Aam Aadmi party (AAP) was in Ahmedabad this week. There was the usual promise of freebies to people who hadn’t asked for it, followed by a visit to the home of an autorickshaw driver for a meal.

It also included a mandatory, staged altercation with local police, as he attempted to breach his own security (with half a dozen cameras recording the revolutionary’s indignation in high definition, of course).

“I don’t want your security! Go give it to your CM,” Kejriwal fulminated boorishly. “You want to arrest me? BJP is going…AAP is coming.”

Now, if any other chief minister had spoken to a government servant in this deplorable manner, the press would have been calling for his resignation. But this is weary politics, Kejriwal-style, and a follow up to the media narrative that he and his party will make a splash in the Gujarat assembly elections (see here for more on such efforts).

The actual opposition in Gujarat, the Congress, is unfortunately off duty at present. Its national leaders are busy trying to corral the identity vote through a yatra in Kerala.

Plus, the availability of Jignesh Mevani, the party’s state vice president, is in doubt since he has been sentenced to six months imprisonment in a 2016 rioting case.

So, what is the ground position?

Will the AAP have a grand opening? Is it really going to replace the Congress?

Is 2022 going to be a close-run affair like 2017 when the Congress played three flagrant caste cards to give the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) a scare?

The truth, as our analysis reveals, is that there is a yawning gap between perception management and reality.

One, the AAP will be hard-pressed to win even a handful of seats. If on the outside chance that it actually does so, the wins will come at the cost of the Congress.

Two, the few advantages the Congress gained in 2017 have since been squandered for a variety of reasons. The momentum has swung back to the BJP. (See here for a detailed assessment of how the political situation in Gujarat has shifted to the BJP’s advantage once again.)

Three, a study of the 2017 victory margins in Gujarat shows that it was not a close-run affair. On the contrary, the Congress never had a chance of upsetting the BJP.

This is a startling insight because the popular refrain since 2017 is that the Congress might just have wrested the mandate with a little bit of luck.

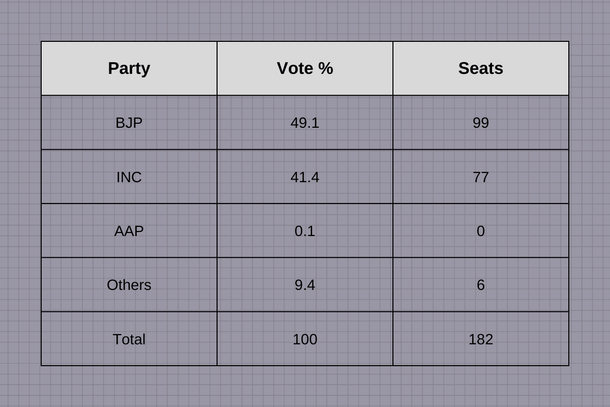

Here are the results of the 2017 Gujarat assembly elections:

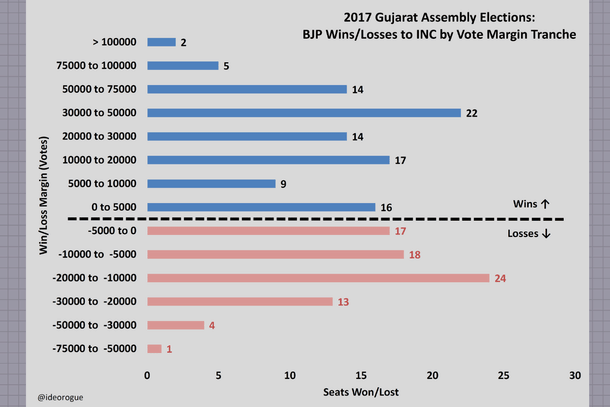

And here’s the proof to rebut the spinmeisters’ spiel:

Chart 1 segregates constituency wins by vote margin tranches. BJP wins are represented by blue bars and Congress wins by pale red.

A margin of under 5,000 votes is considered an extremely tight contest since that is less than 2-3 per cent of the total vote share. A minor swing of 1 per cent can change outcomes.

Similarly, any margin between 5,000 and 20,000 is categorised as a close contest, and anything above it as a solid win.

The win/loss margin was less than 5,000 votes in 33 of the 182 seats, meaning that the results could have gone either way. Both the Congress and the BJP shared wins equally in this tranche. The inference is that this is where the Congress’ caste ploy hurt the BJP the most.

On the other hand, we see that 77 per cent of Congress’ 77 wins were by a margin of under 20,000 votes, whereas 58 per cent of the BJP’s win margins were over 20,000.

The first inference is that while the Congress did dent the BJP in 2017, it did nothing to impact the overall outcome.

The second inference is that these Congress wins are, in fact, more tenuous than we realise.

The third inference is that if the BJP recovers even 1-2 per cent of the vote share they lost in 2017 (by this writer’s assessment, they have), then many of these Congress wins would get promptly converted into BJP wins in 2022.

Why do we say this and how can we quantify it?

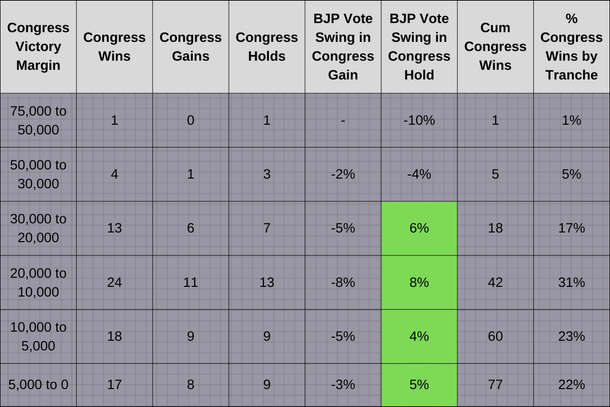

Table 2 shows that, of its 77 wins in 2017, the Congress gained 35 seats and held 42 (for comparison, the BJP held 81 and gained 18 — another mark of its inherent resilience in Gujarat).

But, curiously, we see that the BJP improved its performance in 38 of the Congress’ 42 holds (positive vote swings to the BJP are shaded in green) and the Congress retained 31 of these 38 seats only by slender margins.

Similarly, the Congress won roughly half its seats — 35 of 77 — with a margin of less than 10,000 votes. In 18 of these, which were Congress holds, the BJP is gaining on them inexorably.

In 17 seats, the BJP are just 1-2 per cent behind (0 to 5,000 tranche), and in eight of those, which are Congress gains, the BJP lost just 3 per cent vote share in 2017.

These statistics underscore the actual, subliminal fragility of the Congress’ mixed performance in 2017 and indicate that it was a one-off affair, with an extremely low probability of a repeat in 2022 — not least because the three caste factors which the Congress employed in 2017 have been sequentially neutralised by the BJP.

Hardik Patel and Alpesh Thakore, who created a flutter among the Patels and the other backward classes (OBCs), have joined the BJP. And the unpopularity of Mevani, who was deployed by the Congress to stoke discord among the Dalits, is now at Medha Patkar depths in Gujarat after his active, open involvement with Naxals during the 2018 violence at Bhima Koregaon, Maharashtra.

Now, what would be the effect if the AAP were to enter this scenario?

It is axiomatic that the first votes to go to the AAP would be from the Congress since that is where the anti-BJP vote rests in bulk.

If that happens, the inherent brittleness of the Congress will be exposed because even a 1-2 per cent shift of votes from them to the AAP would hand a number of seats to the BJP.

On the other hand, even if the AAP cuts into the BJP’s vote base, and by far more than it manages with the Congress, the impact on outcomes would still be muted since that bulk of the BJP’s victories are solid which can withstand significant erosions.

Thus, in conclusion, and ignoring the efforts of narrative builders, this is the situation in Gujarat today:

The BJP is poised to do much better than it did in 2017 and its performance will only improve with each vote that the AAP cuts.

Either way, it is the Congress which will have to bear the brunt of this inevitable reality.

Venu Gopal Narayanan is an independent upstream petroleum consultant who focuses on energy, geopolitics, current affairs and electoral arithmetic. He tweets at @ideorogue.